The Education of James Earl Jones

•

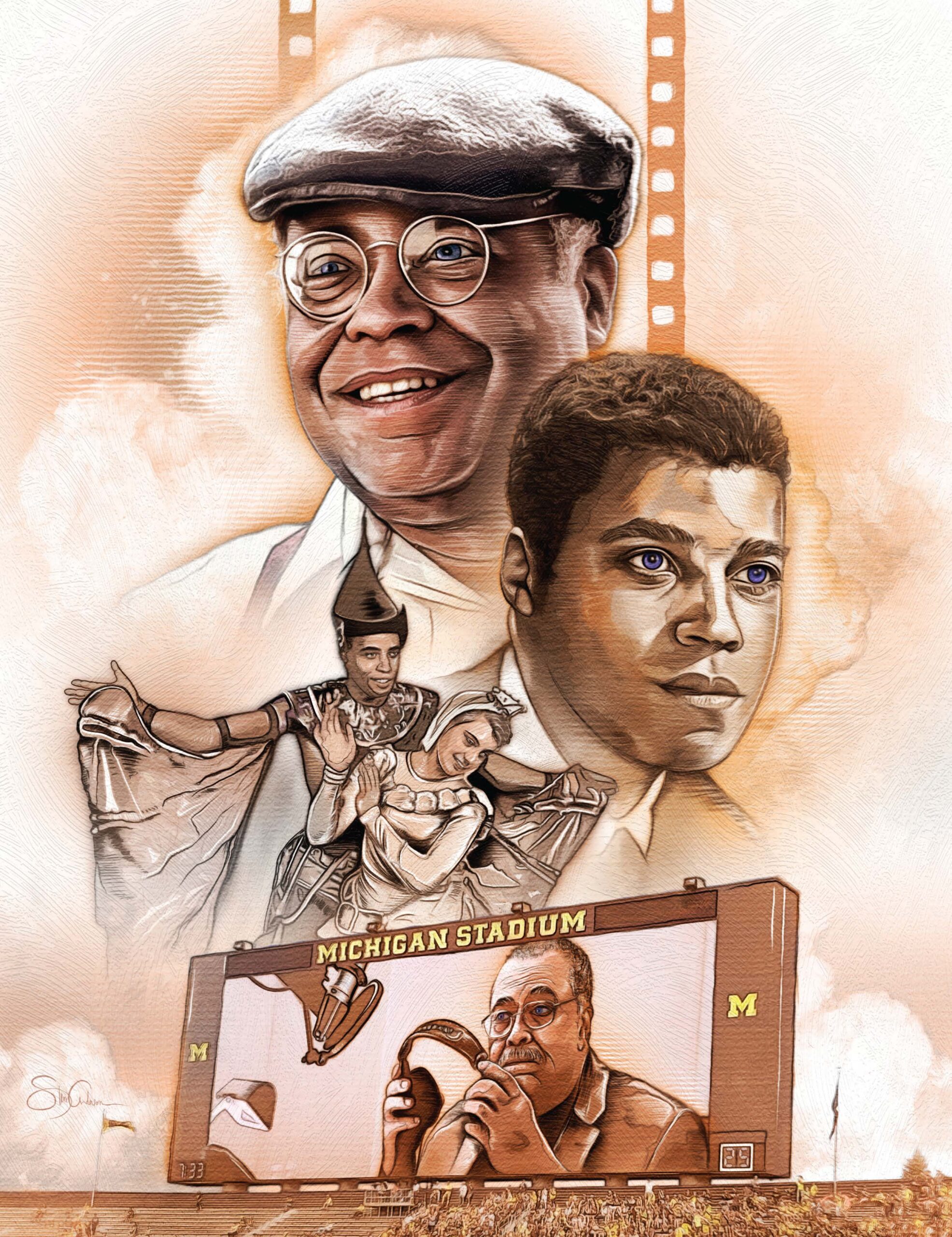

Illustrations by Steve Anderson

Long before becoming one of the most famous voices in the world, James Earl Jones, ’55, HLHD’71, spoke little for close to a decade.

At 5 years old, Jones was nearly separated from his family and left with unknown relatives in Mississippi. The resulting trauma of begging to move to Michigan with his grandparents and the fear he’d be abandoned had led Jones to develop a debilitating stutter. So, for much of his childhood, Jones kept silent, later claiming he “was practically mute.”

“One reason for being mute is the fear that if you say what you truly feel, you will be banished, abandoned, censored out of existence. I look back and see that my stuttering and muteness constituted a form of self-denial. I was robbing myself of any presence,” Jones said in a 1993 article for the Traverse City Record-Eagle.

This continued until his high school English teacher, who had been working with Jones to manage the persistent stutter, insisted Jones read his poetry assignment aloud to the class: an ode to a grapefruit.

“Professor Crouch and I had stumbled on a principle which speech therapists and psychologists understand,” Jones had said. “The written word is safe for the stutterer. The script is a sanctuary. I could read from the paper the words I had composed there, and speak as fluently as anybody in the class.”

In a 1993 interview for The Ann Arbor News, Jones explained how reciting well-written work out loud helped him overcome stuttering.

“It’s true for singers as well as speakers. It has to do with rhythms that are inherent in good poetry and good writing in general. When you pick up on those rhythms, you suddenly find it’s easy to speak.”

Jones died on Sept. 9, at the age of 93. He was a proud lifelong Wolverine who faced challenges when he arrived at the University of Michigan in 1949 as a first-generation student from a family of subsistence farmers. But it would be at U-M where he would flourish and begin his long and remarkable acting career.

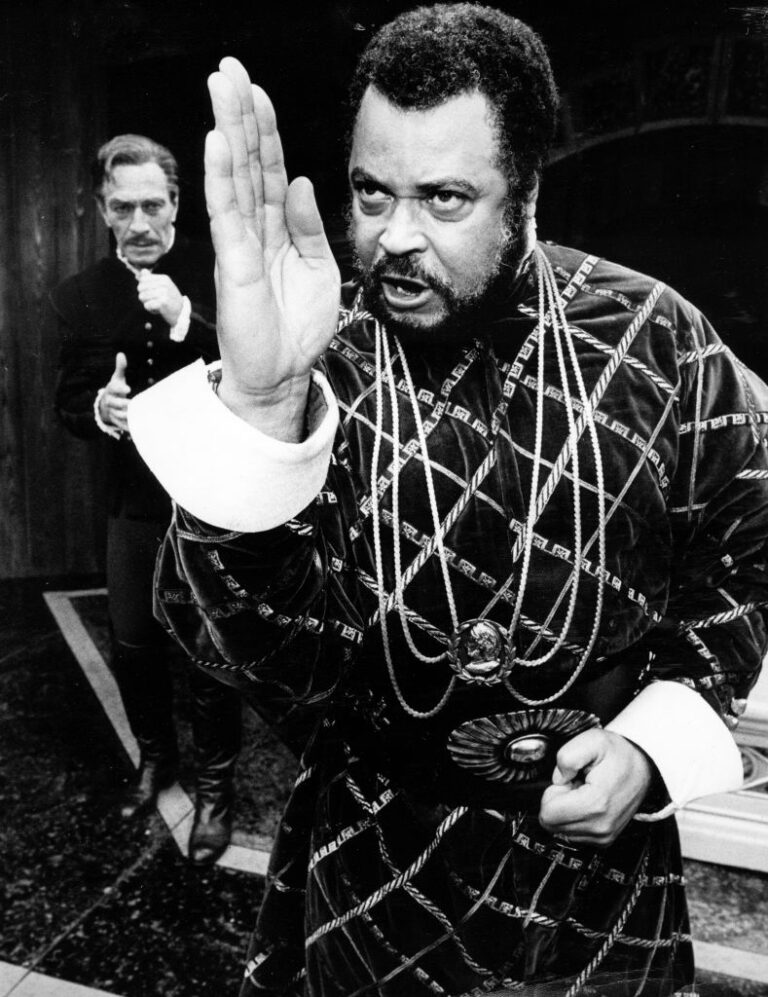

Jones would go on to embody more than 100 roles including Darth Vader in “Star Wars,” Mufasa in “The Lion King,” the mystical Terence Mann in “A Field of Dreams,” and King Jaffe Joffer in “Coming to America.” He would become an EGOT winner and be inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame while also receiving the Kennedy Center Honors and a National Medal of Arts. But not before enrolling at the University of Michigan with the hope of becoming a doctor.

Humble Beginnings

In Dublin, Michigan, Jones grew up on his grandparents’ farm, attended a one-room schoolhouse, and graduated high school in a class of 15 students.

He got his first glimpse at how different the world might be in Ann Arbor when he traveled to Traverse City, Michigan, to sit for his college entrance exam.

“I remember having cow manure on my boots … and sat there [with] a whole array of students … no others dark like me, not even Native American, and there were a lot of native Chippewa Indians in our area. But I was the only dark person there,” he recalled in an interview for The HistoryMakers, a nonprofit committed to preserving the personal stories of African Americans.

Once he arrived on campus, Jones found the vastness of university life exhilarating.

“The size of the University of Michigan was important to me; I had been a frog in a small pond. That had been my life because I was a rural person. But the size of the University of Michigan gave me a sense of the scope of humanity. A larger life than I had been aware of,” he said in a 1975 interview with Michigan Alum.

Jones was active on campus. Like many others, he attended football games. He also tried out for the track and cross-country teams and, while he believed he was competitive, he dropped athletics when he “ran into some Scandinavians at Michigan that could run like gazelles.”

Soon thereafter, Jones joined two military student groups: Pershing Rifles, a military fraternal organization; and Scabbard and Blade, a college military honor society. Both were natural extensions to his participation in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). After college, Jones would go on to serve in the Army from 1953-55.

After taking an exam in high school to receive university funding, Jones attended U-M on a Regent’s Alumni Scholarship, but the award was not enough to cover full tuition and board. To make ends meet, Jones cleaned as a janitor at the Michigan League, delivered the Sunday edition of the Detroit Free Press to students in dormitories, modeled for art classes, and answered phones at the University’s main switchboards.

With a full schedule, Jones kept to the camaraderie of his fellow cadets. He wrote in his 1993 autobiography that he and his ROTC colleagues “were loners together” and felt isolated on campus because “there was such hostility, animosity, [and] antagonism” that they encountered from other students opposing military training. Anti-soldier hostility was growing across college campuses in the early 1950s and Jones experienced this form of backlash firsthand. In one instance, the ROTC honor guard was wearing required uniforms to greet foreign dignitaries when students protested by throwing rocks at Jones and his fellow cadets.

Jones faced adversity in the classroom as well.

While working his way through pre-med requirements, the first-year Jones mistakenly took a senior-level composition class that he would later label “a horror.” In one instance, while not calling Jones by name, the English professor read aloud from one of Jones’ papers, telling the other students that, while the piece had the best content in the class, it was the worst technique the instructor had ever seen.

In another searing experience, shared in a 2004 speech at Harvard University, Jones revealed what occurred because of a spelling error in one of his writing assignments.

“Why are you trying to be something you’re not?” the professor said, confronting Jones. “You’re just a dumb son of a bitch, and you don’t belong at this university.”

More than 10 years before the Civil Rights Act would outlaw segregation, racist experiences were not unique in the U.S., nor at the University of Michigan, and Jones would go on to speak about racialized experiences throughout his life.

On one of his many return visits to Ann Arbor as an alum, Jones shared with U-M theater students that racism “cannot — must not — stop Black actors from achieving the best that they are able.” The eager students listened intently in the Frieze Building’s Arena Theatre as Jones imparted that he was fully aware of the “stunted opportunities that plague Black artists but he never [was] willing to let them overwhelm him.”

In a 1994 article with Michigan Alum, Jones shared the advice he gave to young Black actors facing racism.

“Notice it, notice that it will affect somewhat your chances of getting work. And once you notice it, ignore it. Just plow right on ahead,” he said.

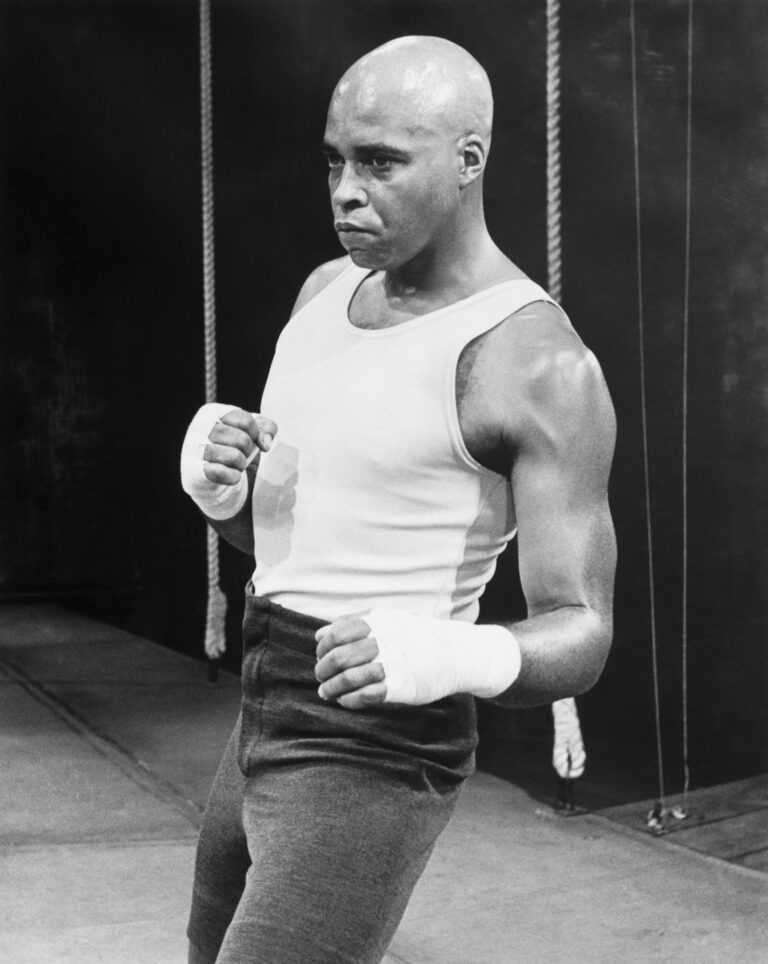

Taking the Stage

After struggling with his courses, Jones changed his major from pre-med to theater and drama in his second year at U-M. He jumped into learning all facets of stage production and first gained backstage experience such as building sets, sewing costumes, and setting up stage props and decor.

On his way back to Michigan from a ROTC encampment in 1952, Jones arrived in New York for the first time and spent several days with his father, actor Robert Earl Jones, attending operas, ballets, and theater productions. One of the concerts was particularly meaningful — a special black-tie event to hear and meet his father’s friend, the notable actor and singer Paul Robeson.

Jones recalled his experience upon hearing Robeson’s first few notes at the performance, “I felt my body vibrate, at once jolted by his energy and soothed, as if I were being rocked in a cradle.”

That evening, Robeson warmly embraced Jones upon meeting him backstage after the show. In one night, Jones bonded with his father and Robeson, who exemplified that a career in the world of theater and performance was possible.

As he began to explore his new major, Jones auditioned for small, supporting roles for productions on and off campus. He auditioned for a minor role in the theater department’s fall 1952 production, but was instead encouraged to try out for a larger, supporting role by his theater professor and mentor, Claribel Baird Halstead, MA’36, which he subsequently won.

Within a few months, in the 1953 spring semester, he played the lead character in “Deep Are the Roots.” The play tells the story of a highly decorated Black veteran who returns home to the South’s prevailing racism. The script’s realistic take on race wasn’t necessarily accepted by all audience members; Jones recalled in the 1994 Michigan Alum article that “the show went on, despite the interruption during one performance when a graduate student rose and ostentatiously exited to protest a scene between me and the white actress playing opposite me.”

As his stage roles grew, Jones’ oratory skills led to incandescent performances. Halstead, who would become a lifelong mentor and friend to Jones, noted Jones’ raw talent and the cadence of his voice.

“He was a very fine actor. He always had a remarkable voice, for which no teacher is responsible,” she said in a Michigan Today article.

Witnessing his talent, Halstead created opportunities for Jones to showcase his acting. She had intentionally chosen “Deep Are the Roots” as the spring production, intending for Jones to step into the lead role.

“I did that to give him a good role. In those days audiences didn’t accept white people in Black roles and Black people in white roles,” she explained to Michigan Alum in 1994.

“I deserve no credit except to have given him an opportunity to do it, to give him the confidence that he could do it.”

Echoes in Ann Arbor

On game day in Ann Arbor, minutes before the Michigan football team emerges from the stadium tunnel onto the vast football field, the anticipation is palpable. The bells begin to toll and more than 100,000 fans roar as the massive stadium screens show Jones donning his studio headphones, adjusting his microphone, and proclaiming “This is the University of Michigan.” Staccato, dramatic, and deeply memorable in Jones’ powerful baritone.

Hearing Jones describe not only the football tradition, but the academic standing of “the greatest university in the world” is a rite practiced by thousands of U-M students, alums, season-ticket holders, and first-time attendees at each home game.

And it’s one of many ways Jones’ legacy lives on at U-M.

For Jones, “the Michigan years were so crucial” because access to a formal education embodied what his own family had desired for him — a future that would allow him to escape his family’s poverty. At U-M, Jones learned his craft, met others in the drama world who would support him throughout his career, and gained a world-class education. It was a turning point that opened up myriad possibilities when he moved to New York City.

For the remainder of his life, Jones stayed connected to the University of Michigan. During his book tour, he visited campus and held deep conversations about his life and career while also doling out advice. In 1993, Jones co-chaired the William and Claribel Halstead Scholarship Endowment to support students in the drama department. And, more than 60 years after receiving his degree, Jones responded to then-head coach Jim Harbaugh’s, ’86, request to narrate the now iconic football video played at home games in the Big House. For Jones, the University of Michigan was a vital step in his lifelong success and he celebrated what it meant to be a U-M alum.

Lorena Chambers, MA’96, PHD’20, POSTD’23, is a postdoctoral research fellow for U-M’s Inclusive History Project and the history department.