One U-M professor is not just writing about poverty, he is addressing the problem head-on through Poverty Solutions, a new campuswide initiative.

As a student at Oberlin College, H. Luke Shaefer assisted poverty-stricken families. He called landlords and utility companies, trying to keep people in their homes with working electricity. Shaefer—who knew poverty firsthand, having grown up in a low-income household in Ann Arbor—also questioned the structural issues behind these emergencies, such as a lack of affordable housing and adequate-paying jobs.

His impassioned interest led to a master’s and doctorate in social service administration from the University of Chicago. Now an associate professor at U-M’s Ford School of Public Policy, he is serving as the director of a new multidisciplinary University initiative called Poverty Solutions.

Unveiled by U-M President Mark Schlissel in October 2016, Poverty Solutions’ mission is to inform, identify, and test innovative strategies to prevent and alleviate poverty. To that end, U-M researchers from a number of schools and colleges are teaming up with government officials, policymakers, and community members to run studies and interventions. One pilot project, for instance, pairs the Ross School of Business with the Detroit nonprofit Focus: HOPE, offering low-income residents small grants to overcome significant financial obstacles.

“We want to do very actionable things where we can see concrete results,” said Shaefer, who co-authored the award-winning book “$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America” with sociologist Kathryn J. Edin of Johns Hopkins University. In 2011, the two traveled to Chicago, Cleveland, and towns and villages in Mississippi and Tennessee, uncovering an epidemic of cashlessness that has arisen during the last two decades in the wake of welfare reform.

Michigan Alumnus recently spoke to Shaefer about Poverty Solutions and his book.

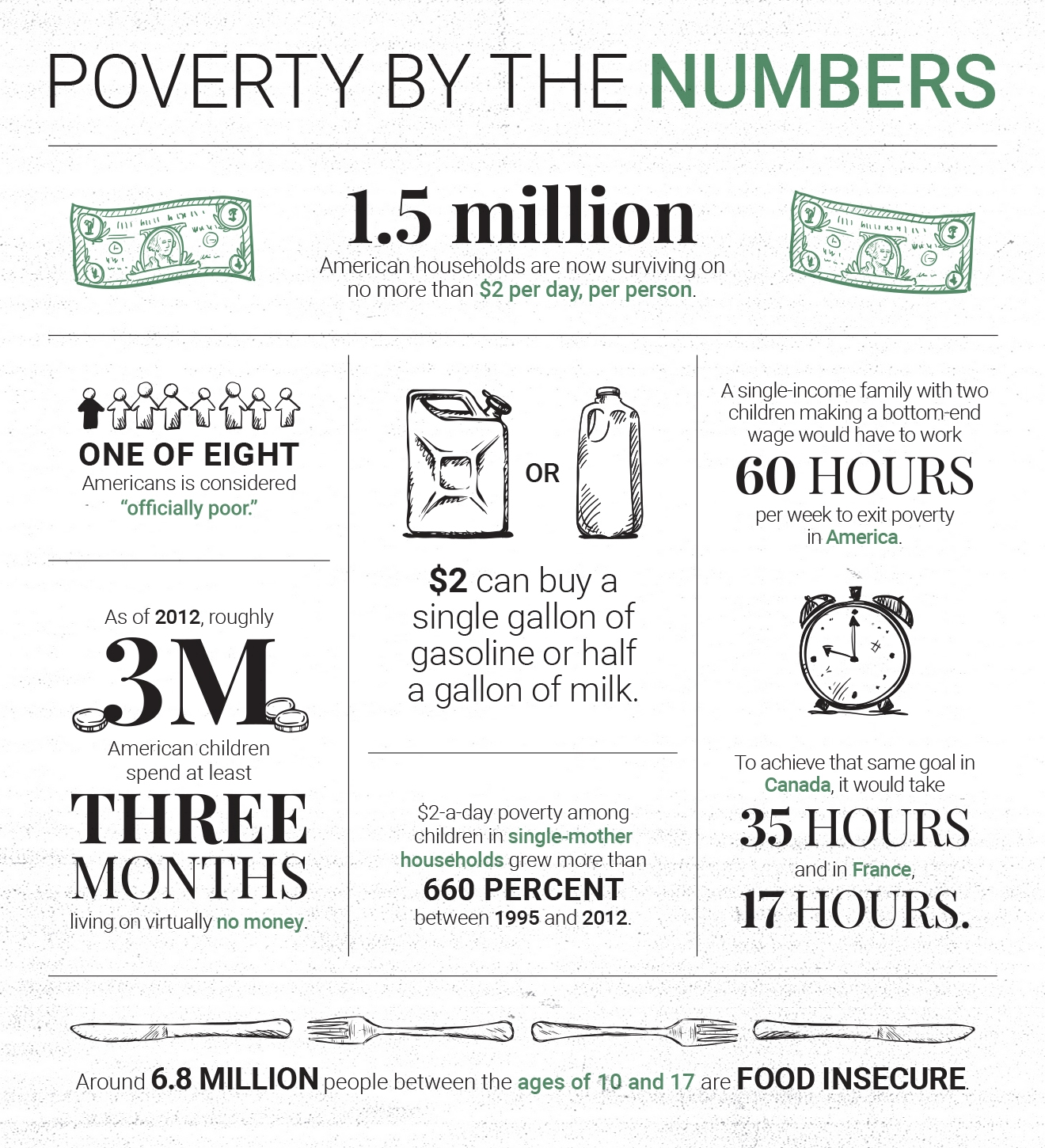

The title of your book refers to the 1.5 million American households now surviving on no more than $2 per day, per person. That’s double the amount of households in the same circumstance 15 years ago. But if people have access to food stamps and housing, how much do they really need cash?

To Kathryn and me, the best evidence that cash really matters is the great lengths families will go to for that little bit of cash, whether it is selling their plasma or trading sex. We argue that people’s lives are consumed with the process of generating a little cash to make it to the next day and, as a result, they’re more and more socially disconnected. This is important to us, because some people interpret our book as saying we should go back to the old welfare system.

Why shouldn’t we go back to the old system? The welfare program up to 1996 involved long-term cash assistance and didn’t require recipients to have a job. It served 14.2 million people, two-thirds of them children. Its replacement, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), sets a time limit on cash benefits and ties benefits to employment. That program serves only 4.4 million people today.

The old welfare program wasn’t well thought out—it was hugely stigmatized and it wasn’t well-liked by families who received it. But in the average state now, only about one out of every four TANF dollars goes to cash assistance, as there is very little regulation, almost none, dictating how the states use the money. It can pretty much be used for anything that justifies helping needy families achieve self-sufficiency. So it puts cash-strapped states in a really hard position not to pilfer the money on other types of programs, like education. In Michigan a few years ago, we had a big budget crunch, especially around college financial aid, and so the state shifted $100 million of TANF funds for the cash assistance program into the state college financial aid budget. So every year, we now have just under $100 million going to financial aid for people attending college, and most of that goes to families who are relatively high income.

So what do poor people themselves say would help?

We ask families, “If we came back in a year and you were doing really well, what it would look like?” They say, “I’d be working in a decent job, getting paid $10-12 an hour.” We want to do a lot more to help people find and stay in jobs if that’s what they want. Many of our families spoke eloquently about how work was a way that they could have a structure in their day and contribute. We don’t give a lot of opportunities to poor Americans to do something meaningful. If there are good jobs, and some support to maintain those jobs, it’s socially incorporating and it’s what people want, far more than being unemployed and taking a welfare check. I think that’s the type of program that Americans would support.

Your research career has mostly been about crunching large-scale data. How did you like doing fieldwork?

The two forms of inquiry really enhance each other. For example, I would often notice a divot on the inside of the arms of the people we met. Originally, I assumed it was a drug track line, but they were scars from selling blood plasma. We see people selling their blood plasma to survive. They have no other money. Plasma sales went from about 12 million units sold in 2006 to 38 million in 2016. There’s no other country with a market in the world that lets you sell your plasma twice in one week. The United States accounts for about 65 percent of the world’s plasma supply. We’ve been called the OPEC of blood plasma. Before doing fieldwork, I knew nothing about the world of “big plasma.”

Your book suggests we need policies enabling job creation, higher wages, better hours, housing, and a cash cushion. Do you think these things will come to pass?

I’m worried about what’s going to happen in Washington. But I have hope that in the long term, there’s potential to see positive changes at the federal level. And a lot of people are thinking deeply about these things at lower levels. State and city policymakers are being proactive. There’s a very well-liked program in Albuquerque where the city approaches folks who are panhandling and offers them a job for the day. Here at U-M, we are partnering with the State of Michigan on a program called Community Ventures. It works with employers to create full-time positions that pay $10-12 an hour and then provides a coach to help workers stay in the program. We’re also in discussions with the City of Detroit about ways we can support their efforts to tackle intergenerational poverty in the city.

Does Poverty Solutions have an educational aspect on campus?

Yes. We want to increase the educational content on poverty and make sure some students come through U-M with knowledge on poverty. We had an engagement event where we had about 125 folks, many of them students, come to hear the director of housing for the City of Detroit speak. Then they engaged in action-based, small-group projects in Washtenaw County, Detroit, and a rural part of the state. We’re going to try to do more of those.

A lot of U-M students know about poverty firsthand, as you did as a college student. What is U-M doing to support them?

The Maize and Blue Cupboard is a student-run food distribution pantry. Once a month, they have over 200 students come in and get a bag of groceries. People are more familiar with the statistics of how affluent U-M students are, but it is important to recognize that is not the case for all of our students.

Source: twodollarsaday.com. For more information, visit poverty.umich.edu and twodollarsaday.com.

Jenny Blair is a freelance reporter and writer whose work has appeared in a number of publications, including Discover, New Scientist, and The Washington Spectator.