Everyone possesses a certain object, whether treasure or trinket, that strikes an emotional chord. We asked alumni to share one object that brings them joy, magic, and meaning.

“He taught me to hunt and how to throw a knife so it would stick in the wall. But he also taught me to take things in stride.”

Jerry Murrell, ’66 • founder, Five Guys restaurants

This axe hangs in my garage in D.C. It’s ugly, useless junk, I guess, but it means a lot to me. It belonged to my grandfather, who got it in the 1920s when he went to live in the lumber camps as a young man. He made so much money as a cook’s helper that he was able to buy a 40-acre farm in northern Michigan with cash.

I used to go to his farm as a kid. It was cold as hell up there, and we were constantly cutting wood. It always amazed me how he’d take that old axe and go through a sapling—boom!—just like that. He taught me to hunt and how to throw a knife so it would stick in the wall. But he also taught me to take things in stride. I remember one time when blight killed 35 of his 40 acres of potatoes.

He’s standing there looking out over the farm, and I mention something about how terrible it is. He turns to me and says, “Well, the price of potatoes is going to be high this year.” I think about that all the time. When the Wall Street Journal calls me and asks, “What are you gonna do about the price of hamburger going up?” I say, “Is it going up just for me?” I learned a lot from Grandpa’s outlook: If it’s everybody’s problem, it’s not really a problem.

So one day, maybe 20 years after he died, I was in Michigan from D.C., and I went back to Grandpa’s farm and into the garage and took the axe. It’s the only thing I wanted.

“It’s a humble-looking item, but there’s wisdom within it.”

Professor Shelly Schreier, ’83, MA’85, PhD’89 • lecturer in the U-M Department of Psychology

I have a pink, 6-by-9 inch steno pad that belonged to my grandmother. It has 100 pages, and it cost 49 cents. It’s full of tiny thoughts that she cut out from newspapers, sayings that she heard and wrote down—like “Blessed are those who give without remembering and take without forgetting”—quotes from Erma Bombeck and Dear Abby but also Mahatma Gandhi, and things she wished she’d said.

My grandmother was born 100 years ago and immigrated to this country. She wasn’t able to have as much formal education as she would have wished for—she left school after eighth grade and worked in the family grocery store in Detroit—but she was so thoughtful and so desperately wanted to learn and think. She worked very hard throughout her life to be an educated person. At some point, she told me that one of her motivations for writing things down was that she always wanted to have the right words at hand.

I treasure this notebook. It’s a humble-looking item, but there’s wisdom within it. It’s a connection with family, to the love of learning, to the importance of words. It taught me how important it is to ask questions, to want to know. I value formal education, and I carry my Maize and Blue heritage with pride. But, as an educator, I also believe that learning takes place throughout our lives and that we must be open to learning in unexpected places and from different people—even Dear Abby.

There are maybe 10 or 15 pages that my grandmother didn’t fill in as well as some loose newspaper clippings. After she passed, I glued in a few of those articles.

“It’s the thing that I’ve laid eyes on for the greatest portion of my life.”

Chris Van Allsburg, ’72, HLHD’12 • Caldecott award-winning author and illustrator of “Jumanji,” “Polar Express,” and “The Misadventures of Sweetie Pie”

I made this odd little creature when I was 7 years old. It’s my interpretation of a duck-billed platypus. I gave it hair—it appears to have a crew cut—a wistful look, a belly button.

I had a pretty good art teacher back then, and we did projects with tongue depressors and popsicle sticks and made ashtrays out of clay. I’m sure I brought all of that stuff home and presented them to my mom. But this platypus must have captured her fancy because she gave it a place of prominence over the kitchen sink. Later, when we moved to another house, she placed it over the kitchen sink there, too. She had it in that spot for over 20 years.

I’m pretty sure I know why the platypus interested me then: It’s the rare mammal that lays eggs. I had an interest in the unconventional and was fascinated by strange-but-true stories and the paranormal.

I don’t know if it’s disrespectful to call the duck-billed platypus “paranormal,” but it was inexplicable and became a touchstone for my artistic creations later.

Sometimes, I look at the little platypus and I’m amused by it. It holds the memory that my mother developed an affection for it and took care of it. Add to that that it’s something I made and that I went on to get my degree in sculpture at Michigan. But at some point, it also became the oldest thing I owned. It’s the thing that I’ve laid eyes on for the greatest portion of my life. I made it in 1956, and the fact that I can still lay eyes on it all these years later makes me feel like I’m looking at old family photos: It’s a sobering sort of evidence of how quickly your life goes by.

I don’t have a shelf over the sink now, but it’s in my kitchen—on a little shelf over the stove.

“The water’s coming in through the walls, through every crack.”

Nat Rosenthal, ’91 • consulting executive

We did OK through the first days of Hurricane Harvey. We fought it. But then they released the reservoirs, and it took us a while to realize what was really happening. We fought that night, too, but at one point it was over: The water came in all at once, from all sides of the house. Outside, it was dead quiet. No rain. No cars. No power. No movement anywhere. But the water came in through the walls, through every crack.

That night, I got a text from my son:

– How are you doing?

– Fine.

– Are the Magic cards safe?

Yes, the Magic cards were safe. They were the first things I’d grabbed from the office downstairs. My whole life was about to get flooded—there were photo albums, rugs, books down there—but I’d gathered the cards from the floor and brought them upstairs. It took four trips because there are 3,000 or 4,000 of them in three-ring binders and 2-foot-long boxes. My son was half-kidding—but only half. He wanted to know. Those cards are our connection.

I started playing Magic: The Gathering with a few guys in ’95, when I was studying for my MBA and getting sober. We stopped playing after a few years, but I kept my cards, kept them through my first marriage. And when I got divorced, I brought them with me. I remember thinking, “Maybe my son will be a little nerdy, too, and I’ll get to share this with him.” When he was young, he liked the pictures. But as he got older, he liked that each game had an infinite number of possibilities. Being a divorced dad, I saw Ethan every other weekend and I was looking for ways to connect with him. On Friday nights, we’d go to gaming shops with names like Asgard and they’d have tournaments. We’d get clobbered, but we didn’t care—I was spending time with Ethan.

They don’t make a lot of those cards anymore, and they’re worth quite a bit. But I keep them because my son likes them, because we have that connection.

“At first, the blanket symbolized my family back home and the distance. But later it came to encapsulate the entire Michigan experience.”

Demario Longmire, ’17 • former Alumni Association LEAD Scholar, Washington AIDS Partnership Health Corps fellow and program coordinator at Helping Individual People Survive

I was raised in Muskegon, Michigan, a factory town close to Lake Michigan and, for me, very conservative. I found it small and hard to live there. My family didn’t know much about college—I’m the oldest of nine kids and a first-generation college student—and even though Ann Arbor was only 2 1/2 hours away, I arrived without a sense of what my next four years would look like.

But while my family didn’t know much about college, they knew community and love. This quilt was a high school graduation gift from a friend of the family who makes them. When I got it, I was just starting to see myself as a Wolverine, trying to picture myself in the new community. This was one of the first times that it set in that this was real, that I would be leaving for college, that I was going to be sleeping somewhere else, far away. When I got to school, I was sort of nervous and I remember thinking that all the other kids knew what was going on. I put the blanket on my bed Day One.

At first, the blanket symbolized my family back home and the distance. But later it came to encapsulate my entire Michigan experience: the a cappella and performance communities I became part of, the social justice work I did, the other LEAD Scholars I got to know, and the financial investment that Michigan made in me. (For more on LEAD Scholars, see here.) Now, a year out of school, the blanket has expanded in its meaning—and, in an oddly poetic way, the squares have stretched as well. I see it as a symbol of my journey, where I’ve been, who was part of it, and where I can go. It feels like a part of me now.

“The family was forced to sell pretty much everything they owned. But they kept this necklace.”

Lisa Franklin, ’92 • clinical social worker

My grandmother Hedy was a bit of a rebel: During the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, all Jews were commanded to stay inside their homes. But at 14, she snuck out of the house and made her way to the stadium because she just had to see Jesse Owens run. If she’d been caught, the whole family could have been killed.

They were living in Berlin, where Hedy’s father—my great-grandfather Hans—was a prominent businessman and a decorated World War I veteran. All through Hitler’s rise to power, Hans remained convinced that he’d be overthrown or assassinated, so he refused to leave Germany. But as things grew worse—their bank accounts were frozen, they could buy food only a few times a week—the family was forced to sell pretty much everything they owned. But they kept this necklace. It was something my great-grandmother really treasured, not because it had monetary value—it didn’t—but because Hans had managed to buy it for her during a down year in his business. In fact, because it wasn’t valuable, it was one of the few things they didn’t sell.

On Nov. 9, 1938—Kristallnacht—Hans was arrested and sent to a concentration camp. Four months later, incredibly, the Nazis decided to release all decorated World War I vets. At that point, Hans conceded that they needed to leave Germany. He contacted a group of men he had commanded during the war who, in exchange for the deed to his apartment and access to his bank accounts, arranged passports and plane tickets for the whole family.

Passage was extremely risky, and they weren’t supposed to take anything with them. But Hedy sewed the necklace into the hem of her skirt because she knew how much her mother loved it, and when they were finally safe she presented it to her.

Eventually, my great-grandmother gave the necklace to Hedy, starting a tradition of handing it down to the oldest daughter. Hedy gave it to my mom, who then gave it to me just before my wedding. Someday, I’ll give it to my oldest daughter. The necklace has always meant a lot to me. But it wasn’t until recently, with all the debate about immigration, that I started to appreciate its significance on a deeper level: My family didn’t die in the Holocaust because they were welcomed here. The necklace is probably the only physical object I care about—and it now holds more meaning for me than ever.

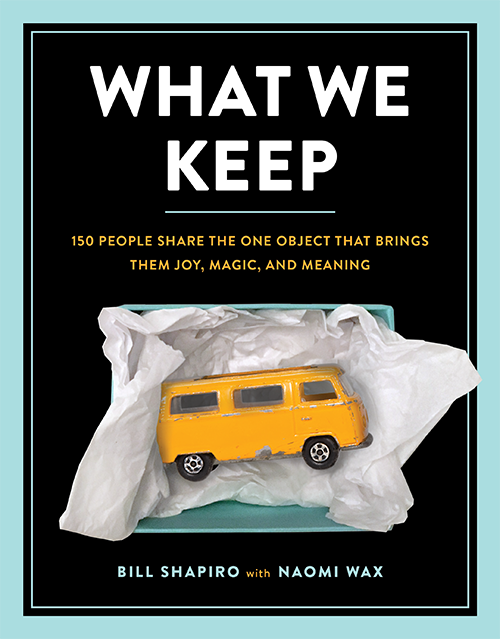

It started rather randomly at a garage sale. Authors Bill Shapiro and Naomi Wax, ’87, happened upon an old locket bearing the inscription “My Love Forever.” What was the story behind that seemingly sentimental object, and why would it be for sale at the end of a driveway? From that locket came the idea for a book about the objects that hold special meaning for us and the often-surprising stories behind them. In this article, we share the stories of U-M alumni and their treasured objects. In their new book, “What We Keep” (Running Press, 2018), the authors share stories of people across the country, from business leaders Mark Cuban and Melinda Gates to award-winning writers Ta-Nehisi Coates and Cheryl Strayed, from hairdressers and dishwashers to cloistered nuns and convicted counterfeiters.

It started rather randomly at a garage sale. Authors Bill Shapiro and Naomi Wax, ’87, happened upon an old locket bearing the inscription “My Love Forever.” What was the story behind that seemingly sentimental object, and why would it be for sale at the end of a driveway? From that locket came the idea for a book about the objects that hold special meaning for us and the often-surprising stories behind them. In this article, we share the stories of U-M alumni and their treasured objects. In their new book, “What We Keep” (Running Press, 2018), the authors share stories of people across the country, from business leaders Mark Cuban and Melinda Gates to award-winning writers Ta-Nehisi Coates and Cheryl Strayed, from hairdressers and dishwashers to cloistered nuns and convicted counterfeiters.

Naomi Wax, ’87, writes for the Ford Foundation and other social justice organizations; Bill Shapiro is the editor of Getty Images FOTO and the former editor-in-chief of LIFE magazine.

Notebook, quilt, and necklace photos by Bob Foran | Platypus photo by Cynthia August | Magic cards photo by Brian Vogel