Dr. Jerry Kolins

Dr. Kolins presents, “On My Obsession with Michigan Football.”

I often ask myself why I care about the Michigan football program. I never played the game. In high school, I wanted to letter in a sport – any sport. I tried out for baseball. I didn’t make it. I made the varsity handball team in the off-season. Boy, was I excited! What I didn’t know was that the really good players never show up for the off-season, because there were no competitive games then. I practiced and showed up figuring it would improve my chances of lettering in the Spring. But there was no place for me when the season started. I was not good enough. These guys who only show up in the Spring were the best I ever saw. I never played again.

When I was an undergraduate student at Michigan, I attended two Michigan football games. I remember Michigan playing Michigan State in 1967. My roommate said I had to go to this game if I ever wanted to say I graduated from Michigan. Michigan lost before half-time. And that’s when I left the stadium. In my junior year, I watched Michigan lose to Purdue 22-21. Bob Griese, who quarterbacked Purdue, later quarterbacked the Miami Dolphins to two consecutive Super Bowl championships. Brian Griese, who quarterbacked Michigan to a national championship in 1997, is Bob Griese’s son. At the 1966 Purdue game, Michigan had the ball in Purdue territory with only a few seconds remaining. A 35-yard field goal would win it. The ball did not reach the end zone. I graduated and went to medical school – just like I always wanted.

After I left Michigan, I got consumed by the game. Since I attended medical school at Wayne State University in Detroit, it was easy to return to Ann Arbor. During my freshman year of medical school, 1968, Michigan played Ohio State in Columbus. I listened on the radio because not much college football was televised then, and of course, there was no cable TV nor Big Ten Network. Ohio State was No. 1 in the country in 1968, but at halftime, the score was close, 21-14 in Ohio State’s favor. The Buckeyes dominated the second half, and with less than a minute remaining in the game, scored a touchdown that pushed their lead to 48-14.

Then, even though up by 34 points, OSU went for a 2-point conversion and made it! The final score was 50-14. For a very short time, I wondered why Woody Hayes went for two with only seconds left in the game. I didn’t wonder for long because, as legend has it, that was the first question the press asked Woody after the game. Woody said he went for two because the referees would not let him go for three. This was entertaining. There is something going on between Michigan and Ohio State that intrigued me.

During my sophomore year in medical school, in 1969, I went to two Michigan football games. I watched Michigan lose to Michigan State (MSU) in East Lansing. I still remember an MSU kickoff to one of Michigan’s most accomplished running backs. He caught the ball on the 1-foot line and took a step back into the end zone and placed his knee on the ground. That is called a safety. Michigan State got 2 points and the ball back. We lost a game that we should have won. That made the Michigan State rivalry even more exciting. And it was not the last time Michigan lost to an inferior Michigan State team. Even Michigan State fans do not believe they won the 2015 contest.

We need a brief sidebar. In 2018, John Bacon, the author of several New York Times best sellers, explained the difference between Michigan vs. Notre Dame football, Michigan vs. Ohio State football, and Michigan vs. Michigan State football. In a Michigan vs. Notre Dame game, the players and the fans respect each other. In the Michigan vs. Ohio State game, the players respect each other, and the fans hate each other.

In the Michigan vs. Michigan State game, the fans and the players hate each other. That summary somehow captures the cultures of these rivalries. Yet Michigan will be the first to admit that Michigan State is the little brother compared to the unrivaled competition between Michigan and Ohio State. This competition was always intense, but it reached new levels thanks to Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler.

Why the hell would I care?

My answer may not be completely satisfying, but it is an attempt to understand myself. Let me explain with help from Edward O. Wilson. He is a Harvard biologist who has written Pulitzer Prize-winning books that attempt to answer these difficult questions: Is there a judgmental God? What is the meaning of human existence? Wilson answers the first question in his book, Consilience. This is no easy read. He writes a chapter in which he explains why there absolutely must be a judgmental God. It is a convincing chapter. The subsequent chapter outlines the argument against the existence of a judgmental God. That argument is irrefutable. Yet Wilson welcomed the reader to challenge his position. In his book, The Meaning of Human Existence , Wilson makes his position clear that humans need a society in order to survive, which is unusual among mammals.

Religion is not a prerequisite for society, though most of us don’t accept this.

What does this have to do with Michigan football?

Humans need a structured society; we need to belong to a group. If you believe in a judgmental God, you have a religion to bring you together. If you cherish your immediate family, they may provide the sense of belonging our genetic material demands. Your professional career may also provide this required sense of belonging.

What happens to those who believe the universe can be explained without conjuring up a God? What happens to those who feel neither family nor profession fills the void that DNA mandates?

Michigan football is my religion. As a religion, Michigan football provides many levels of satisfaction. When I go to Michigan Stadium, I sit with over 100,000 folks who I don’t know. And I like that. Actually, I prefer that. But we all have something in common. We feel connected to the University of Michigan through the football team. The team brings us together on Saturday the same way religion brings the masses to church on Sunday. And we are not really 100,000 people watching the game. We are about 25,000 groups of three to five folks who look forward to seeing each other six or seven times a year for life’s renewal. We will even gift to these otherwise strangers our personal and precious team souvenirs as we near the end of our life.

Roy sat next to me in Section 41 for years. He was a World War II veteran. He knew my love for Michigan and its football team. One day he gave me a signed photo of Tom Harmon, Michigan’s first Heisman Trophy winner, and his ticket to the 1930 Michigan vs. Illinois football game. I have them both framed and hanging in my Ann Arbor condo. That Michigan vs. Illinois ticket cost three dollars in 1930. Today the ticket would be more than twenty times that. But why would Roy give this to me? He knew I would protect his cherished, precious mementos. They needed protection, and I could do it. Perhaps the religious among us would call these relics.

Can our DNA control us the way I describe above? I don’t know. But I became a believer in 1969. The year after Woody Hayes went for two because they would not let him go for three, Michigan played Ohio State at home. It was November 22, 1969. I was there in the end zone seats. OSU was No. 1 in the country and had been since September 1968. Another OSU victory was predicted, but Michigan was not to be denied. At halftime, the score was Michigan 24, Ohio State 12. During the second half of the game, neither team scored a point. The Mets were not the only miracle in 1969. And I found a place to belong.

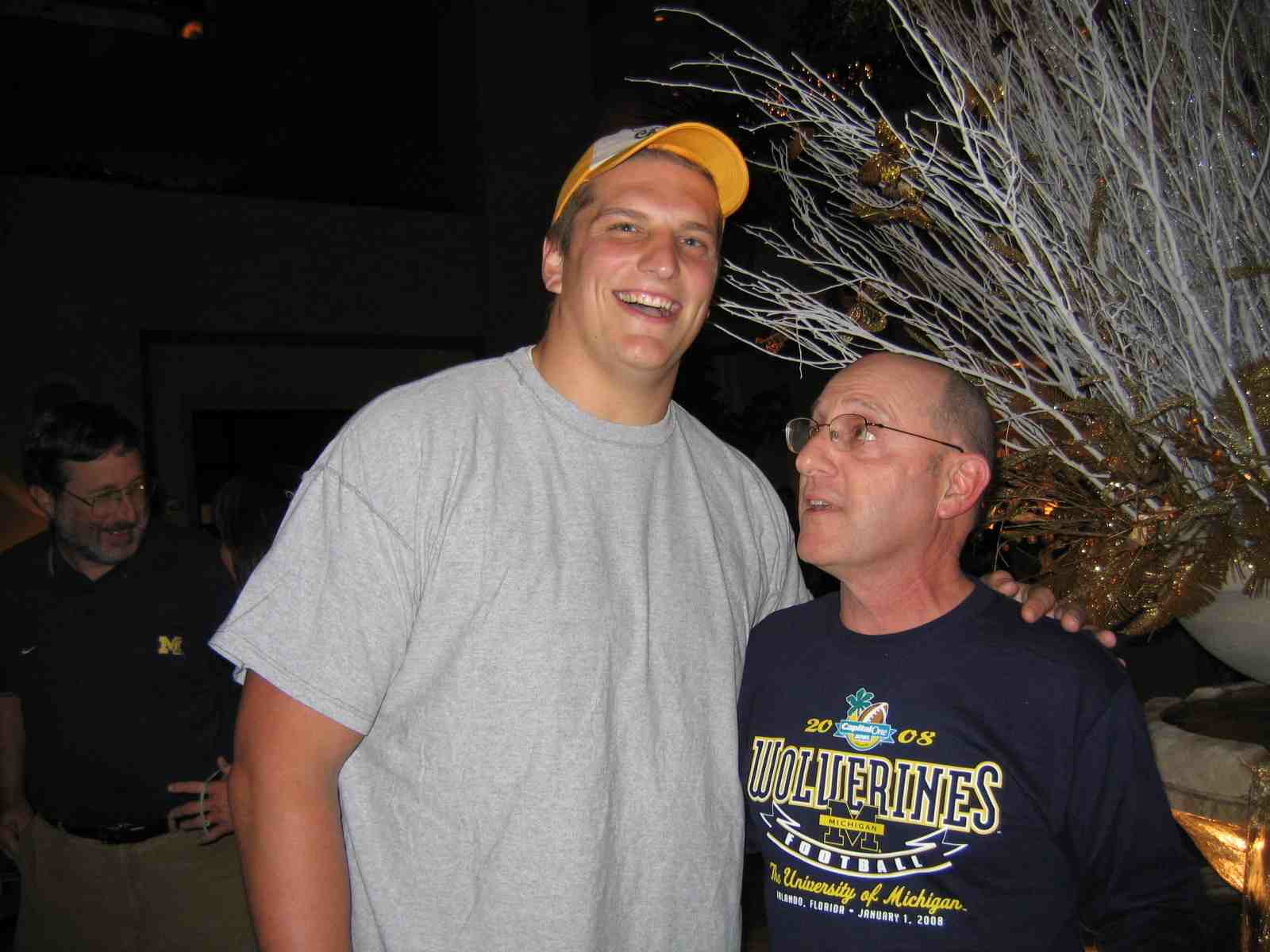

Mini Epilogue: I have lived in La Jolla, California, and have been a Michigan football season ticket holder since 1977. Between 1977 and 1997 (the year Michigan won the national championship), I attended up to three games a year. Since 2016, I have leased a suite over the freshman section. I haven’t missed a home game since. And United Airlines really appreciates that!

Footnote: From The Meaning of Human Existence by Edward O. Wilson:

“All things being equal (fortunately things are seldom equal, not exactly), people prefer to be with others who look like them, speak the same dialect, and hold the same beliefs. An amplification of this evidently inborn predisposition leads with frightening ease to racism and religious bigotry. Then, also with frightening ease, good people do bad things. I know this truth from experience, having grown up in the Deep South during the 1930s and 1940s.

“It might be supposed that the human condition is so distinctive and came so late in the history of life on Earth as to suggest the hand of a divine creator. Yet, as I’ve stressed, in a critical sense the human achievement was not unique at all. Biologists have identified at the time of this writing twenty evolutionary lines in the modern-world fauna that attained advanced social life based on some degree of altruistic division of labor. Most arose in the insects. Several were independent origins in marine shrimp, and three appeared among the mammals – that is, in two African mole rats, and us. All reached this level through the same narrow gateway: solitary individuals, or mated pairs, or small groups of individuals built nests and foraged from the nest for food with which they progressively raised their offspring to maturity.”

“Probably at this point, during the habiline period, a conflict ensued between individual-level selection, with individuals competing with other individuals in the same group, on the one side, and group-level selection, with competition among groups, on the other. The latter force promoted altruism and cooperation among all the group members. It led to innate group-wide morality and a sense of conscience and honor. The competition between the two forces can be succinctly expressed as follows: Within groups selfish individuals beat altruistic individuals, but groups of altruists beat groups of selfish individuals. Or, risking oversimplification, individual selection promoted sin, while group selection promoted virtue.”

JERRY KOLINS, BS ’68, is a medical director of laboratories at Palomar Health in Escondido, CA. As you are now aware, he is a passionate fan of the Michigan Wolverines.