These Are Their Names

•

Historical Photos courtesy of the U-M Bentley Historical Library

As Dr. Richard E. Smith, ’73, flipped through publications celebrating the University of Michigan’s bicentennial in 2017, he couldn’t help but notice what was amiss from the 200-year history painted by the stories and timelines of his alma mater’s past.

“All I could think was, ‘where are all of the Black people?’”

This was surprising for Smith, who proudly declares the University as the start of his journey. He is part of a three- generation family of Wolverines dating back to 1944 and earned his undergraduate degree in 1973 before attending Howard University College of Medicine. In 2020, he retired as vice president of physician outreach from Henry Ford Hospital after a 45-year career as a nationally recognized obstetrician-gynecologist. Smith was also the first African American president of the American Medical Association’s Michigan State Medical Society.

As an alum, a former U-M clinical assistant professor, nephew to Edgar Smith, ’51, and the father of two Wolverines — Karyn, ’11, and doctoral candidate Richard, ’13, MS’14 — Smith is a first- hand witness to the remarkable things achieved by African Americans at U-M.

“In this 200-year history of Michigan, there was only one brief article about four African American athletes, and I was curious about this,” he recalls. “That was a reminder that even after two centuries of contributing to this institution’s history, there’s still this fixation on African Americans as athletes and not as scholars, so they’re missing all of these other remarkable Black stories that help paint the full picture of U-M’s history.”

Smith thought of all the doctors, lawyers, artists, war heroes, and leaders of racial justice movements; the earliest Black students who, despite institutional barriers, forged paths for themselves at the University and made remarkable contributions to this world. Each individual experience shaped the history of African Americans at U-M and, collectively, paved the way for future generations through the planting of roots.

Unsettled, he sat down and penned a letter of grievances, leading him to Brian Williams, an archivist at the Bentley Historical Library who was spearheading a long-term project on the history of African Americans at the University — a website, appropriately named the African American Student Project.

When Smith contacted the Bentley in 2017, the project housed a growing database documenting every African American student who enrolled at the University between 1853-1956, but Williams and his team were working to expand the database and build an accompanying collection of archival materials and data.

Smith was just the kind of armchair historian this project needed; he had already spent years dedicated to learning and chronicling the history of African Americans at the University. Smith remains an involved member of the U-M Epsilon Chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, the first African American Greek organization at U-M, and serves as a historian, dutifully documenting its founding and growth since 1909. In 2021, he published the book, “The Origins of Epsilon Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc.: Timeline at the University of Michigan.”

Over the next five years, with insight and stories from alumni like Smith and others, the project would evolve to paint a more vibrant, accurate picture of how African American students carved out lives for themselves on campus.

An origin story of origin stories

Launched in 2016, the African American Student Project’s concept was ultimately born from an inability to answer questions about African American student life and history.

“For better or for worse, the University didn’t keep track of race, so we had no official way to trace that back or answer these questions or determine things like historic enrollment numbers,” Williams says.

The project’s first installment documented African American students enrolled at U-M between 1853 and 1956.

Thanks to years of research, archival materials from the Bentley Library, and contributions from living alumni, the project has since expanded to include students enrolled through 1970, as well as maps, photos, stories, autobiographies, and biographies about some of the remarkable African American students, shedding light on the diverse nature of their experiences at the University.

Today, the database contains more than 5,800 verified African American students, their cities or states of origin, and their degree fields and types. Most entries even include local addresses and, when known, membership in fraternities and sororities, and relatives who attended U-M.

A comprehensive compilation of this nature did not previously exist at the University and remains very rare for universities across the country.

“The first pass was crude, really,” Williams says of the project’s early days. “I had help from just a few students. We went through all the Michigan archives and looked for anybody who looked African American and started putting their name down on a spreadsheet, then we’d look at alumni records to try and verify that.”

Williams says the library’s collection of alumni records was “hugely valuable,” helping to confirm racial identities and even uncover some significant family connections.

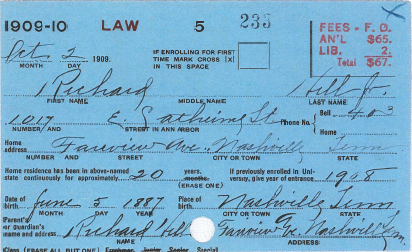

“These records have semester enrollment cards, newspaper clippings, and sometimes photographs that would help us identify students,” he says. “People would indicate if they had family that attended, so we’d keep finding these generational connections that reach long back.”

Project researchers established connections with members of the Divine Nine, the core group of historically Black fraternities and sororities. They consulted census data as well as periodicals and newspapers including The Michigan Daily, the Michigan Manual of Freedmen’s Progress, early volumes of Who’s Who of the Colored Race, and The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP. They also combed through obituaries and searched genealogy sites such as ancestry.com.

As the database grew, it was Smith who offered much of the knowledge and anecdotes that weren’t captured in obits and alumni records.

“When we connected, Dr. Smith did an awful lot of educating for me, particularly about the history of the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity. He brought me all these names and told me why they were important and put together a lot of things that helped to kind of build this timeline for me,” Williams recalls.

Smith had traced groups of some of the earliest African American students coming to U-M from Detroit, Washington, D.C., and Canada as well as prominent universities such as Howard, Fisk, Yale, Williams College, and Phillips Exeter Academy in the early 1900s with what he calls “a unique purpose in mind.”

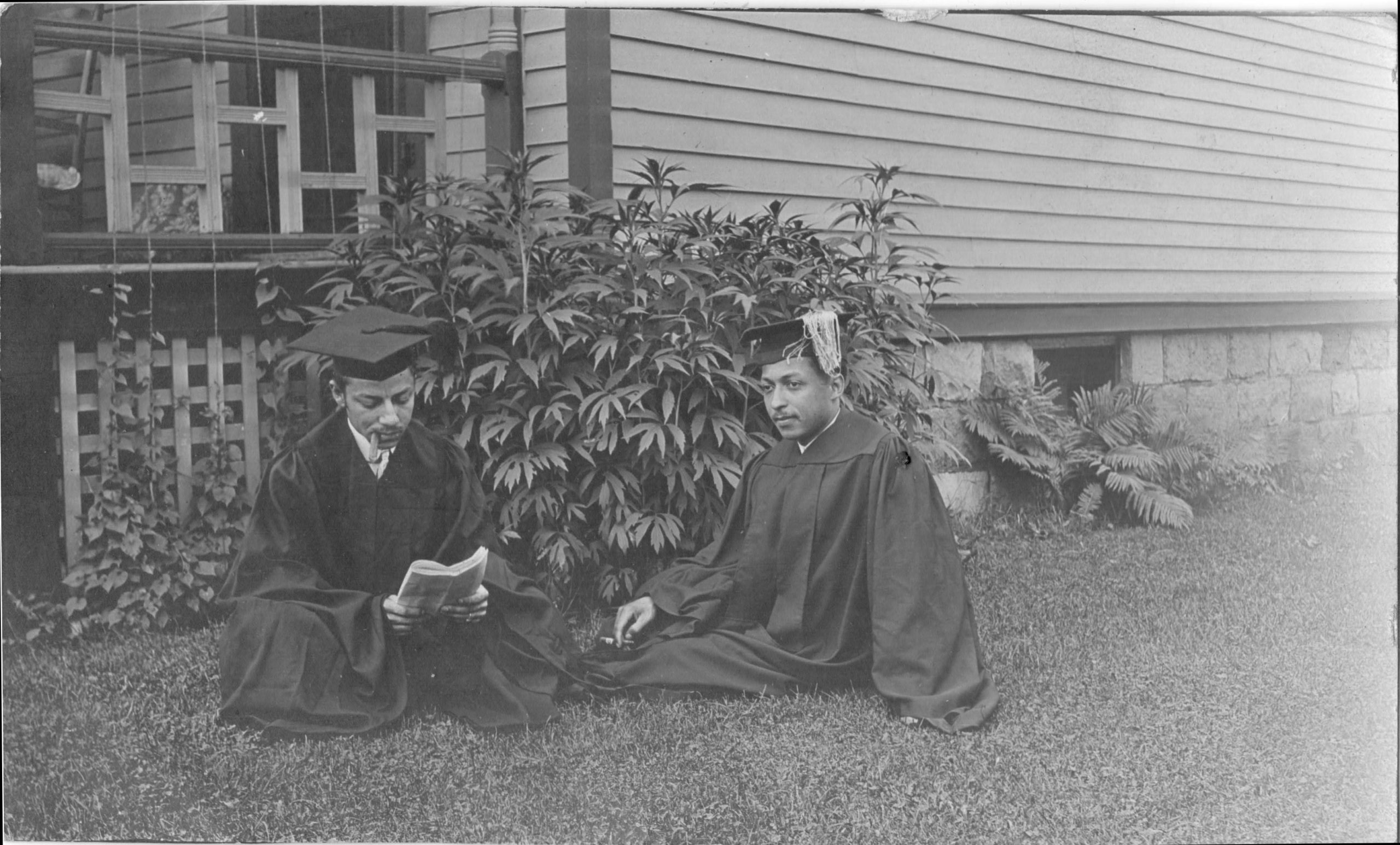

A set of photos for sale on eBay unlocked a rare glimpse into early campus life for Black students

at U-M. For more on the story, click here.

“U-M was a remarkable place to be at that time because it was a smaller, close-knit group of people, and that’s the way it existed in the earliest years. They had this certain bond,” he says. “You have talented people from around the country who came here — musicians, doctors, artists, engineers — and they all came together like a mutual support group, and they helped each other and learned from each other. That’s why so many of them came through medical school and law school with flying colors — because they knew how to teach each other and learn the process of education. That’s why they emerged so strongly.”

Smith also shared the rich legacy of Michigan alums at Howard University’s Freedmen’s Hospital, the first hospital of its kind to aid in the medical treatment of former slaves. It became Washington’s major hospital for the African American community.

Among those alums were John R. Francis, 1878, a prominent medical practitioner during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who became the acting surgeon-in-chief of the Freedmen’s Hospital in 1894; Dr. Simeon Lewis Carson, 1903, who beat out 52 other applicants and became the assistant chief of surgery at 26 years old; and Alexander L. Turner, 1910, MD1912, who, after completing his surgical training at Freedman’s Hospital, returned to Detroit to set up his practice and co-found the Dunbar Hospital in 1918, the first hospital for the city’s African American population.

“These are very talented people who went on to change not only the University of Michigan but the state of Michigan, Detroit, and the world, in many instances,” Smith says. “These students, despite the barriers and unlevel playing field, were a determined group of people who just

did the work. It didn’t matter what they were studying; if they didn’t do well, that meant there would be one less teacher, one less doctor, one less lawyer, and they knew that. So, they had a sense of purpose in coming here to Michigan, and Michigan, of its stature, certainly had a purpose for having them there.”

A grassroots effort

Photo by Doug Coombe

The African American Student Project has identified the “who, when, where” of thousands of Black students, but deeply understanding their experience and sharing their stories are the result of a grassroots effort.

“A lot of people have been very helpful in all of this, like Dr. Smith,” Williams says. “He’s put the word out with all these other groups and helped to open the door to these people who have given us a bunch of names. It’s really spread through word of mouth.”

Williams says students and alumni reaching out helps reinforce why they started this project in the first place.

“I had a person reach out who was an opportunity award program recipient in 1966, and while she was only at U-M for one semester, she wanted to be in the database because it was really meaningful to her; she really appreciated the acknowledgment because it was an important accomplishment.”

Smith says fellow African American alumni are enthusiastic about

being considered and mentioned for their accomplishments.

“There’s always been a feeling that this is our school, this is Michigan, and we bring something to contribute to this, but many feel like nobody is necessarily interested in what they did or they feel ignored,” he reflects. “We say in genealogy that every family has a story, and this is our Michigan family’s story, and this project gives us an opportunity to tell our story.”

That story, Smith says, is one of perseverance, determination, and leadership.

“These are brilliant people who were given the opportunity to come to Michigan because they were super qualified. What they were able to achieve with limited resources — against social barriers with no open doors — was beyond anyone’s imagination. They overcame these barriers because if they didn’t, there wouldn’t be anybody else after them; it was all about creating opportunities for people who would otherwise not have them.”

KATIE FRANKHART is a senior writer for the Alumni Association of the University of Michigan.