From teaching students about city neighborhoods to training community service workers to help residents, the University has been an important partner to Detroit. This relationship has grown even closer in the past decade, since former U-M President Mary Sue Coleman inaugurated the University of Michigan Detroit Center in 2005. Michigan Alumnus takes a look at four partnerships that illustrate the strength of these ties.

Sam Morykwas, ’13, grew up in the Detroit suburb of Troy, but he had an up-close view of the city throughout his childhood. His mother worked in a downtown bank, and his father served as information technology support at various charter schools throughout the city.

“My dad was really drawn to the people there,” Morykwas says. “He got to know them, appreciate their culture, and show a lot of love to the people he worked with.”

In his freshman year at U-M, Morykwas began to do volunteer work in an urban garden in Brightmoor, a neighborhood in northwest Detroit. “There was a lot of good work being done in the city,” he says, “and a lot to learn there.”

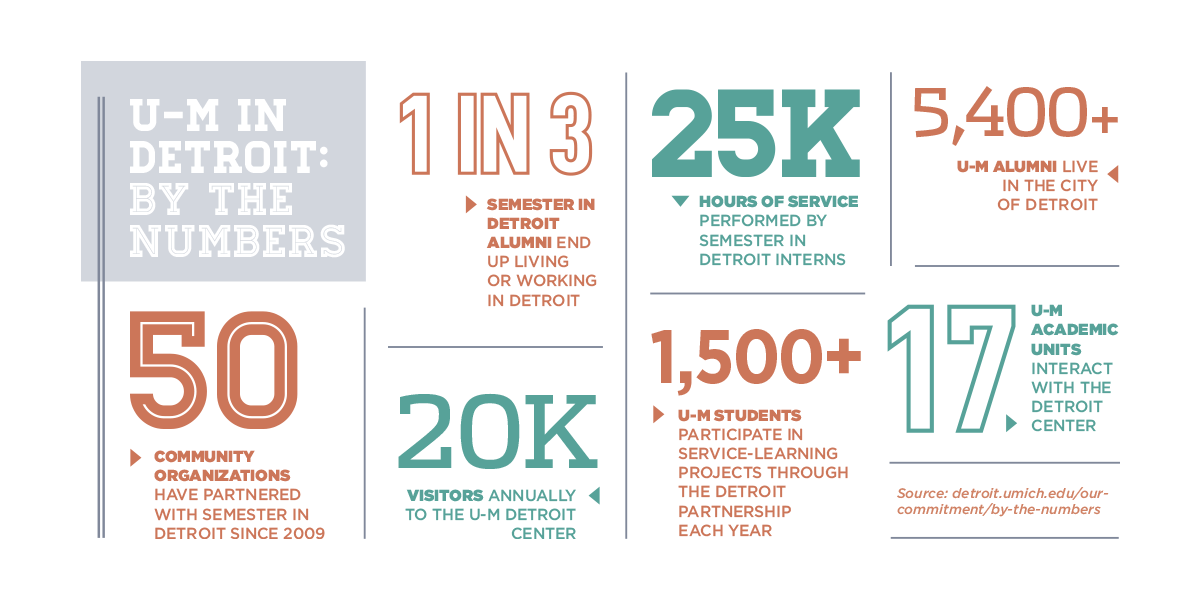

During his sophomore year, he was thrilled to hear about Semester in Detroit. The program started in winter 2009, with 14 students working on a variety of projects in conjunction with local organizations. The aim was to combine education, community engagement, and social justice. Since its conception, Semester in Detroit has hosted more than 175 students, working with more than 50 nonprofit organizations in the city.

“As opposed to study abroad,” Morkywas says, “it’s study domestic.” Because he already knew the area, he requested placement in Brightmoor, allowing him to get to work and forgo the usual transition that U-M students experience when they begin their projects in the city.

Morykwas went back to work in the urban gardens, this time with a community group called Neighbors Building Brightmoor. The projects he helped facilitate included an after-school program for elementary and middle school students, art and music classes, and a summer festival for kids to show off their skills. He also set up the organization’s website and social media presence.

After graduating with a degree in political science, Morykwas spent a service year working in Lansing, Michigan, with AmeriCorps. But Detroit called him back. He moved to the city, landing first at the Detroit Science Center. More recently, he serves as the marketing manager for the Eastern Market Corp., which oversees the city’s sprawling farmers market just east of downtown. (See page 37.)

He says he learned a series of lessons from his Semester in Detroit experience.

“The key thing is just giving people exposure to different parts of the city that they may have never seen,” Morykwas says. “They should have a different understanding than just what they see in the headlines.” He adds that some participants have a misperception of how they can most help the city.

“They go in thinking, ‘Let me give you food! This is what you need!’ Maybe the community doesn’t need food; it needs health care, or maybe it needs the street cleaned.” Semester in Detroit, he says, “teaches you to understand the issues from the people living there.”

Joel Batterman, MUP’12, doesn’t own a car, and yet he frequently travels in, and between, Ann Arbor and Detroit. He relies on public transportation, his bicycle, car pools, and especially the Detroit Connector, a bus from campus to the city.

Batterman emphasizes that he didn’t create the Ann Arbor-Detroit shuttle, which began in 2013 with funding from a provost’s office grant. But he has helped it to thrive and has become the U-M figure most associated with it. A tireless advocate for public transportation, Batterman, currently a Ph.D. candidate in urban and regional planning, led a petition drive in 2015 to ask U-M President Mark Schlissel to reinstate the service when its future appeared in doubt.

Now, the Detroit Connector runs seven days a week, originating in Ann Arbor and making stops at the UM-Dearborn campus and the U-M Detroit Center in the city. This year, for the first time, the public has been able to ride the bus, too.

“There are a lot of students who don’t have cars. Ann Arbor is a place where it’s pretty easy living without a car. But they would not be able to get to Detroit without a private car,” Batterman says. He adds, with a laugh, “I see a lot of students taking it home on Fridays, some of them with laundry.”

Batterman, who grew up in Ann Arbor, got a better sense of the importance of public transportation when he left home to attend Reed College in Portland, Oregon. His undergraduate research focused on Detroit and its racial divide. At the same time, he experienced the well-developed public transit system in Portland.

He wondered if, by going out to Oregon, “I was taking white flight to the next level and kind of running away from the struggles of Detroit and other industrial cities,” Batterman says. “I did feel like perhaps I had an obligation to come home to Michigan and try to be useful in some way.”

Batterman returned to Michigan to earn a master’s in urban planning at U-M and got involved in Detroit’s campaign for better transportation. He is coordinator of the Motor City Freedom Riders, a Detroit advocacy group made up of bus riders and their allies. The organization’s name is a nod to the civil rights movement, which reflects how Batterman feels about transportation.

“We really believe the right to move about is a fundamental human freedom,” Batterman says. “The lack of public transit is an issue of racial and economic justice. We really need transit so the hundreds of thousands of people in the city without cars can have access to jobs and education.”

The University has a key role to play, Batterman adds. “We need to build a bigger movement, not just for transit, but for racial and economic justice in the region, because for so long, we’ve just denied all kinds of resources to our central city of Detroit.”

THE DETROIT CENTER

Since its opening in September 2005, the U-M Detroit Center has symbolized the connection between the University and the city. Not far from U-M’s original 1817 location, the center is a resource that boasts spaces for the collaborative work of several schools, colleges, and units that partner on programs within the city. These include the College of Engineering’s Michigan Engineering Zone and the School of Social Work’s Technical Assistance Center.

It also provides a location for the U-M Detroiter Hall of Fame, which honors distinguished alumni who originally hailed from Detroit (think poet Marge Piercy, ’57, and actor David Alan Grier, ’78), and the Monts Hall Gallery, which features exhibits by University, local, and K-12 student artists.

“Providing a home for our many Detroit projects in the heart of the city’s cultural center makes us far more visible and accessible and enables us to be a part of its revitalization,” said then-UM President Mary Sue Coleman upon the opening of the center. “We look forward to the way this center will strengthen the partnership between U-M and Detroiters.”

In the 1930s, the Chicago School of Sociology became the first major organization to research social programs in the nation’s cities. In the mid-1980s, another academic movement, the Los Angeles School of Urbanism, emerged to focus on contemporary urban problems.

Now, a number of faculty members are advocating for U-M to create the Detroit School of Urban Studies, arguing

that the University can become an academic leader on issues facing Detroit.

Margaret Dewar, emeritus professor of urban and regional planning at the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, is one of the most prominent voices, saying that the time has arrived. She came to Michigan 29 years ago from the University of Minnesota, in part because U-M was so close to Detroit.

“I found to my surprise that there wasn’t that much connection,” Dewar says. However, the relationship between the University and the city has developed over the years, in part because of the efforts by Dewar and her colleagues.

The idea for a Detroit School began in 2011, with a proposal to hire a group of new faculty members whose research would focus on Detroit. Since then, four Detroit-focused positions have been created: one in the Urban and Regional Studies Planning Program in the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, one in the Department of Sociology, one in the School of Social Work, and a shared position between LSA’s Department of Afroamerican and African Studies and the Residential College.

Also, a regular Detroit School lecture series focuses on urban issues. Dewar adds that Ph.D. students from all over the world who study Detroit have presented their research to audiences at Michigan. Those presentations have linked the University with others in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and China who are interested in scholarly research on Detroit. Dewar says the Detroit School could be a clearinghouse for the multiple programs at U-M focused on the city.

“There’s so much going on across the campus, and it’s hard to get a handle on it,” Dewar says. Beyond that, the Detroit School wants to be a central location for research taking place into issues that affect the country, such as the impact of mortgage foreclosures and the creation of urban land banks.

“We’re doing all this work in the neighborhoods,” she says. “What can inform urban studies and theory everywhere?”

The main obstacle to the creation of the Detroit School, says Dewar, is the time required to bring all the pieces together. Moreover, she thinks it needs a high-level champion willing to keep pushing. But she believes the impact can be significant.

“There is a lot of change on the ground. Not due to us, but due to the partnerships” with academics elsewhere, Dewar says. “Those who are studying Detroit have so many ideas, and energy, and they want to contribute.”

It’s overshadowed by better-known neighborhoods such as Indian Village, Corktown, and Boston-Edison, but Cody Rouge, on the west side of Detroit, has become the focus of a University program that is partnering with other organizations to improve residents’ health awareness and lower the cost of delivering health care.

The neighborhood has both problems and promise. In addition to blight and a large number of unoccupied homes, residents have many health care concerns, including diabetes and heart disease.

U-M Professor Michele Heisler and her team from the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation are helping to spearhead the new project to train community health workers—lay health workers, often from the same community, who have strong communication skills. These workers will reach out to residents who have enrolled in Medicaid but are still relying on emergency departments for their care, have been hospitalized for conditions that can be treated with good primary care, or have not accessed primary care in the previous 24 months. The health workers will assess these residents’ health needs and goals, and work with them to develop an individualized plan.

“There are resources in Detroit,” says Heisler. “This involves linking people to them.” The team also will evaluate the program’s impact on health care use, costs, and resident satisfaction.

The U-M institute is working with the Detroit Health Department, Medicaid health plans, and the Joy-Southfield Community Development Corporation.

“We would love for this to be a model all over the city of Detroit,” Heisler says. She feels strongly that the University should be involved in such programs because of its proximity to the city.

“Of course, U-M should be in Detroit, because it’s in our neighborhood,” Heisler says. “I don’t feel Ann Arbor can truly be great unless we make Detroit great.”

Micheline Maynard is a regular contributor to Michigan Alumnus and recently wrote about diversity on campus. She is the former Detroit bureau chief for the New York Times.