Degrees of Access

•

The University of Michigan is a global leader in higher education, known for excellence in academics, research, and athletics. With 19 undergraduate schools and colleges, a medical and law school, Big 10 sports, and countless additional programs and opportunities for students, faculty, and staff, U-M is consistently ranked as a top university in the country.

However, there is one area where the University falls short of its aspirations: racial diversity among its student body. It’s an issue U-M has grappled with for decades.

At one time, U-M used race-conscious admissions policies, a common practice among colleges and universities that uses race as a factor among many when considering applicants. U-M’s policy was challenged all the way to the Supreme Court. After that legal case, the practice was banned in the state of Michigan when voters amended the state’s constitution.

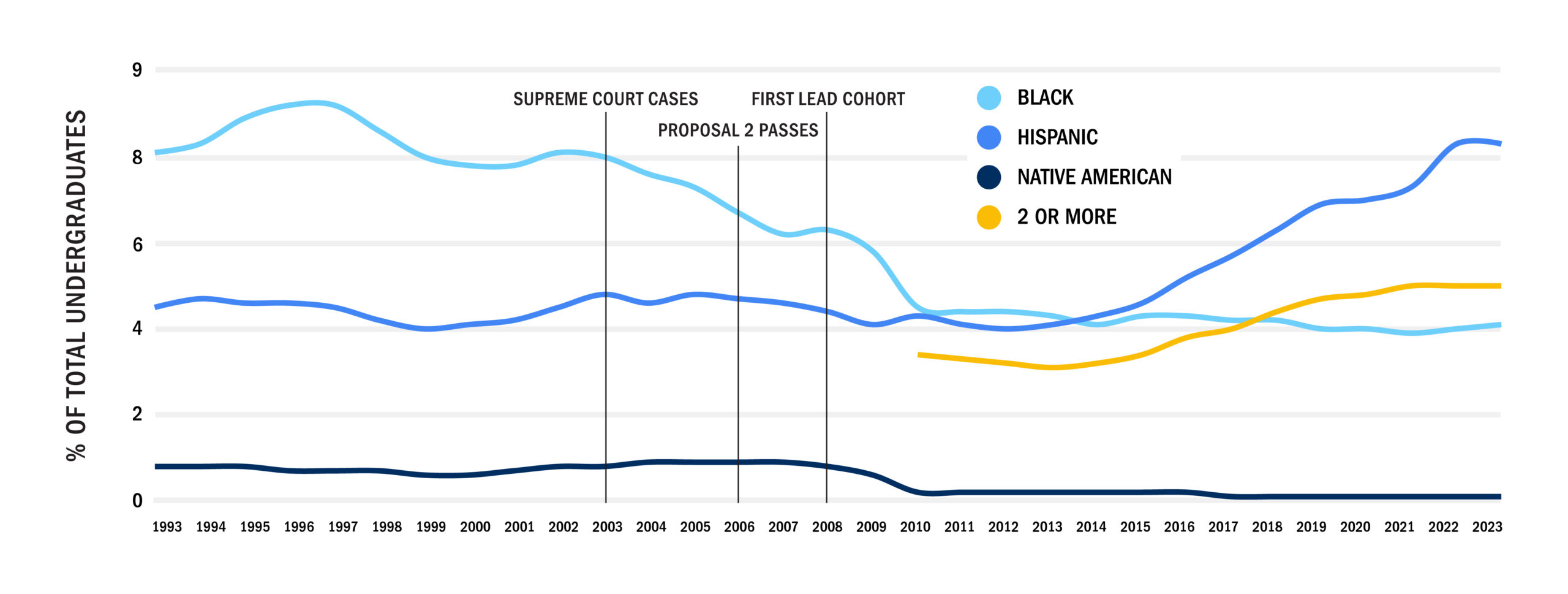

In the years that followed, the number of underrepresented minority students on the Ann Arbor campus plummeted, and the University has had to rethink how it recruits and uses outreach programs in an effort to increase racial diversity on campus.

The topic of affirmative action is back in the news after the Supreme Court’s landmark decision to outlaw the practice of race-conscious admissions policies in higher education. As institutions across the country look to find ways to foster diverse student populations and inclusive campus climates in an era devoid of affirmative action, U-M has been working toward a solution for nearly 20 years.

What is Affirmative Action?

Affirmative action is the practice or policy of favoring individuals belonging to groups regarded as disadvantaged or subject to discrimination.

The practice of affirmative action stemmed from a 1965 executive order signed by President Lyndon Johnson, which prohibited federal contractors and federally-assisted construction contractors and subcontractors from discriminating in employment decisions on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It also said that if there was underrepresentation, they needed to take “affirmative action” to address the underrepresentation.

The policy has been deeply controversial and, at times, very unpopular. A Pew Research poll conducted ahead of the Supreme Court’s decision in June found that half of Americans disapproved of selective colleges considering race in admissions cases while 33 percent approved of the policy. The rest were undecided. The poll showed that 29 percent of white, 37 percent of Asian, 39 percent of Hispanic, and 47 percent of Black respondents favored it. Many were undecided.

In the same poll, a third of all respondents said they believed students admitted due to affirmative action policies were less qualified than other students, a common misinterpretation of race-conscious admissions programs. Pew says polls surrounding affirmative action are highly sensitive to how the questions are asked, meaning many respondents may misunderstand what affirmative action actually means.

Affirmative action doesn’t mean under- or unqualified people are getting unearned advantage. It actually means recognizing people who have actually been able to do a lot more with less.

-- Tabbye Chavous

In college admissions, affirmative action policies allowed universities to increase the admission rate of minority students, specifically Black, Hispanic, and Native American students who have experienced unequal access to education due to centuries of systemic discrimination that affects public school funding, access to resources, generational wealth, and more.

It helped ensure underrepresented minority students were offered equitable access to higher education at elite institutions, which prepare students to become leaders, innovators, and entrepreneurs in every industry.

“Affirmative action doesn’t mean under- or unqualified people are getting unearned advantage,” says Tabbye Chavous, U-M’s vice provost for equity and inclusion, and the University’s chief diversity officer. “It actually means recognizing people who have actually been able to do a lot more with less.”

Challenging Admissions Practices

The landmark 2023 cases that overturned affirmative action in college admissions weren’t the first to grace the Supreme Court’s docket. In 1978, the University of California’s demographic quota-based system was ruled unconstitutional, however, the court ruled that colleges and universities had a compelling interest in the educational benefits of a diverse student body, allowing race-conscious admissions to be used as long as race was one factor among many considered.

That was the law of the land when students who were not admitted to U-M challenged the University’s policies in two separate cases that rose to the Supreme Court in 2003.

In 1997, Barbara Grutter, a white Michigan resident, alleged that she was rejected from Michigan Law because it used race as a “predominant” factor, giving applicants belonging to certain minority groups a significantly greater chance of admission than students with similar credentials from “disfavored” racial groups.

In the other case, Jennifer Gratz and Patrick Hamacher, both white Michigan residents, were denied admission to LSA in 1995 and 1997, respectively, though LSA determined they were reasonably qualified for admission.

Both cases alleged racial discrimination under the 14th Amendment.

Decided on the same day, the Supreme Court ruled that the law school’s actions were constitutional, as long as race was considered one factor among many in a holistic admissions process. With the same reasoning, the points-based process used in U-M’s undergraduate admissions was ruled unconstitutional as it was too narrowly focused and offered a significant bonus for race alone, without a compelling interest to justify the use of race.

After these cases, the University adopted similar undergraduate admissions practices as the law school to comply with the Supreme Court’s ruling. But this was far from the end of the discussion as the issue began to rise to the ballot in Michigan.

The Inception of LEAD

When Proposal 2 passed in 2006 in Michigan, as a separate nonprofit organization from the University, Alumni Association leaders wanted to find a way to support diversity on campus.

“I don’t think we expected it to pass. But we just felt like somebody had to — needed to — try to do something,” says Steve Grafton, former president and CEO of the Alumni Association. “And the fact that we were not a state government entity, but we were close enough to the University, cared enough about the University, and part of our purpose is to support the University. And so we felt like if there was something that we could do, we should try to do it.”

The Alumni Association’s board of alumni volunteers determined the best way to help was to incentivize enrollment and encourage retention of underrepresented minority students or students underrepresented in certain academic fields, such as women in physics or men in nursing. It would give alumni and others a way to partner with the Alumni Association in support of a diverse student population, and was set up to be similar in concept to club scholarships which encourage geographical diversity.

LEAD was designed to intervene not in the admissions process, but in the students’ decision process. After they were admitted to U-M but before they decided to attend the University, applicants received an offer to apply for a merit-based LEAD scholarship. To become a LEAD Scholar, the students must embody leadership, excellence, achievement, and diversity.

“These students are as important to the success of the University as anybody else. We need to really try to recruit them to come here. And so that was the approach that we decided to take. Our board never hesitated in their support for it. It was immediate,” Grafton says.

Grafton compares LEAD with athletic recruiting and scholarships — student-athletes still have to be accepted to U-M based on their academic rigor.

"What I’ve always talked about is no more ‘underrepresentation.’ That’s the ideal state."

-- Steve Grafton

It took time to develop the program and verify the legality of the process, but the LEAD Scholars program accepted its first class in the fall of 2008 with 22 Scholars.

Once on campus, LEAD would offer a community with unique opportunities for engagement and development, with a goal of retaining students through a sense of community and belonging. With scholarship funding as a recruiting tool and community as retention, the LEAD Scholars program helps high-achieving, already-accepted students choose U-M over other prestigious institutions.

In the fall of 2023, LEAD welcomed its 16th and largest cohort yet with 80 new Scholars at U-M, totaling 758 students who have been part of the LEAD community. More than 1,100 first-year students applied for the program.

Though LEAD is just one of many programs that help support diversity on campus, leaders like Grafton imagine the day that they’re no longer necessary.

“What I’ve always talked about is no more ‘underrepresentation.’ That’s the ideal state,” Grafton says. “If we could reach a point where we don’t have to think about creating diversity because it just is. The diversity that is who we are as people is the diversity that is who our [students] are at Michigan. That’s the vision.”

LEAD Scholars Program Myths + Facts

MYTH: LEAD is an affirmative action program.

FACT: The Alumni Association and the LEAD program have no influence over admission decisions. Today, the program is targeted toward underrepresented minority students already admitted to the University.

MYTH: LEAD helps unqualified students attend U-M.

FACT: Students who apply for a LEAD scholarship have already been admitted to U-M on their own merit. LEAD helps incentivize enrollment of underrepresented minority students at U-M with financial and community support.

MYTH: LEAD is a way for the University to work around Proposal 2.

FACT: The Alumni Association is a nonprofit organization separate from the University of Michigan. LEAD is entirely funded by donors and administered by the Alumni Association and it is not financially supported by U-M.

MYTH: LEAD scholarships are need-based.

FACT: LEAD is a merit-based program that is highly competitive. More than 1,100 students applied to be part of the 2023 Cohort with 80 students joining the program as first-year students this fall.

MYTH: LEAD is just a scholarship.

FACT: Beyond scholarships, LEAD offers a community experience that provides a sense of belonging for Scholars. The program also offers opportunities for networking with alumni, career guidance, mentorship, and study groups.

To learn more about the LEAD Scholars program or to donate, visit alumni.umich.edu/lead.

Other Strategies

The University believes strongly in the value of having a diverse student body and, without being able to use race or gender as a factor among many in its admissions policies, has worked to find new ways to recruit underrepresented minority students to campus.

Chavous says proactive and targeted engagement is important.

“Some of the things that we can do legally are to look at school districts and communities that have been historically underserved,” she says. “So there’s nothing to prohibit us from focusing on areas based on demographic features related to socioeconomic status and resources.”

One particular program that has yielded results is Wolverine Pathways. The program provides free college preparatory enrichment and guidance for seventh through 12th-grade students in the Michigan communities of Detroit, Southfield, Ypsilanti, and Grand Rapids.

“The Wolverine Pathways program has significantly impacted the in-state yield of underrepresented minority students, with a specific impact for Black students,” Chavous says. “In a little over five year period, that program came to account for 20 percent of the incoming Black students at Michigan. And that’s just one program and the goal is to have that program be a model so that could be scaled.”

The University’s Center for Educational Outreach has also been key. The initiative was born in the wake of Proposal 2. It aims to expand U-M’s impact in educational outreach by strengthening collaboration and coordination between the U-M community and K-12 schools in Michigan.

Both of those programs target in-state students, but about half of the undergraduate students come from outside of Michigan. Chavous says there’s still good work to be done with out-of-state students, and that includes tapping the alumni network and being sure the message is clear that U-M is welcoming and supportive of all students.

“We are able to show that we’re creating community spaces for different student communities, different cultural communities on campus,” Chavous says. “Places like the Trotter Multicultural Center, which is both a visible, physical symbol … but also infusing that space with programming and staff and peer engagement opportunities that are appealing to students.”

Despite the work, U-M’s student body remains less diverse than it was when the University was able to consider race as a factor among many in admissions. The Black student population, for instance, has been around 4 to 4.5 percent for several years, which is about half of what it was 20 years ago. The Black Student Union has voiced concern about the numbers.

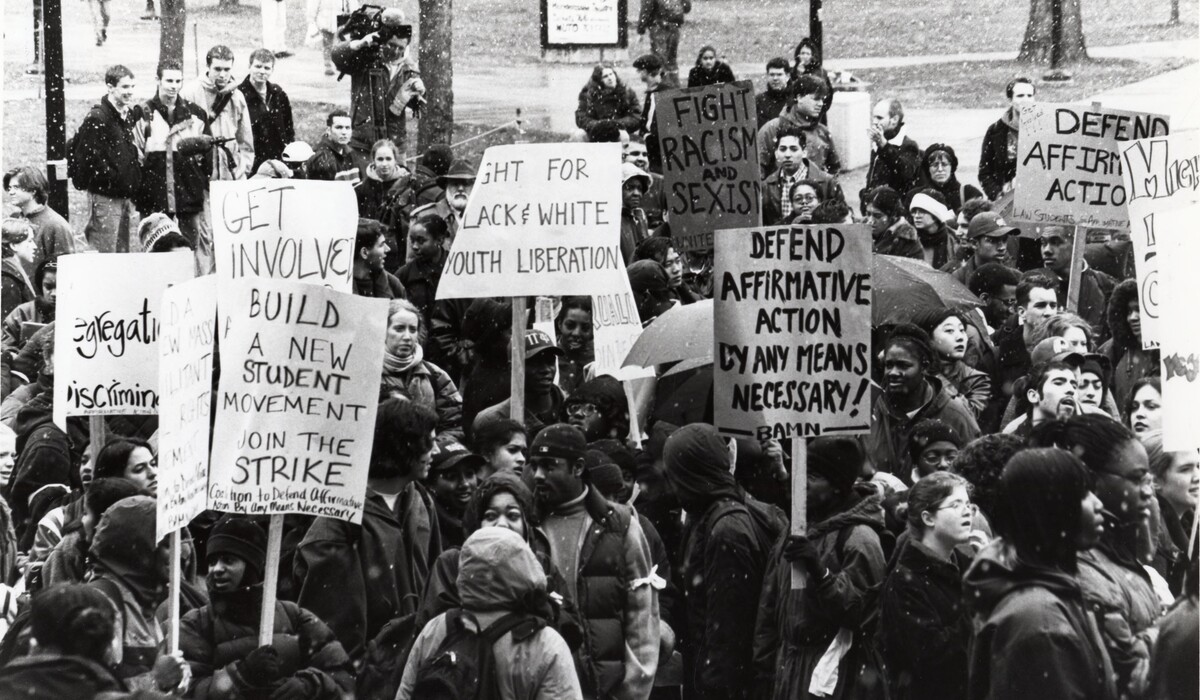

Last fall, the group held a rally on the Diag and outlined a platform titled, “More Than Four.” They have asked the University to increase Black student enrollment, combat anti-Blackness, increase efforts in K-12 education, and change diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts.

Black students fighting for an increased presence on campus isn’t new: it’s been the focus of sit-ins, protests, and rallies since at least the 1960s with the Black Action Movement. Groups have long fought for the student population at U-M to reflect the population of the state of Michigan where 12.4 percent of residents identify as Black.

“I think it’s achievable because we’ve made progress. And not only are we making progress, but we’re not satisfied with that progress,” Chavous says about hitting that mark in the future. “We’re looking at practices that have led to progress and ones that have been less successful. And our institution and our leadership is doubling down on the things that are making an impact.”

Supreme Court Ruling

The fight over race-conscious admissions practices in the U.S. came to an end in June. The Supreme Court banned the policy in higher education in a 6-3 vote, ruling that the practice violated the 14th Amendment.

At the heart of the issue were two cases, one filed against Harvard University and the other against the University of North Carolina. In the Harvard case, the plaintiffs argued that Asian students were being discriminated against in its admissions process and the population of Asian students on campus would be higher if race wasn’t used as a factor.

“Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his majority opinion. “We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and will not do so today.”

While outlawing the consideration of race in admissions, Roberts also wrote that universities can consider an applicant’s discussion of how race has affected their life in personal essays, “be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.”

In his concurring opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that the solution to our nation’s racial policies cannot come from policies grounded in affirmative action or some other concept of equity.

“Racialism simply cannot be undone by different or more racialism,” he wrote.

Liberal justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote dissenting opinions, with Sotomayor saying the ruling rolled back decades of precedent and progress and Brown writing that gulf-sized race-based gaps exist with respect to the health, wealth, and well-being of Americans.

“With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, today, the majority pulls the ripcord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal fiat,” Jackson wrote. “But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life.”

What Comes Next?

High school seniors are currently working on their applications for early decision and college admissions officials around the country have revamped policies to comply with the Supreme Court’s ruling on race-conscious policies. How the court’s decision will ultimately impact the racial makeup of elite colleges is unknown. But experts say history might be a guide.

Before the ruling, nine states — Arizona, California, Florida, Idaho, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Washington — had some form of an affirmative action ban in higher education in place.

During a webinar on the topic with U-M’s Ford School of Public Policy and the Center for Racial Justice, professor Mara Ostfled said the data was clear on the outcome of those policies.

“We have an abundance of data that this harms students of color,” she says about a ban on race-conscious admissions policies. “From the application stage in the context of admissions and the context of acceptance rates. We have a lot of evidence that this will be a hurdle.”

The goal is to make sure we’re supporting access to higher education, which means selective institutions all over the country, not just Michigan. Because that’s what’s going to impact our society.

-- Tabbye Chavous

The company that operates the common application process announced that it is allowing colleges and universities to suppress self-disclosed race and ethnicity information from the data they see from a student. The Supreme Court ruling doesn’t prohibit colleges and universities from collecting the information; it prohibits them from using it in making admissions decisions, but some institutions will likely be overly cautious and risk-averse, Chavous says, and take that option.

Both Ostfeld and Chavous expressed concern that many colleges and universities won’t collect race data.

“If you aren’t measuring race, you can’t show there are ongoing disparities,” Ostfeld says. “I would be very troubled if race wasn’t included on applications just for the purpose of documenting trends.”

Because many legal experts expected the conservative-leaning court to overturn affirmative action, Chavous says many institutions have been preparing for that outcome.

“I’ve been in this position a year, and I probably get a call a week from an institution that wants to know something about the ways that we addressed the ban on consideration of race and gender in college admissions,” Chavous says. “So I think there was an eagerness to prepare.”

U-M was proactive in those discussions, sharing strategies that both complied with the law and also helped increase the diversity of the student body.

“The goal is to make sure we’re supporting access to higher education, which means selective institutions all over the country, not just Michigan,” Chavous says. “Because that’s what’s going to impact our society.”

DEI 2.0

The University of Michigan recently concluded its first five-year strategic plan for diversity, equity, and inclusion. This fall, it is launching the second phase of the effort: DEI 2.0.

The program takes a bottom-up approach, where departments, units, and colleges develop their own internal efforts, not mandated by the University’s top administrators. The aim is to enhance diversity, increase the inclusiveness of the academic community, and promote greater equity across campus.

“The mantra for DEI 2.0 has been to be more strategic, more focused, [and] doubling down on things that are successful and effective while also being bold and innovative,” says Tabbye Chavous, U-M’s vice provost for equity and inclusion, and chief diversity officer.

Chavous says DEI 2.0 will be focused on the three Ps: people, process, and products.

The people part looks at the efforts to recruit, retain, and develop a diverse community at the University. Processes are the things that relate to creating an equitable and inclusive environment, such as how the University improves the climate and supports a greater sense of belonging. And products are what innovations are being created related to diversity, equity, and inclusion such as new courses and new modes of inclusive teaching.

“Our units did a great job of analyzing their own outcomes from 1.0 and determining which ones showed the most success and which ones they wanted to continue to invest in,” Chavous says.

As an example, the curriculum in DEI 2.0 will go beyond awareness and on to building skills. Leader-specific programming seeks to develop the skills of leaders to prevent workplace issues and retaliation, disrupt bias, engage in anti-racism dialogue, and build psychological safety in the workplace.

DEI 2.0 kicks off Oct. 9.

KATHERINE FIORILLO is the editor of the Michigan Alum.

JEREMY CARROLL is the content strategist for the Alumni Association of the University of Michigan.