The phone call was a shocking plot twist. In early 2014, an editor at Random House called children’s book authors Philip Stead, ’03, and his wife, Erin, to gauge their interest in a top-secret project “involving Mark Twain.” With only those three words to describe the offer, they had to decide if they wanted in.

For the next three years, the Ann Arbor couple were allowed to tell just a few friends and relatives about the extraordinary, mysterious assignment they’d taken on: to finish and illustrate the only known children’s story to spring from the mind of arguably America’s greatest author.

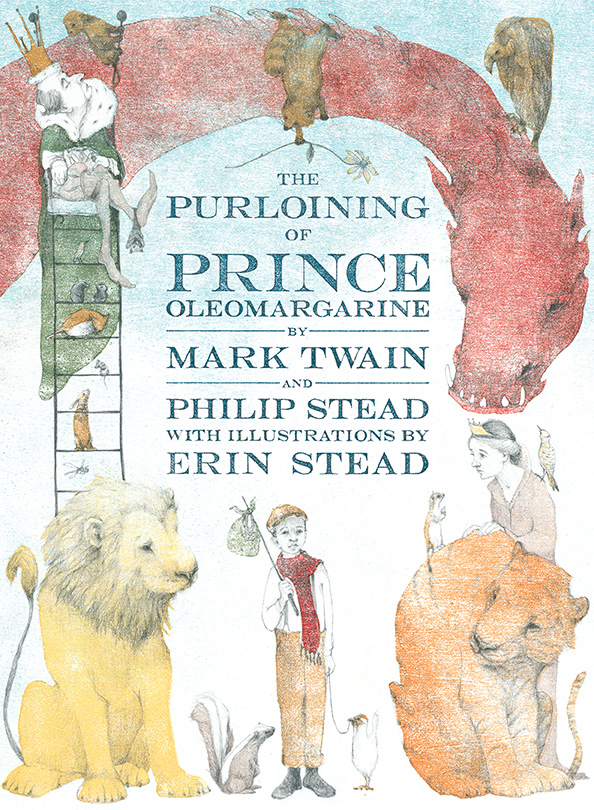

As “The Purloining of Prince Oleomargarine” hits bookstore shelves on Sept. 26, the Steads braced for a level of attention few children’s authors ever attain.

“We’re always nervous, but this is different,” Erin Stead said in June as they awaited the birth of their first child. (A daughter with the kid-lit-ready name Adelaide Jane made her debut a few weeks later.) Both are experienced, successful authors—their first book together, a collaboration called “A Sick Day for Amos McGee” that he wrote and she illustrated, won the prestigious Caldecott Award in 2011 and has been reprinted in 17 countries. But, Erin added, “this is a different level of everything.”

The Steads were confronted with the challenge of turning 16 handwritten pages of Twain’s notes with no ending into a modern picture book that honored both the deceased author and “our own storytelling impulses,” Philip said.

Twain used to make up bedtime stories for his two young daughters by incorporating words or objects they would choose at random from magazine advertisements. But plot points for “Oleomargarine” were the only ones he appears to have written down. “What was great was that we’d look through it and it was already filled with the things that we would naturally want to put in the story,” Philip said.

Philip has authored and illustrated several books. However, for the Twain project, as for “Amos McGee,” he wrote the text and Erin created the artwork. In September 2014, he ensconced himself in a remote cabin on Beaver Island in Lake Michigan to write the manuscript, first reading Twain’s recently released 2,200-page, three-volume autobiography to get into his voice. (Per Twain’s edict, the opuses were published only after the centennial of his 1910 death.)

Collaborating with Twain was understandably tricky. Stead promptly found himself in ongoing dialogue and argument with his co-author’s ghost, especially over the fate of the old woman who gives the protagonist some magic seeds. Twain killed her off in his notes; Stead doesn’t. A kangaroo in the original notes becomes a skunk because Stead decided that would be better for the story.

The result is a beautiful—and, for a children’s picture book, unusually long at 152 pages—tale about an impoverished, lonely boy who acquires the ability to speak to animals and uses that ability to find the missing son of the arrogant, power-mad king. Erin’s artwork is the product of a method involving carving characters into wood blocks, printing ink blots of those blocks, and then using pencil to flesh out the details. To honor Twain, the book contains some homages, making the boy’s home look like the Missouri house where Twain was born and modeling the queen after his wife, Olivia, among others. There’s even a reference to huckleberries, a call-out to Twain’s classic “Huckleberry Finn.”

Still, both Steads know some of Twain’s most ardent fans may rebel against their approach.

“The thing we told ourselves going in was, if we were going to collaborate with this guy, we couldn’t admire him; he had to be a collaborator,” said Philip, who takes an unconventional, meta turn by making Twain and himself characters in the book who argue about the direction of the plot. “We had his notes but we weren’t enslaved to them. Every now and then we’d get to something in the notes and I’d say to him, ‘We can’t do it this way. Even though you’re Mark Twain, you’re not an expert in children’s literature, and we are experts in children’s literature. For that reason, this character should be a skunk.’”

In addition, the Steads had guidance from Twain’s now-deceased daughter, Susie, who wrote in her biography of her father that she wanted the famously acerbic author to write something “that would reveal something of his kind, sympathetic nature.” That, the authors said, granted them license to rein in some of Twain’s darker storytelling instincts for “Oleomargarine.”

“This is what we thought we could bring to the tale that Twain himself would have a hard time doing because if he had a choice between being genuine or being funny, he’d pick being funny every time,” Philip said. “If we had a choice between being funny and being genuine, we pick genuine. The two things together, we think, make it work.”

The Steads are fortified against any ire by having some powerful allies in the Twain-verse. The literary agent who handled the Twain autobiographies is on board, as are leaders at the Twain archives at the University of California at Berkeley and the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut, which will receive royaties.

In fact, the project started when a scholar, John Bird, went digging through Berkeley’s vast Twain archive for, of all things, material for a Twain-inspired cookbook. (Surprisingly, several already exist, a reflection of the author’s enduring brand value.) Bird came across the word “oleomargarine” in a document heading and thought it was culinary-related but soon concluded that Twain’s daughters must have chosen an advertisement for the butter substitute to prompt a bedtime story back in the 19th century. Bird brought the notes to the attention of the Twain House, which contacted Random House’s Doubleday Books for Young Readers, who hired the Steads. The publisher has a major rollout planned with an initial print run of at least 175,000—monstrous for a children’s picture book.

The closest thing to criticism so far has come from Robert Hirst, curator of the Twain archive. “If you’d ask me to finish this text, I would not have come up with this,” he said. “But that’s OK. If they think this is going to sell and make some money for the Twain Hartford House, I’m all for it. Accuracy is very important to me, and fidelity is very important. But I try not to let that obsession interfere with other people’s point of view.”

The Steads’ rise to the heights of the kid-lit world began at U-M. They met in 1999 in a high school art class in Dearborn, Michigan. Philip, a state 800-meter running champion, chose U-M for college because he sought a school with both a well-regarded art program and a top-notch track and field squad. He’d become enchanted with the idea of creating children’s picture books in high school after seeing a pamphlet showing how the legendary author Maurice Sendak created his classic “Where the Wild Things Are.”

U-M didn’t—still doesn’t—have a program for illustrators, but he fell under the apprenticeship of Professor William Burgard, known locally for drawing the eye-catching posters for the Ann Arbor Summer Festival. The two devised a special curriculum of independent study to give Philip the kind of art instruction that would form him.

Then, in his sophomore year, he and Erin, who is two years younger and then still in high school, began frequenting Kaleidoscope Books in Ann Arbor. Owner Jeffrey Pickell’s eclectic collection was made up of rare and collectible books, including children’s literature. In addition to the couple’s own searching, Pickell would point out forgotten authors of bygone years and sell them at progressively deeper discounts to the enthusiastic young couple. Philip would take them back to Burgard to study the work.

“We’d talk about how I might go about mimicking someone’s art style,” Stead recalled. “You’re kind of an archeologist at that point because you have the printed image but not the actual art in front of you. You’re trying to figure out how someone made it, and as you try to figure out what that process was, you end up figuring out new processes.”

Another uniquely Ann Arbor element of Stead’s personal art history was a gig as an illustrator for Zingerman’s, drawing the images for the legendary deli’s mail-order catalog as a senior and after graduation from U-M. “The biggest benefit was a free meal every day,” he said. “I was probably the only college kid in town that was eating five Zingerman’s sandwiches a week.” Erin went on to art school in Baltimore and New York; they married in 2005 and have lived in various parts of Michigan since 2008.

Pickell was among the few the Steads told about the Twain project early on. The couple had remained close to him, with Erin employed at the store while the couple worked on “Amos McGee” in 2009. In fact, Pickell, upon seeing the final illustrations, prophetically deemed it a Caldecott-worthy book. The owner, who closed the brick-and-mortar shop in early 2017, gushes about their success.

“It’s like a fairy tale,” Pickell said. “It’s like somebody doing exactly what they want in the exact way they want and having a partner who is also doing those things and loving it together and struggling in order to get to a place that they are today, which is the height of the children’s book world.”

In addition to “Oleomargarine,” the Steads each have other books out this year and three more between them due out in 2018. But they know this collaboration could be their best-known effort. “This was a different opportunity specifically because it left room for us to collaborate,” Erin said. “I think Twain would be irritated with us. We try our best to make him happy, but we’re never going to be him.”

Whether that’s OK with readers—especially Twain purists—remains to be seen.

“It kind of goes to the question of whether art is something that continues to have life after it’s made or if it’s something that becomes a relic immediately after it’s finished,” Philip said. “Most artists would prefer to think that their work is something that can go on living and changing and being experienced in different ways. Sometimes it’s the fans, not the creators, who think of it as something that can’t be changed.”

Steve Friess is a freelance journalist based in Ann Arbor.