In June 2013, the state-appointed emergency manager in Flint, Michigan, decided to switch the city’s water source from the Detroit water system to the corrosive Flint River. As the world now knows, this fateful decision, carried out in April 2014, would have an impact on the city’s residents for years, if not lifetimes, to come.

Now, a pair of U-M alumnae share the story of this American tragedy in two books due out this summer: “What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City” by Mona Hanna-Attisha, ’98, MPH’08, and “The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy” by Anna Clark, ’03.

The authors tell of residents who immediately noticed that something was wrong—discolored tap water smelled and tasted bad. They tell of Virginia Tech water quality expert Marc Edwards, who presented evidence at a September 2015 press conference that Flint had elevated levels of lead in its water, some so contaminated it was deemed toxic waste. They also tell of government officials who insufficiently treated the Flint River water, ignored the pleas of citizens who suspected lead contamination, and failed to act until much damage had been done.

Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician at Flint’s Hurley Medical Center, also shares how her research on patients’ blood lead levels provided the crucial evidence that the lead-laced water was actually poisoning children. And she tells why she decided to risk her reputation and career in the service of her patients.

An award-winning journalist and U-M Knight-Wallace Fellow, Clark was on the ground early in the crisis, trying to make sense of what was happening and why. Her book is one of the first comprehensive accounts of the scandal. A longtime resident of Detroit, Clark spent years living through and reporting on issues that blighted both Flint and Detroit, including emergency management and racial and economic injustice.

Leana Hosea, the inaugural media fellow in U-M’s School of Environment and Sustainability, met the two women in Flint recently to discuss their experiences and their new books. En route to a cafe, Hanna-Attisha and Clark pointed out signs of regeneration in Flint, clearly fond of the city they serve and willing it to recover.

HOSEA: Mona, I wanted to ask about the title of your book, which derives from the quote “The eyes don’t see what the mind doesn’t know.” What is the meaning of that quote in light of the Flint water crisis?

HANNA-ATTISHA: First of all, very literally, your eyes do not see lead in water; itís invisible. You donít see the consequences of lead exposure for years, if not decades. I have taken care of countless kids with lead poisoning, but never did I think that water could be a source of exposure. So I missed many diagnoses because my eyes never saw what my mind never knew.

HOSEA: Anna, how does that idea relate to what you felt when you came to Flint on your first water story, before the scandal had really been uncovered?

CLARK: I had done a number of stories about Flint on different issues before the water crisis. But my first story about the water explicitly was in the fall of 2015 for the Columbia Journalism Review. When I look back on it now, I can see myself learning as I go. There is a line in the article that suggested it was over, which wasn’t true, of course. But I didn’t understand the extent of the crisis at that time. Back then, the community thought the decision to switch back to Detroit water from the Flint River was such a big win for the city, I couldn’t see how it was going to escalate from there. But I kept reporting, learning, and listening.

HOSEA: And when the authorities are telling you something completely different, it’s difficult to decipher the truth. What kind of obstacles did you face from the authorities, before they admitted there was a problem with the water?

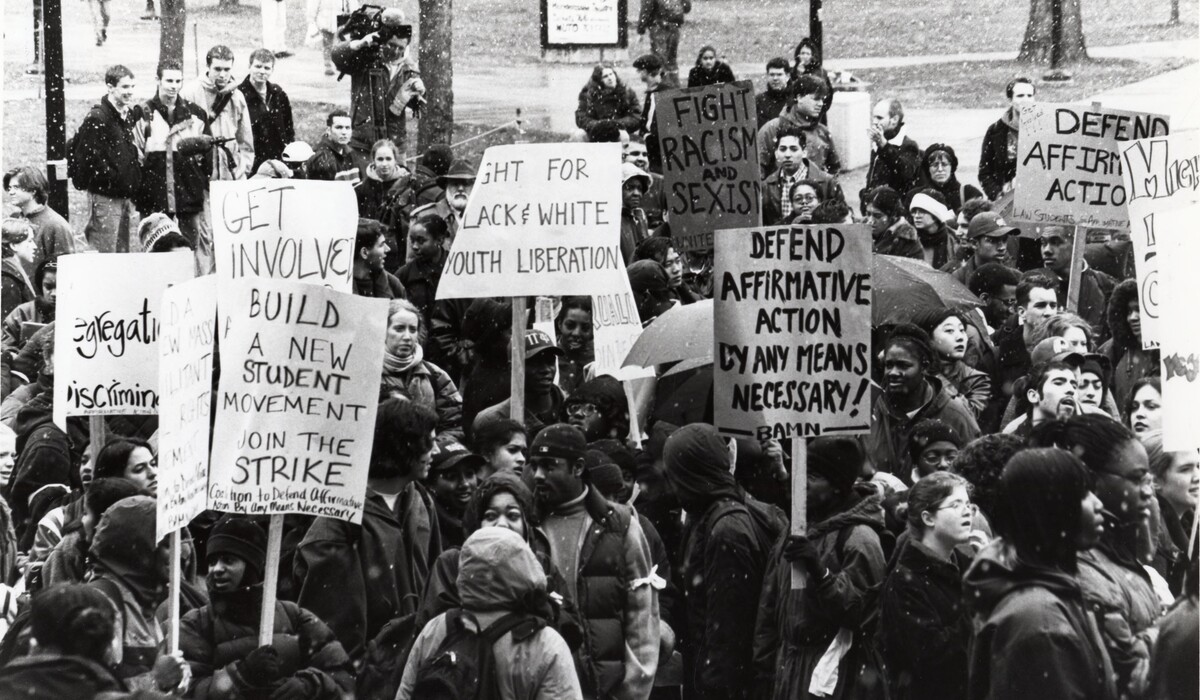

HANNA-ATTISHA: Obviously, the residents are the absolute heroes in this story. For 18 months, they were saying, “Something is wrong with my water.” It never should have gotten to the point that you needed evidence of children having lead poisoning to change the trajectory of the story. So the authorities were denying, dismissing, and ignoring these really organized and vocal outcries from the citizens. I consider myself the last domino in the story. When I presented the data that children were being poisoned from this water crisis, I was attacked. The state said some “wonderful” things about me: That I was causing hysteria, which is awesome because it’s sexist, too. That their numbers (concerning lead levels) weren’t consistent with my numbers.

HOSEA: Things could have turned out differently. You write about when your brother, who is a lawyer, talked to you about the problems that whistleblowers face.

HANNA-ATTISHA: I am absolutely lucky. I was attacked for two or three weeks. That is nothing compared to people, not only in Flint, but in other communities. The lead crisis in D.C. was a cover-up for years, and people who have gone through this are traumatized—with something like whistleblower PTSD.

HOSEA: What was the key to getting the authorities to admit the water was dangerously contaminated?

HANNA-ATTISHA: There were a lot of keys. It was about having a great team. It was being persistent, science-savvy, and vocal.

CLARK: One reason why Flint exploded in the international news the way it did, as opposed to a lot of other communities that have similar challenges, is the very unusual context in which it happened. Emergency management revealed the power structures in a more bold way. So I’m really interested in this as a story of power. Flint’s history as an American town that thrived under General Motors brought a level of drama to the narrative that I think people fed on as this story unfolded. I didn’t find this out until last summer, but my Grandma Rose was actually born in Flint and her father was a GM worker and took part in the 1936 sit-down strike.

HOSEA: You talk about the structures of power. After all the research you both did for your books, are there still questions you would like to ask government officials?

HANNA-ATTISHA: I would have loved to have been in the room when that decision was made to switch to the Flint River water. I mean, you talk to anybody in Flint and they were like, “What?!” I was talking to a videographer who said, “I remember when we could light a match on the Flint River.” The Flint River did not cause the crisis; it was the lack of treatment. But who was in that room, and what were they thinking?

CLARK: That is the mystery question. Some things have come to light. We know that the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality didnít use corrosion controls, but there are a lot more questions to ask.

HOSEA: On a more personal note, is there a particular person or event that really stays with you?

HANNA-ATTISHA: It’s always the kids that inspire me to do this work. And in my book, I talk about special kids—two sisters who I cared for at the beginning of this crisis, before I knew there was a crisis, when I was encouraging them to drink the water.

HOSEA: How are they doing now?

HANNA-ATTISHA: They’re doing well. It takes long-term continuity of care. I often say I suddenly went from holding one tiny hand at a time to holding the hands of an entire city of kids. So we have put into place things that aren’t being done anywhere in the country right now. We have two brand new child care centers. We have near universal preschool and Medicaid expansion. Flint used to have one book for every 300 kids. Now we have home delivery of books every month. Lead is an irreversible neurotoxin, but you can do other things that promote children’s development.

HOSEA: How about for you, Anna? Is there anyone in particular who moved you?

CLARK: I came to Flint for my first extended stay in May 2015. Someone I had interviewed for an article, but had never met in person, invited me to stay with her. When we said hello for the first time, she gave me my own key. Her home ended up becoming my base while I worked here. She became a friend whom I admire deeply. Every day at sunset, at the exact same moment, she and her husband had a ritual they loved sharing of ringing a bell in their yard. That sense of community has stayed with me and informed my writing. I think that is sometimes lost in the chronicle of Flint woes covered in news stories. The community here are repurposing vacant houses to serve different needs, like farming in vacant lots and creating an apprenticeship program for youth called the Wellness House. There’s a reason people love this place.

HOSEA: Talking about how you view Flint, Mona, it seems related to the story of your family, Iraqi immigrants who fled persecution under Saddam Hussein.

HANNA-ATTISHA: I could not write a book about Flint without writing about my family. It is the lens through which I view the world. Here I am in the U.S., and an entire city was just poisoned. It was all part of how I saw government, how I saw power, and how I saw my role in regard to service and justice. This is not just about water or environmental health. Itís about democracy.

CLARK: I appreciate the global context you’re bringing, Mona, because in a time of climate change, the people who have power over fresh water are going to become increasingly powerful. Flint is a battleground for who gets to make decisions about who has water. I would like to think that this has shaken people up to make sure that our public agencies are putting the public good first.

HOSEA: I wanted to know how Flint has changed you both?

HANNA-ATTISHA: Flint is what made me a pediatrician. Now it has given me this microphone to advocate for kids everywhere because there are kids all over the country waking up to this very same nightmare of injustice, lost democracy, environmental contamination, and poverty.

CLARK: It’s still changing me because I have found a community that is going to be part of my life. This is a hard story to tell, but it’s important to attempt to. Because what the hell are we doing if we’re not trying to put more truth in the world?

Leana Hosea, currently a fellow in U-M’s School for Environment and Sustainability, is making a documentary, “Thirst for Justice”, about water contamination and the erosion of democracy. She previously was a Knight-Wallace Fellow at U-M and a BBC journalist.