In the 1960s, Ann Arbor had it all: JFK, MLK, LBJ, and the CIA; hawks, doves, panthers, and pigs; sit-ins, teach-ins, lock-ins, and sleep-ins; radicals on the left, reactionaries on the right, and a great mass of mystified in the middle.

Back then, Ann Arbor was a wild and wooly place that regularly made national headlines—not as one of the best places to retire or raise kids, but as a key center of political and cultural revolution that rivaled the better-known Berkeley, Madison, and Columbia.

“There were some left-wing radicals in Ann Arbor in the early 20th century and more of them during the 1930s,” says Howard Brick, ’75, MA’76, PhD’83, U-M professor of history. “But it wasn’t until the 1960s that the city and the University became a real crucible of protest—that is, when the heritage of Detroit’s vigorous unionism met the new, mass constituency of students in the age of postwar collegiate expansion.”

That combination made Ann Arbor the home of a unique political creativity that gave birth to a host of influential groups and ideas, Brick adds. “Of course, there were other such places, too, but Ann Arbor in the 1960s was a key member of the renowned roster of locales which fostered innovations in dissenting thought, movement organizing, and cultural transformation.”

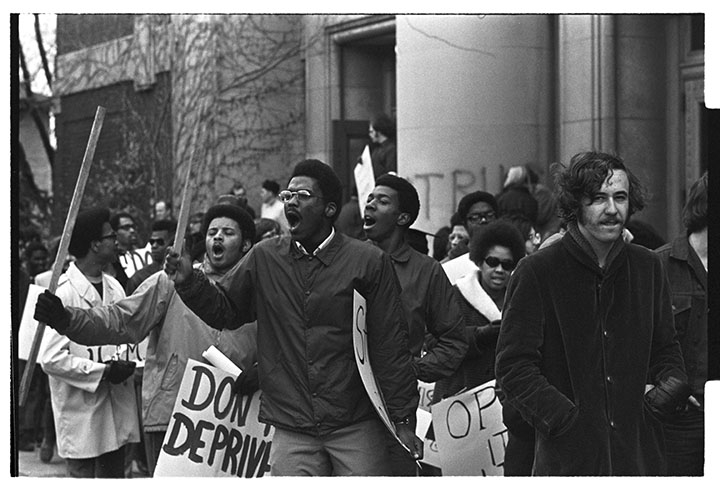

Below: The Black Action Movement led a massive strike in early 1970. Among the demands was a 10 percent enrollment of African-Americans by the 1973-74 academic year.

By most accounts, the ’60s began—appropriately enough—on Feb. 1, 1960, when four black students in Greensboro, N.C., sat down at a racially segregated lunch counter in the local Woolworth five-and-dime. Lunch counter sit-ins spread quickly throughout the South, and activists in the North, eager to lend their support, began protesting at local outlets of the chain stores being targeted by Southern demonstrators. In Ann Arbor, a coalition of students and townspeople picketed Kresge and Woolworth stores, soon expanding their protests to include hometown businesses—clothiers, restaurants, recreational facilities—that discriminated against African-Americans.

Such activities weren’t well-received in many quarters—the picketers were given no coverage in the Ann Arbor News, had little if any support in city government, and were regularly harassed by unsympathetic students, citizenry, and police. Nevertheless, the protests continued, every Saturday, for nearly nine months.

The pickets brought the city’s people of conscience together in a way that hadn’t happened before. Two months after the start of the Ann Arbor picketing, a providentially timed conference on civil rights held at the University gave a sudden infusion of energy to a new youth activist group called Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Ultimately, SDS would become the biggest and most influential radical organization of the ’60s.

But it was still small and relatively unknown in 1960 and might have remained as such if not for the tireless organizational efforts of its first president, U-M undergrad Alan Haber, ’65. It was Haber who almost single-handedly turned a loose confederation of young mavericks into a cohesive national group dedicated—at least at first—to the ideal of participatory democracy. Ann Arbor played host to most of the SDS leadership during the early years of the ’60s. Tom Hayden, ’61, Rennie Davis, ’63-65, Todd Gitlin, ’66, Carl Oglesby, ’62, and others lived and worked in town, usually while attending the University.

The civil rights struggle occupied center stage during the first half of the decade, and although most of the action took place elsewhere, Michigan activists contributed. More than a few followed Hayden’s example and went south to join the struggle—they included Walter Bergman, ’23-’25, who was left permanently paralyzed after being attacked and beaten during the Freedom Rides of 1961. Others stayed home and organized support groups such as Friends of SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, based in the South) or gathered funds and material goods to contribute to the cause.

Ann Arbor also provided an important platform from which national civil rights leaders—Martin Luther King Jr., Malcom X, Bob Moses, Stokely Carmichael, Julian Bond—could air their views. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson gave the University’s commencement address, choosing that moment to share with the world his vision of a Great Society free from poverty and racial injustice.

The city itself was not free of bigotry, but in the 1960s there appeared a swift and determined response rather than a sweeping under the rug as usually happened in the past. In 1961, for example, the University’s dean of women resigned under pressure from student groups who accused her of discriminatory practices. Also, a protracted struggle ensued for a local fair-housing ordinance. It lasted most of the decade and included regular picketing of city hall plus a series of sit-ins that resulted in the arrest of more than 60 students, faculty, and townspeople.

As with the rest of the country, the advent of the ’60s brought Ann Arbor’s small but dedicated pacifist element out of its shell. Particularly significant were the efforts of U-M students and faculty to lay the groundwork for the Peace Corps following a speech made on the steps of the Michigan Union by Sen. John F. Kennedy during the 1960 presidential campaign. Also of note were the solemn demonstrations made by Ann Arbor Women for Peace and student organizations such as SDS against atomic testing and the nuclear arms race—sentiments that weren’t easy to express in the early 1960s. At one such gathering during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Hayden and others were pelted with eggs and rocks.

By mid-decade, however, the peace movement had gathered considerably more support. Instead of the Cold War with Russia, the focus was the hot war in Vietnam. Early in 1965, a group of outraged Michigan faculty announced a teaching strike to protest the massive U.S. bombing campaign recently launched against Hanoi. But after being threatened with disciplinary action if they canceled classes, the rebellious professors adopted a different approach. Instead of teaching less, they would teach more and hold extracurricular sessions on Vietnam all through the night. Thus was born the “teach-in”—an idea that spread like wildfire to hundreds of campuses across the country and became the protest movement’s key educational instrument for many years to come.

“It just mushroomed,” Todd Gitlin, MA’66, told Michigan Alumnus in “Teach Your Children Well,” a spring 2015 article about the teach-in. “I don’t know the statistics, but all of a sudden there were teach-ins happening everywhere. Berkeley put on a huge two-day spectacle, which drew thousands of people. Very quickly, with so many faculty taking part, it became clear that the anti-war movement was not simply a student movement.”

As the fighting in Southeast Asia continued to escalate, anti-war demonstrations became more numerous and more disruptive. During homecoming weekend of 1965, 39 U-M students and several junior faculty were arrested for sitting in at the Ann Arbor draft board—the country’s first incidence of mass civil disobedience directed against the Vietnam War. A number of the male arrestees lost their student deferments and were reclassified 1-A, making them available for immediate induction into the armed forces. (After a national outcry, most had their deferments restored; none ended up being drafted.)

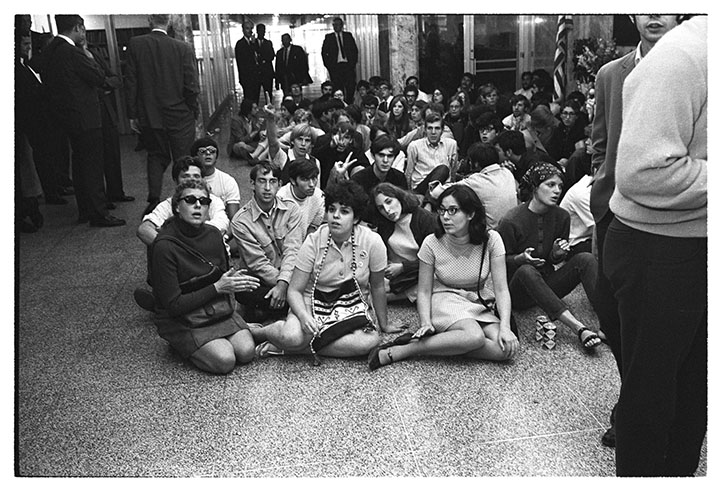

In the months to come, anti-war activists would hold sit-ins to protest the University’s classified military research. Defense-industry and CIA recruiters were blocked from entering or locked in their offices. Hawkish politicians such as Rep. Gerald Ford, ’35, were heckled, and city ballot referendums were proposed condemning the war. There were peace marches, draft-card burnings, tax boycotts, almost-daily demonstrations and rallies on the Diag, and regular bus trips to Washington, D.C.

But the ’60s weren’t just about the war, and obstreperous Michigan students found plenty of other issues to occupy their non-class time. In 1966, the University’s ill-advised ban on sit-ins resulted (naturally) in a series of retaliatory sit-ins. By the end of the decade, sustained opposition to in loco parentis—the university as parent—made dress codes and curfews a thing of the past. And persistent agitation for a student-run discount bookstore—including a 1969 occupation of the LSA Building that led to more than 100 arrests—also bore fruit.

As the decade drew to a close, confrontations between youthful radicals and the elder establishment were erupting around the world. As well as becoming more numerous, demonstrations were also becoming more violent—partly out of a sense of frustration but also as a response to increasingly violent reactions by police.

“By 1968, there was a growing anger that said, ‘We need a revolution,’” remembers Richard Feldman, ’70, a leader in the U-M chapter of SDS. “There was the Tet Offensive in January, then the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the uprisings in Prague and Paris, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the student takeover at Columbia. After returning from Chicago, I became seriously committed to SDS, to forcibly changing the system from the outside.”

Feldman vividly recalls taking to the streets, marching, chanting slogans, tying up traffic, “trashing”—at that time a new term referring to the destruction of property. “Talking and peaceful demonstrations were no longer enough,” he says.

He would later opt for less-militant methods during a 40-year career with the United Auto Workers and, currently, the Boggs Center, a nonprofit community organization in Detroit. But in those last months of the 1960s, he says, “we were driven by both a passion and love for the humanity of the people and equally an anger about the brutality of American actions abroad and rising police brutality

at home. We felt we were part of a worldwide revolution.”

Despite its early leading role, Ann Arbor remained quiet compared with other campuses during the waning years of the decade. Most of the credit for this belongs to U-M President Robben Fleming, a former labor negotiator hired in 1967. Unlike the leaders of other universities, Fleming was always ready to open a dialogue with students and rarely called in police to break up a demonstration. He wisely realized that strong-arm tactics were counterproductive because they turned protestors into martyrs, with the inevitable result that the protest became larger and more disruptive.

Fleming had a polar opposite in Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey, whose favorite pastime seemed to be kicking ass and taking names. (During his reign, the county jail was popularly known as “Harvey’s Hotel.”) In 1968, when hundreds of students joined a sit-in at the County Building in Ann Arbor to support protesting welfare mothers, the sheriff called in the riot squad, complete with rooftop snipers, attack dogs, and a hovering helicopter. Nearly 250 demonstrators were arrested.

Less than a year later, Harvey again proved Fleming’s theory when the sheriff presided over a three-night fracas between lawmen and local youths that turned South University Avenue into a battlefield. In response to an unauthorized street party, Harvey and his deputies rushed in with tear gas and night sticks, inciting the kids to reply with rocks and brickbats. The sheriff’s answer was more deputies, more tear gas, and an armored car. After hundreds of injuries and 70 arrests, peace was finally restored through the intervention of an unarmed citizen’s patrol consisting of the city leaders and U-M faculty.

The 1960s were officially over at midnight on Dec. 31, 1969. But that final tick of the clock didn’t bring an end to the turmoil. In fact, the most turbulent year of the 1960s was arguably 1970. In Ann Arbor that spring, the SDS “crazies” were smashing windows in the ROTC building, the newly formed Tenants Union was embroiled in a bitter struggle with the city’s intractable landlords, and environmentalists were holding a gigantic Earth Day teach-in that attracted an incredible 50,000 people to the Michigan campus.

Plus, the Black Action Movement led a massive strike in early 1970 that involved thousands of students and faculty that nearly shut down the University. It ultimately succeeded in forcing the administration to promise a significant increase in minority enrollment.

Similar disruptions were taking place in other cities around the country, and to many it must have seemed that the revolution was indeed finally at hand. But in May, the Ohio National Guard, which was called to Kent State University to disperse students protesting the war, shot and killed four students. This tragic incident marked the beginning of the end of the mass protest movement.

The ’60s—in Ann Arbor and around the globe—were a time of enormous and rapid sociopolitical change. Admittedly, the vast majority of people never carried a sign or sat down in protest. But those who did so, out of a sincere desire for peace, freedom, and equality, left a legacy worth preserving.

About the Photos

As a freshman in 1967, Jay Cassidy responded to an open call for reporters and photographers at the Michigan Daily. His body of work at that time didn’t make up much of a portfolio; it was, in fact, a single photo he had taken of children while visiting France. But the photograph and a subsequent interview with the Daily’s photo editor were enough to get him an initial assignment.

Little did he know that over the remainder of his undergraduate years, he’d be an eyewitness to history. He covered not only events at and around the University, but went on the road to document Robert Kennedy on the presidential campaign trail, protests at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the 1969 March on Washington, and other milestones of that period.

“The Michigan Daily took an attitude that ‘we’re going to cover like a national paper,’” says Cassidy, ’70. A tiny number of those photos appear here.

Since graduation, Cassidy has enjoyed a successful career as a film editor, earning Academy Award nominations for “American Hustle,” “Silver Linings Playbook,” and “Into the Wild.” And it was in 2006 that he responded to a request from the U-M Bentley Historical Library for photos from former Michigan Daily photographers.

In 2010, he donated his entire collection, some 5,000 35 mm negatives and 4,882 digital scans, creating the Jay Cassidy Photograph Collection, 1967-70. It is part of the larger Michigan Daily Alumni Photographers Project. He speaks of the donation as a way of giving back.

“I can’t claim ownership of them,” he says. “I had the privilege of working for the Daily at Michigan.” And he’s excited to know that the public can access the photos at any time, now and into the future. “That’s why they’re there: for other generations to look at and interpret in their own way.”

Alan Glenn is president of the Michigan History Project, a nonprofit educational organization currently assembling the definitive history of Ann Arbor in the 1960s. Visit michiganhistoryproject.org/a260 for more information.