When Pride Prevailed

•

ILLUSTRATIONS BY VICTORIA O’BRIEN

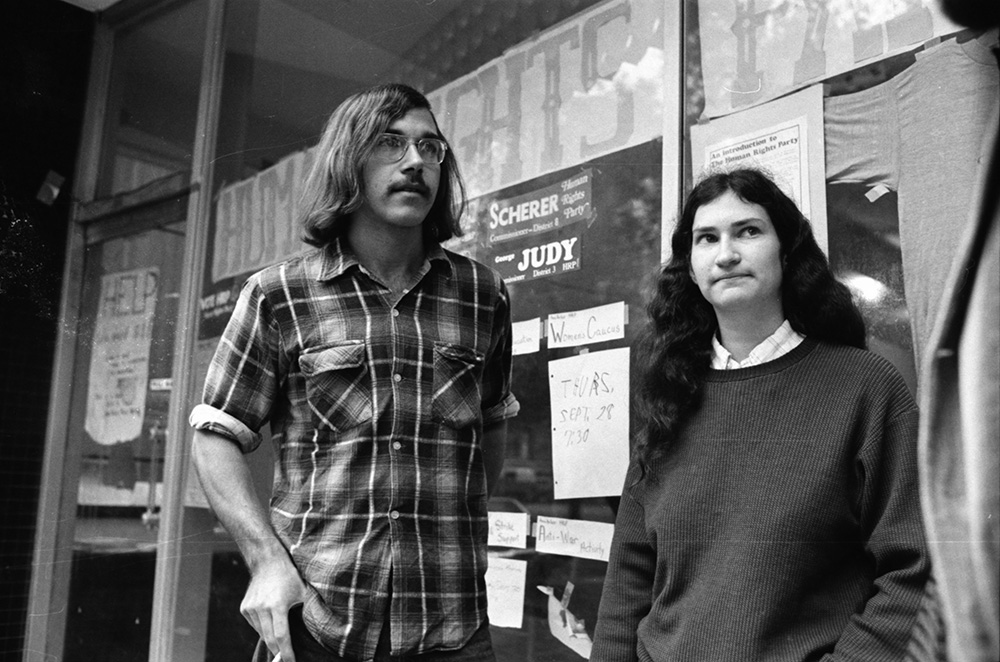

The night before Nancy Wechsler, ’71, and Jerry DeGrieck, ’80, made history, Wechsler was kicked out of an Ann Arbor bar.

She was at the Rubaiyat, dancing and enjoying the evening with a group of lesbian friends. Though the Rubaiyat eventually became a beloved gay bar, on October 14, 1973, the women were ejected for slow dancing and kissing — discriminated against for being gay.

And it was Wechsler who called the police.

“I ended up calling the police and asked them to explain to the owner that this was against the Human Rights Ordinance. And the policemen did not know what I was talking about,” Wechsler says.

The Human Rights Ordinance, which included protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation, was passed in July 1972 by the Ann Arbor City Council, which included Wechsler, representing the 2nd Ward, and DeGrieck, representing the 1st Ward. However, it seemed the local police had received no training or information about the ordinance, despite more than a dozen complaints being filed with the Ann Arbor Human Rights Commission.

“The next day, [Walter] Krasny, the chief of police at the time, came to city council to give his yearly report. Jerry and I used that opportunity to question him about how the Human Rights Ordinance wasn’t being enforced,” Wechsler says. “We both came out at that meeting.”

On October 15, 1973, Wechsler and DeGrieck became the first openly gay elected officials in U.S. history. The following year, Kathy Kozachenko, ’11, would become the first person in the country to run as openly gay and be elected.

Each of their political careers began at the University of Michigan.

Photo courtesy of The Ann Arbor News

The Draw of Ann Arbor

In the late 1960s, U-M’s campus was alight with political activism, student protests, strikes, and community engagement.

It’s what drew the three to U-M: Kozachenko, who wanted to go to the “most radical campus” with in-state tuition, Wechsler, who began her college years at the more conservative Colorado College in Colorado Springs before transferring as a sophomore, and DeGrieck, who was looking to escape the entirely white and Christian community in which he was raised.

Each was interested in politics in their own way: Wechsler’s parents were very politically engaged, while Kozachenko’s rarely talked about politics. DeGrieck knew he was “different” and decided to express himself through activism from the time he was about 10 years old. They each got involved with politics shortly after arriving on campus, where the atmosphere of student activism continued to grow.

U-M held the first-ever teach-in protest in 1965 in opposition to the Vietnam War, Black Action Movement demonstrations began after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968, and the Gay Liberation Movement gained momentum in Ann Arbor in 1970, among a host of other student protests. DeGrieck remembers demonstrations for student power, increased Black student enrollment, tenants’ rights, and many other issues. One of the first major demonstrations he participated in was for the addition of a student-run bookstore to compete with private companies’ staggering prices. Later, during Kozachenko’s campaign, her political opponent would be “greatly chastised” for eating non-union lettuce while claiming to support the United Farm Workers.

“It was a big scandal in the campaign,” Kozachenko remembers. “Not that that’s hugely radical, but it shows you what the consciousness was, what the level was that this was seen as a political act of betrayal.”

Wechsler, DeGrieck, and Kozachenko met through political work and eventually affiliated with the Human Rights Party (HRP), a radical socialist third-party organization. HRP platform information, published in the Ann Arbor Sun, described the party as one that “seeks a society in which all people are able to grow fully, free from discrimination and oppression, and in which everyone shares equitably in the wealth of the country and the decisions which affect their lives,” arguing that “The Democrats and Republicans cannot create real change because they represent the interests of business and the rich.”

Kozachenko says HRP “felt that elections were one means to change to a more equitable society.”

“The way I explain it now, we had politics similar to those of Bernie Sanders. We were not totally devoted to elections. So we did strike support, we supported the United Farm Workers boycott, and we did work with welfare reform, we were allies for racial justice. … What could we do to spread our ideas, to gain momentum, and be a voice for change, for positive change, for economic justice, social justice,” she says.

HRP believed that prisons should be replaced with rehabilitation centers, laws against homosexuality and prostitution should be repealed, and courses on “minority cultures” should be offered in schools. They championed transgender rights, decades before transgender people would earn legal protections in Michigan.

While many of these platforms may have seemed extremely progressive for the time, Kozachenko says it was all part of the social and political climate in Ann Arbor.

“In towns a half-hour away, our ideas may have seemed very radical, but within the confines of the campus community and in Ann Arbor, it was the milieu.”

The First Victories

Wechsler had graduated from U-M before running as an HRP candidate for Ann Arbor City Council but, one course shy of graduation, DeGrieck elected to delay the completion of his degree until after his city council term.

“When I was at the University of Michigan, I majored more in political activism than I did in classes in terms of what I learned,” DeGrieck jokes, clarifying that he had many wonderful professors but was primarily focused on political activism.

Wechsler wasn’t quite sure she was a lesbian when she decided to run, though she’d been very involved with the Gay Liberation Movement on campus. She consulted an openly gay friend, Jim Toy, MSW’81 — one of the co-founders of the Ann Arbor Gay Liberation Front and the Spectrum Center. Wechsler was unsure if she should run as a lesbian, and remembers Toy suggesting that, pragmatically, she might have a better chance of winning if she didn’t run as openly gay.

“In a way, part of me wishes he encouraged me to just run as an openly gay candidate, but that’s okay,” Wechsler says, adding that she and Toy never revisited this interaction before he died in 2022, but she remembers how supportive he was of her candidacy.

She was hesitant about running and urged DeGrieck to run for the 1st Ward alongside her.

“I trusted him, and he wasn’t in it for the glamor or anything. He wasn’t like a politician. He was like a political activist,” she says. DeGrieck was not yet out and Wechsler says she didn’t know at the time that he was also gay.

He was, however, hoping to come out as gay soon. DeGrieck went to student health services and saw a psychiatrist, who he hoped would help him find a way to personally deal with his homosexuality and be openly gay.

“I expressly said, ‘I want to come out and I want help.’ And after two or three sessions, she said she couldn’t help me — if I wanted to ‘remain straight,’ she would help me. But she couldn’t help me come out because, in those days, it was still considered a psychological disorder,” he says.

DeGrieck had run for city council the year prior in the 2nd Ward as part of the Radical Independent Party (RIP) and, despite ardent canvassing and debates, did not gain much momentum, collecting only 161 votes as a write-in candidate.

Looking for greater recognition, RIP decided to affiliate with HRP and form the Human Rights Party of Ann Arbor. In 1972, after collecting 21,000 petition signatures, HRP candidates appeared on the ballot in all five wards.

HRP was hopeful for Wechsler to win in the 2nd Ward — widely known as the student ward — but was not holding their breath for much more. Even DeGrieck didn’t think he would win the 1st Ward, but that didn’t prevent him from trying.

“We ran an incredible campaign, I think, that year. We were very creative, we had a great office, and we did a hell of a lot of canvassing, going door-to-door,” DeGrieck says, adding that the political movements in Ann Arbor of the time coincided with their campaigns and likely aided in their efforts. In January, the 18-year-old voting age went into effect and HRP hoped to gain the support of young voters, who made up about one-third of Ann Arbor residents.

The night of the election, DeGrieck remembers it quickly became clear that Wechsler would win the 2nd Ward. His own victory became apparent soon after.

“Jerry’s election in a ward that was not just a student ward was exhilarating,” Kozachenko says. The wins demonstrated HRP’s alignment with community politics and foreshadowed a promising term for the new council members.

Photo courtesy of the Ann Arbor News

That year, there were four Democrats, five Republicans, and two members of HRP on the city council and, because of the composition, neither Democrats nor Republicans could pass legislation without collaboration with HRP.

In 1972, the Ann Arbor City Council passed a ban on non-returnable bottles, a shift of $600,000 of revenue-sharing funds to child and health care, and the headline-making $5 marijuana fine. They also passed the Human Rights Ordinance, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, student status, marital status, and sexual preference, and the “Lesbian-Gay Pride Week Proclamation” — the first-ever gay pride proclamation to be passed by a U.S. governing body. Toy co-authored both pieces of legislation.

City council meetings were televised and drew abundant public participation, so when Wechsler and DeGrieck came out in October of the following year, it was to a significant crowd.

DeGrieck says he was ready because he was “finally” in a relationship with a man and the city council discussion about the Human Rights Ordinance was a perfect opportunity.

“Nancy and I could no longer talk about the rights of ‘those people over there’ because we were one of them,” DeGrieck says.

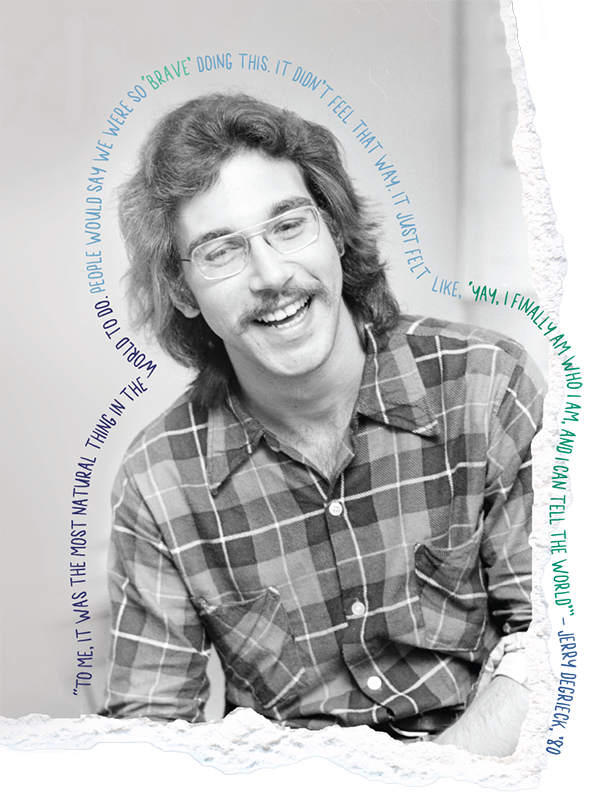

But for both Wechsler and DeGrieck, coming out was a relief.

“To me, it was the most natural thing in the world to do. People would say we were so ‘brave’ doing this. It didn’t feel that way. It just felt like, ‘Yay, I finally am who I am, and I can tell the world,’” DeGrieck says.

Wechsler agrees.

“I felt good. It was like a relief. Jerry and I both felt like we had been waiting on some opportunity to publicly come out and it seemed like a good way to do it,” she says.

What they didn’t know at the time was they were the first openly gay elected officials in U.S. history. Wechsler had an inkling, because she “hadn’t heard of anybody else.” DeGrieck realized it some days later.

Though their coming out was largely a celebration, some things did change.

“This was at a time when a lot of people would not come out and felt that they couldn’t come out, and so people didn’t know that many of the people that they probably interacted with were ‘sexual minorities’ because people were not out. And here we had two very public people who, some folks at least, thought highly of and respected, and suddenly they had to deal with the fact that we were gay,” DeGrieck says. “Sexual minorities” was a term coined in the late 1960s, frequently used in reference to members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Wechsler continued to receive hate mail.

“I got a lot of hate mail when I was on city council for being like a ‘lefty,’ and antisemitic stuff for being Jewish. And then when I came out, the hate mail continued. Not only was I a leftist and was Jewish, but I was queer,” she says.

Republicans gained the majority in 1973 and one year later, DeGrieck and Wechsler decided not to run again.

DeGrieck and Wechsler both hold strong beliefs that their time as city council members was not about them as individuals, but was about representing the political beliefs and aspirations of their communities.

“We talked to a lot of people. We got a lot of people engaged. We got people to come to city council, and demonstrate, and speak, and get out on the picket line, and show up for each other. I’m definitely proud of that. I’m proud of what HRP did and proud that I was a part of that. I certainly hope that things are better in Ann Arbor, at the University of Michigan because of what we did,” Wechsler says.

Another Win

As Wechsler and DeGrieck planned to leave the city council, and the 1973 HRP candidates did not win a seat, Kozachenko refused to let their momentum die out.

“I thought that if the Human Rights Party was going to survive and be viable as a vehicle to both talk about social change and actualize social justice in whatever way we could, it was important we have somebody on city council. It gave us legitimacy. It gave us a voice. It gave us a way to reach people outside of the college campus. I felt it was important for us to maintain a seat on city council,” Kozachenko says. “So I ran.”

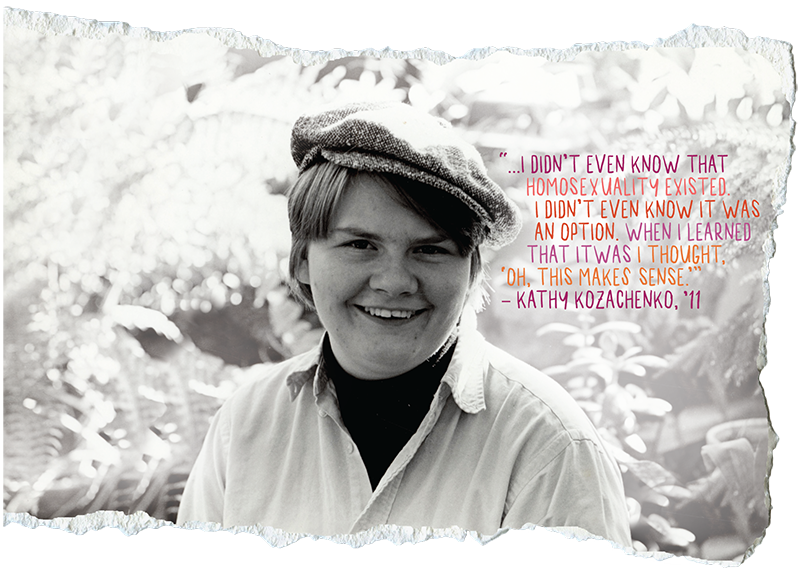

Kozachenko came out in her first year at U-M.

“I was — I don’t want to say sheltered, but I was something because I didn’t even know that homosexuality existed. I didn’t even know it was an option. When I learned that it was, I thought, ‘Oh, this makes sense,’” she says.

Candidates don’t make major decisions about their campaigns on their own, but Kozachenko’s campaign manager and HRP supported her running as an openly gay candidate.

“It was a part of who I was, but it was also a part of who HRP was in terms of breaking down stereotypes and gender roles, which, back then, it was a radical thing to do because the gender roles were very rigid.”

Kozachenko won by a narrow 52-vote margin and became the first openly gay person to be elected to public office in the U.S. Her title was frequently misattributed to Harvey Milk — the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California — for most of the last 50 years, but Kozachenko says this has never bothered her.

“I think because we were from a third party and from Ann Arbor, we didn’t get the kind of publicity that Harvey Milk or Elaine Noble got,” Wechsler says. Elaine Noble was the first openly lesbian or gay candidate elected to a state legislature.

Kozachenko was the only member of HRP on the city council. During her first year, she faced a Republican majority and struggled to get anything passed. In her second year, she was positioned as a swing vote and largely forced to vote with the Democrats.

“I had a whole different experience than Nancy and Jerry. I was there by myself,” Kozachenko says.

Though she wasn’t able to pass as much HRP-supported legislation as her predecessors, Kozachenko still left her mark on other city council members.

The Republicans began city council meetings with an invocation and Kozachenko remembers asking to lead the invocation so she could read a poem she had written.

She asked all the women to stand and all the men to remain seated. The Republican men remained standing as Kozachenko began her poem, “Invocation to Inez Garcia.” Garcia was a California woman who, the day prior, had been sentenced to five years in prison for killing her rapist. The poem was a protest statement against the mistreatment and discrimination of women.

“I had gone four or five lines into the poem, and the Republican men sat down in respect. It was a powerful moment,” Kozachenko says. “I felt like it was a communication, that I wasn’t just some smartass that was, for whatever inconsequential reason or radical reason, trying to have all the women stand up. That was a very moving moment for me and my city council career.”

After her two-year term, Kozachenko set her sights elsewhere and decided not to run again. She was one requirement shy of graduating when she left U-M, where she was majoring in creative writing, and finished her degree in 2011.

“I did not feel that being on the city council of Ann Arbor, Michigan, was the most effective way for me to use my time and energy to work for social change and social justice,” she says.

HRP continued to lose ground in Ann Arbor after Kozachenko’s departure. By 1977, HRP identified with the Socialist Party of Michigan and the Ann Arbor City Council has been almost entirely comprised of Democratic and Republican council members ever since.

Continued Political Work

Today, Wechsler lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, DeGrieck in Seattle, and Kozachenko in Pittsburgh. They each had partners and became parents — something they never thought would be in their futures.

“The way that life was portrayed for people who were homosexual was miserable,” DeGrieck says, remembering what he was taught growing up. “And so I thought I might be doomed to this miserable life.”

DeGrieck feels “blessed and honored” to have been able to have two children with his life partner of 26 years and the children’s lesbian moms. He has two grandchildren now as well.

“Having my son was just literally my dream come true,” says Kozachenko, whose son, Justin, now resides nearby in Pittsburgh. Wechsler’s daughter, Ella, is also in Cambridge.

They each continued to work in politics: DeGrieck supported political movements in Seattle and worked in local government throughout his career in many leadership positions including in public health, education, and human services; Wechsler wrote and photographed for the Gay Community News in Boston, among other publications, and worked at political organizations including the Resist Foundation and the American Friends Service Committee; and Kozachenko went on to work on political campaigns and as a health care professional, in addition to her volunteer work for voter registration, teaching English as a second language, and more. She is also currently writing a memoir.

All three are concerned about the current backlash against LGBTQ+ rights and stress the importance of political engagement.

“I would encourage students, to be aware, to be active — however they want to be — and to vote,” DeGrieck says.

As part of Ann Arbor’s bicentennial celebrations and 50 years after her election, the city plans to erect a statue of Kozachenko in front of city hall.

“Kathy Kozachenko is a trailblazer in queer history, and more broadly the history of our city and nation,” says Ann Arbor city council member and mayor pro tem Travis Radina, ’08. Radina is an openly gay city council member representing the 3rd Ward. “Her election, along with Nancy Wechsler and Jerry DeGrieck publicly coming out while serving, helped pave the way for me and the thousands of other LGBTQ elected officials in the last 50 years — including the at least 1,185 LGBTQ+ elected officials currently serving in the United States today. They redefined what was possible for LGBTQ people seeking to run for office, and they demonstrated that LGBTQ leaders deserve a seat at the table.”

The Michigan Historical Commission has also granted Ann Arbor permission to establish an official historical marker outside city hall, which will share the city’s LGBTQ+ history and human rights efforts, as well as Wechsler, DeGrieck, and Kozachenko’s monumental victories.

“By commissioning a statue of Kathy, and dedicating a state historical marker — the first in Michigan focused on LGBTQ history — celebrating the impact and legacies of Kathy, Nancy, and Jerry, it is my hope that LGBTQ young people will soon be able to come to Ann Arbor City Hall and see themselves as integral to our community’s success — as people who are valued, respected and celebrated, and who can someday earn their own place in our history books,” Radina says.

KATHERINE FIORILLO is the editor of Michigan Alum.