Now a U-M legend, Bo Schembechler was little known when he first arrived in Ann Arbor. That changed with his first game, played against Vanderbilt 50 years ago.

IF you had never set foot inside Michigan Stadium and were taking your first, wide-angle look around the place on Sept. 20, 1969—several years before anyone thought to call it “The Big House”—you were likely dazed, actually made dizzy by the abrupt and tremendous expanse of space.

Then your eye might have fixed on the synthetic playing surface below. That summer, the natural sod on the stadium floor had been ripped out and replaced with giant spools of nylon matting. Tartan Turf was the commercial name; Canham’s Carpet was the popular designation. At the behest of then-athletic director Don Canham, Michigan Stadium had become one of the first college football coliseums in the country to install artificial grass—the kind of surface that in time would lose favor for wreaking havoc on hips, knees, and spines.

But at high noon on that sunny September Saturday, the sheet of unexampled green constituting Michigan’s playing field had at least one redeeming quality: the team’s Maize and Blue colors absolutely erupted against the new backdrop. The untested squad, led by its unfamiliar first-year coach, was resplendent.

The field, which one writer said resembled “a massive crap table,” got nearly as much attention as the new coach, a certain Glenn “Bo” Schembechler.

The new guy was a former Woody Hayes assistant at Ohio State and had been head coach at Miami University for six years. On Dec. 27, 1968, Canham announced that Schembechler would succeed Chalmers “Bump” Elliott, a true-blue Michigan man who had been the Wolverines’ coach for 10 seasons and a member of the fabled, undefeated team of 1947. For his debut against Vanderbilt, “Bo Who”—the Ohioan—was greeted with folded arms. Attendance barely reached 70,000.

Indeed, it was another era and a different campus, a hothouse of student dissent, and if football was not exactly a sideshow, neither was it the overriding concern.

Click here to view a video about Bo Schembechler’s arrival on campus.

“At halftime in those days, you could just walk in and see the game without buying a ticket,” says Michigan football broadcaster Jim Brandstatter, ’72, a sophomore lineman on the 1969 team.

Still, there was curiosity about Schembechler. Word spread across campus that the new guy was a bit of a taskmaster, if not a tyrant. The squad he inherited from even-tempered Elliott was put through a diabolical winter conditioning regimen.

“Bump was an intense guy, but Bo took it to a whole new level,” says Brandstatter. “I give the seniors and juniors unbelievable credit because they’d been in the program for years and suddenly the rug gets pulled out from under them. They’ve got this new maniac coming in and asking them to do things they never thought they’d be asked to do.”

Guard Dick Caldarazzo, ’70, a senior in 1969, remembers everything from wrestling drills to players carrying other players up the steps of Yost Field House. Glenn Doughty, ’72, a sophomore tailback, compares Schembechler’s drills to basic training in the military. “All that was missing was the bullets,” he says. “It was pure hell, man.”

By the time spring practice started, players were quitting in alarming numbers.

“A lot of guys said, ‘You know what, I’ve got better things to do than beat my brains out and get yelled out by this crazed man,’” says Brandstatter. “That’s when Bo put up the famous sign in the locker room that read: ‘Those who stay will be champions.’”

The sign hung in the old football training complex on the second floor of Yost throughout spring practice and the fall football season—and has remained in the locker room ever since.

Schembechler was making an impression with the media, too. The day before the Vanderbilt game, Detroit Free Press columnist Joe Falls wrote that if Schembechler had “devoted as much time in the past nine months to studying the stock market or the racing form, or even to digging ditches out on I-94, he’d be a rich man today. Instead he is a man who is apprehensive about the biggest moment in his career.”

Apprehensive, but not nervous.

“Remember, I’ve spent the last 15 years getting ready for this moment,” Schembechler told the writers. “I may blow some plays but it won’t be because I am tight.”

The visiting Vanderbilt team did seem anxious.

“When we walked into the stadium that seats 100,000—oh my God!” says Pat Toomay, one of the Commodores’ defensive linemen. “I watched the films not long ago, and we looked like a bunch of insects in the path of a bus.”

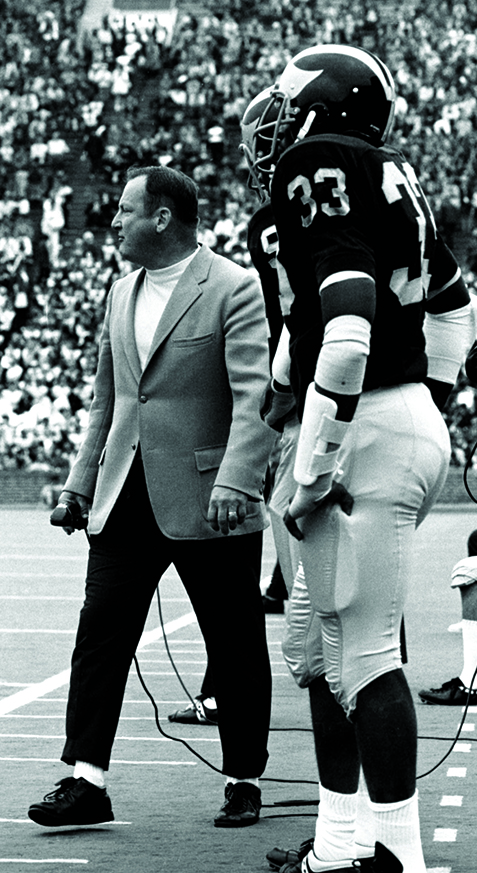

On the Michigan sideline, the new era was palpable.

Elliott had been a tranquil figure during a ballgame. His successor was a dynamo. In his column the next day, Falls wrote: “Schembechler paced the sidelines like the expectant father he is. … He jumped up and down with his players in the team huddle before the game … called every offensive play … lectured his offense almost every time it came off the field, even after it scored. And he knelt there on the smooth tartan turf and drew diagrams in the carpeting for the young quarterback, Don Moorhead.”

From Foes to Friends

VANDERBILT’S Pat Toomay was exhausted at the conclusion of Michigan’s 42-14 win over his team on Sept. 20, 1969, but the Commodores’ imposing, 6-foot-5-inch defensive end was also greatly impressed. As jubilant Wolverines made their way off the field, Toomay began searching for Garvie Craw, ’72, Michigan’s gritty fullback, who had scored his team’s first touchdown and blocked brilliantly all afternoon. He finally spotted No. 48 on his way to the tunnel and jogged over to him.

“He came up to Garvie and said, ‘You guys are really good; you kicked our ass,’” remembers Dick Caldarazzo, ’70, who started on the Wolverines’ offensive line. “He followed the progress of our team for the rest of the season, and after we beat Ohio State he sent a telegram to Garvie that read, ‘You guys are awesome … Toomay.’ Garvie kept that telegram.”

Toomay, who would play 10 years in the National Football League, thus became part of the lore of Michigan’s 1969 championship team.

Craw, a 6-foot-2-inch 218-pounder, scored 13 mostly short-yardage touchdowns that season for the Wolverines, but Caldarazzo called him “one of the greatest blocking fullbacks ever to play in the Big Ten.” On Sept. 20, Toomay had taken the brunt of some of those blocks.

“He was a real load, a human bowling ball,” Toomay says. Except for the telegram that November, there would be no communication between Toomay and Craw for 37 years—until March 2006, when Craw discovered the message while cleaning out his attic.

“He got in touch, and we started chatting,” says Toomay. “He was delightful, extremely intelligent, with a wonderful sense of humor.” Among other things, the two men discussed their shared Scottish ancestry, which they each traced to the country’s southern uplands. “It was quite powerful to figure that out—especially with that contact out of the blue after all those years,” says Toomay. “He also spoke about his son, who was a soldier in Afghanistan and was trying at that time to adjust to civilian life again.”

Soon after, Craw was diagnosed with cancer of the esophagus. At that point, the conversations became more serious, says Toomay. “But he maintained his wit to the end.” Craw died on July 27, 2007, at age 59.

In 2011, Toomay returned to Ann Arbor for the first time since the 1969 game, touring the campus on the invitation of his elementary school basketball teammate, Anthony Elliott, the University’s acclaimed music school professor and cello soloist.

As Elliott drove his old friend past Michigan Stadium that day, memories of the 1969 game flooded back—led by thoughts of Garvie Craw.

The coach’s apparel was different from the iconic Schembechler ensemble of later years: blue windbreaker, Block M baseball cap, bulky headset. On Sept. 20, 1969, he wore a tan sport coat over a white shirt and football shoes with white socks; instead of a headset, he talked to the coaches upstairs on a radio telephone. And he was hatless.

The seniors and juniors knew Elliott’s sideline style, but the players had never seen Schembechler coach a game, says Brandstatter. And it was different.

“He was into it. He was coaching, man. He called all the offensive plays and sent them in to the quarterback. He was on the phone to (assistant coach) Jerry Hanlon in the press box, grabbing a player and sending him into the game with a play and chattering and saying, ‘We gotta do this against that guy and they’re running that wide tackle’—that’s the way he coached.”

Moorhead, ’78, the junior quarterback whom Schembechler called “Moose,” was starting his first varsity game. After breakfast that morning, he met with the coach. “Well, Moose, what play do you think we should start with?” Schembechler asked. Moorhead suggested an iso option play, and the coach agreed. “So my very first play of my starting career, we run option,” Moorhead says. “And I think we ran for like 10 or 12 yards, and that helped to get rid of a few jitters.” But the play that decreed a new era of Michigan football—one that extends to the present day—came a bit later, after Vanderbilt had punted into the end zone and set up Michigan at its own 20. On his first carry, Doughty (who had been a wide receiver but started his first varsity game in a new position as tailback) dove off-tackle. He was hit at the line of scrimmage, bounced to his right, found a hole, slipped a tackler, and sprinted to the corner of the north end zone.

He couldn’t understand why he hadn’t been given the ball before that touchdown run.

“Finally, on the first play of the second quarter, Bo let me go and I ran for 80 yards,” he says of that moment. After he scored and came back to the sidelines, Schembechler told him he had run through the wrong hole.

“I was so happy, I didn’t care what he said.”

Michigan won handily, 42-14, commencing a regular season that would end nine weeks later with a historic upset win over an Ohio State squad dubbed by the media the “greatest college football team of all time” and a co-Big Ten champion. A new age of Michigan football had begun.

Elliott’s new job was associate athletic director, but he was in the WWJ radio booth during the game, providing color commentary for the broadcast while sitting in for Bennie Oosterbaan, another former Michigan coach, who was sick that day.

By the time spring practice started, players were quitting in alarming numbers. “That’s when Bo put up the famous sign in the locker room that read: ‘Those who stay will be champions.’”

“To tell you the truth, I was so busy I didn’t really think about it,” he told reporters. “But I miss it, sure. I can’t help but miss it a little.”

But this was Schembechler’s time.

“Everybody was learning,” says Brandstatter. “The input you were getting into your soft, mushy brain was coming from very different directions. There was Woodstock and we had a guy go to the moon, but we were football players and we had to concentrate. Bo made us concentrate on winning football games. We navigated that. I feel very lucky to be part of that generation.”

Future NFL star Reggie McKenzie, ’72, attributes his success at the next level of football—and in life—to a Schembechler mantra: do it right the first time, all the time.

“I loved him,” McKenzie says. “He was a great coach, and a lot of us owe him for what he created in us.”

In the locker room after the game, Schembechler stood talking to reporters.

“It was pretty good for an opening game,” he said, suppressing the slight trace of a grin. “Everything considered, it was a pretty good performance.”

The new regime was off to a good start.

Beating Ohio State

WHEN Bo Schembechler led his first Maize and Blue contingent out of the tunnel on Sept. 20, 1969, more than 30,000 seats were empty in the “hole that Yost dug” (to partially quote broadcaster Bob Ufer, ’43). A week later, fewer than 50,000 showed up to see Michigan defeat the University of Washington, in what was then a 101,100-capacity Michigan Stadium.

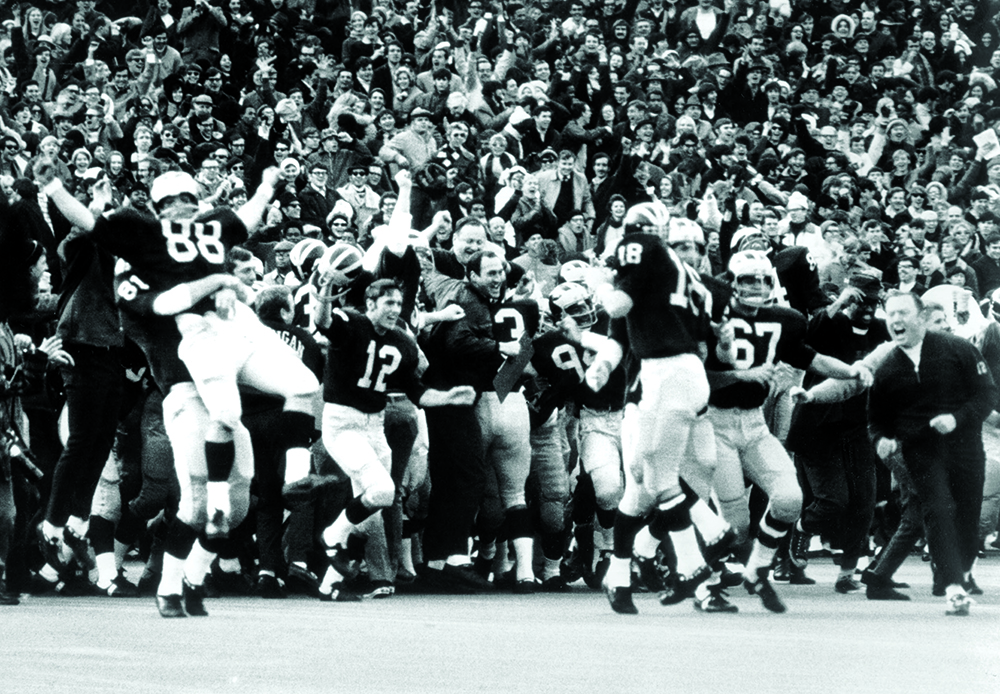

Indeed, the victory that transformed U-M football and began the tradition of the packed Big House (consecutive home games with crowds in excess of 100,000) would not occur for another eight weeks. That victory was the 1969 regular season finale against No. 1-ranked, defending national champion Ohio State.

“We never filled that stadium regularly until we beat Ohio State that year,” said Dick Caldarazzo, ’70, a senior guard on Bo’s first team.

The previous November, OSU had punished an excellent Michigan team led by All-American Ron Johnson, ’69, winning 50-14 in Columbus. Heading into Ann Arbor for the Nov. 22 rematch, the Buckeyes had won 22 straight games, thundering through the 1969 season. The joke was that the only team that stood a chance against Ohio State was the Minnesota Vikings, the NFL powerhouse of the moment.

Michigan had compiled a 7-2 record and racked up four straight blow-out victories yet were 17-point underdogs. Despite the long odds, Wolverine players—many of whom will return to the Big House this Thanksgiving weekend as honorary captains for the 2019 Michigan-Ohio State game—were optimistic going into the 1969 game.

Michigan football broadcaster Jim Brandstatter, ’72, a sophomore on the 1969 team, remembers, “The students, my friends, guys I went to class with, were saying, ‘God, are you guys going to keep it close?’ I’d say, ‘No, we’re going to beat them.’ And they’d look at me like I was crazy. But we had killed every team we played leading up to Ohio State. … We were on a roll and were going to repay them for what they did the previous year to Ron Johnson and that Michigan team in Columbus.”

After a win against Iowa the week before the OSU game, the Michigan locker room was in a frenzy, says Glenn Doughty, ’72, a sophomore tailback. “We were throwing chairs, beating up lockers. We were ready for Ohio State.”

Adds Caldarazzo: “We could have gone out that same day and played Ohio State.” That emotion carried through to the following Saturday in Ann Arbor. “We started pounding the ball down their throats on the first drive,” says Caldarazzo. “They were sweating bullets. I’ll never forget it, Jim Stillwagon (Ohio State’s All-American middle guard) was flush. Hardly anyone ever made a first down against them all season. Bo just had us so pumped up it was crazy.”

Quarterback Don Moorhead, ’78, was less nervous against Ohio State than he’d been in the opener against Vanderbilt on Sept. 20. “I honestly felt that we were better than they were, that we had better personnel,” he says. “In the meeting on Sunday before the game, Bo said he thought we should be the favorites.”

Michigan won 24-12, upsetting the team dubbed by the media as the “greatest college football team of all time.” Barry Pierson, ’71, a defensive back from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, intercepted three passes and returned a punt 61 yards to set up a Wolverine touchdown.

Attendance was 103,588—the first 100,000-plus game of the Schembechler era.

Richard Johnson retired this year as editor of the weekly newspaper Automotive News. The father of three U-M graduates, he attended Bo Schembechler’s first game when he was a high school student.