The line snaked out the door of the new, modern building next to the Kelsey Museum and made its way down State Street. But the hundreds of visitors eager to get a first glimpse of the William Monroe Trotter Multicultural Center at its April 11 opening didn’t seem to mind a bit of a wait.

After all, the moment was nearly 50 years in the making.

From the protests of the Black Action Movement (BAM) in 1970 to the 2013 social media campaign known as Being Black at the University of Michigan (#BBUM), the goal of a cultural center has motivated generations of U-M students.

“This is what we worked for our senior year,” said Grace Sims, ’14, who was part of #BBUM, and now serves as director of Mary Markley Hall. “It’s definitely what we always deserved as students.”

In 1970, U-M’s black students shared that sentiment, envisioning a place where they could set down the burden of being a minority at a majority-white university. The idea had emerged out of BAM’s effort to demand more resources for African Americans on campus, including greater recruitment efforts.

“We were the generation that had grown up at the end of the modern civil rights era,” says Cynthia Stephens, ’71, who was vice president of the Black Student Union while at U-M. The organization was involved in the formation of the three BAM protests in 1970, 1975, and 1987 as well as organizing #BBUM decades later. The 1970 movement’s most well-known demand was that the proportion of black students—who then made up less than 5 percent of the student body—be increased to 10 percent. Another aim of the months of protests and student strikes was, as Stephens puts it, “to have a place to gather.”

It wasn’t that black students were shut out of other spaces—they could use the Michigan Union and the Michigan League. “But there was a feeling that you were questioned if you went,” says Stephens, today a judge on the Michigan 1st District Court of Appeals and an active alumna. “If the default system is white, then everything else is other.”

The regents agreed to provide a space for the students in a former annex to the School of Education. The Martin Luther King Jr. Scholarship Fund, which depended on donations from the campus community, supported the center, but the University moved a few satellite counseling offices there. The hope, in the words of Charles Kidd, MSE’64, MS’67, PhD’70, then vice president for student services, was “to broaden the base of contact” with an underserved population.

For the most part, figuring out how to use the building was left up to the students themselves. And it took work to make the three-story, 50-year-old house at the corner of South University and East University avenues a true home for U-M’s black community. For weeks before it officially opened in November 1971, a dedicated group of students made repairs, painted, decorated, and furnished the ramshackle old place that would serve, in the words of a 1975 Michigan Alumnus article, “as the home-away-from-home for U-M’s black students.” Alex Hawkins, MSW’75, served as Trotter’s first director.

Among the initial orders of business was to come up with an official name. Stephens says Thaddeus “T.R.” Harrison, ’72, JD’78, came up with the idea of naming it after William Monroe Trotter. A black Boston newspaper publisher and advocate for racial justice, Trotter was known as an uncompromising opponent of segregation. Although Trotter had no connection to Michigan, Harrison, who died in 2010, apparently admired his vehemence.

The first Trotter House was in use for a mere six months before a fire, caused by a faulty hot water heater, rendered it unusable. To replace it, U-M purchased the former Zeta Psi fraternity house on Washtenaw Avenue, a bigger space at 12,000 square feet. Harrison, then a first-year law student, was appointed the new building’s director.

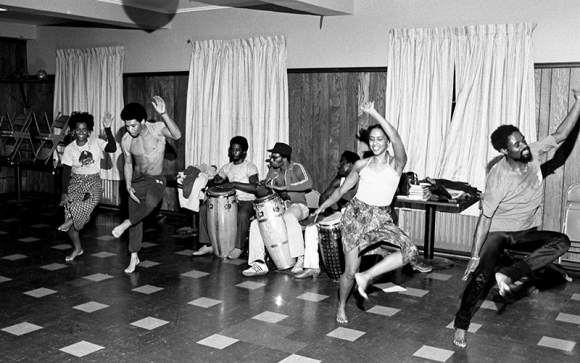

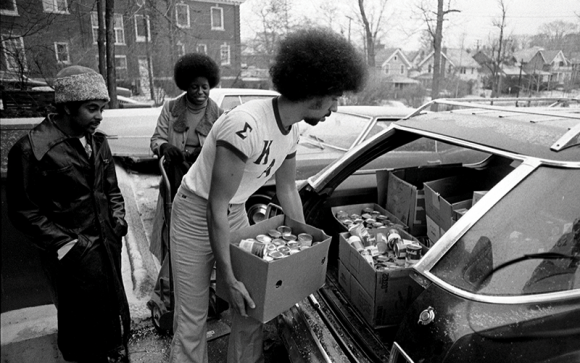

By the mid-1970s, Trotter was hosting regular community events, art shows, and celebrations of black culture. The Trotter House Dancers choreographed their own numbers to traditional African music, jazz, and Nina Simone songs. A handful of students worked as staff members and lived on the premises. Others took advantage of study, meeting, and party space, or organized workshops on topics as diverse as meditation, karate, and hair braiding. A dignitary from Upper Volta (today known as Burkina Faso) paid a visit to Trotter to receive donations U-M students had collected for drought victims.

“Here, together, we can maintain our cultural identity and not feel that we are being swamped,” said then-house manager Lois Owens, MSW’71, in an Ann Arbor News article.

All along, however, members of the campus community who used Trotter House—which became the Trotter Multicultural Center in 1981 to acknowledge its changing role—complained about the location. A long walk from campus and surrounded by fraternity houses, it was both a practical problem and a symbolic one.

“If the message is that the University is inclusive of difference, then it should be inclusive of difference at its heart and not its periphery,” says Stephens.

It would take another generation, and another movement, to make the new, centrally located, and purpose-built Trotter a reality. In 2013, #BBUM organized to generate conversation about life for African American students on campus. In some ways, little had changed since 1970—one of the Black Student Union’s seven demands was increasing enrollment to 10 percent, the same goal of the original BAM. In fact, by 2013, the percentage of black students was 4.6 percent, down from a high in 1999 of 8.4 percent. And the Trotter center, in poor condition and underfunded, was not meeting the needs of the many campus communities it was meant to serve.

This time, however, it didn’t take shutting down U-M (as happened in 1970) to get leadership to notice. In February 2014, the University committed to building a new center.

“Make no mistake, we would not be here if it were not for the students who fought for this very moment,” said Tyrell Collier, ’14, speaker of the Black Student Union during #BBUM, in official remarks at the new center’s ribbon-cutting event in April.

It’s a legacy acknowledged in mural-size historical photographs of campus movements on the walls of the center’s Sankofa Lounge, named for a Ghanaian word that refers to looking back while moving forward. And it’s a legacy that current students appreciate.

“The old building had a lot of character, but it wasn’t really accessible—a lot of people didn’t even think of it as ‘on campus,’” said current student Camryn Banks as she and a group of sorority sisters took in the new Trotter. “I’m really proud and happy to have this space—I’m glad I’m not graduating yet, so I’ll have a chance to use it!”

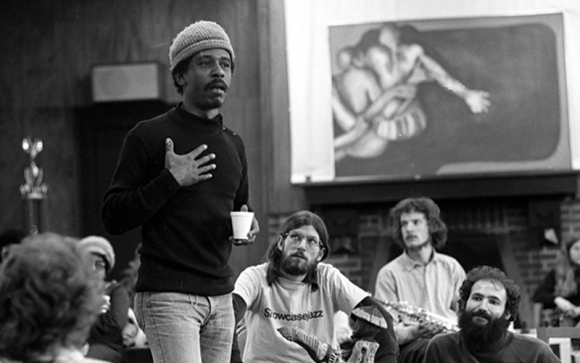

By the mid-1970s, Trotter House was the gathering place for events such as (top to bottom) a jazz workshop in 1977, African dance in 1981, and a food drive for the Salvation Army in 1976.

Amy Crawford is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Smithsonian, The Boston Globe, and Nature Conservancy magazine. Follow her on @amymcrawf.

Historic photos courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library.