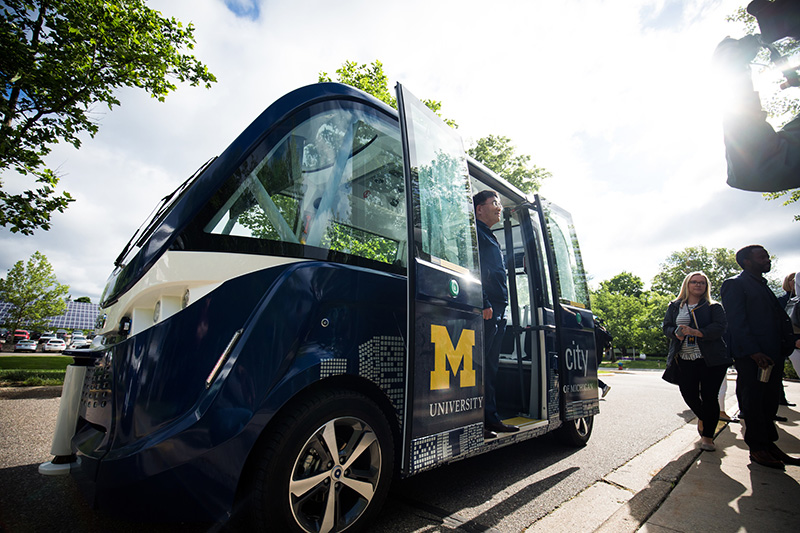

It looks like a cartoon car, nearly as wide as it is long, with round bumpers and oversized windows. Gliding silently along, it moves through the streets of the North Campus Research Complex, stopping to pick up and drop off passengers on a 1-mile route. Yet unlike other campus transportation, this little blue bus has no driver behind a steering wheel.

Instead, on this early June day during its second week in operation, I am welcomed by conductor Eileen Hoekstra, ’92, MSE’98, who is standing next to one of the 11 passenger seats. I happily buckle up, feeling the comfort of the gray upholstery padding a plastic seat, and am ready for my first driverless ride.

Once en route, I admittedly feel a bit jarred at the lack of a steering wheel and driver.

My fellow traveler is Greg McGuire, the lab director of Mcity, the University’s center for the study of future mobility. His lab is responsible for this latest project: researching how passengers react to a driverless shuttle as a way to gauge consumer acceptance of the technology.

“We’re not providing it as a service,” says McGuire of the two shuttles currently operating Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. “It’s a research project masquerading as a service.”

Once en route, I admittedly feel a bit jarred at the lack of a steering wheel and driver. Fortunately, I know Hoekstra can control the vehicle, if needed. Along with an emergency stop button, she can manually drive the shuttle with an Xbox 360 controller and punch buttons into a box on the wall if she needs to reset the route.

Meanwhile, all passenger movement (including my own) is being meticulously tracked, via overhead cameras and microphones. Exterior cameras are also recording the shuttle’s performance as well as reactions of passersby and motorists. Researchers will analyze this data to measure user trust and develop better designs for safety and efficiency. Mcity says riders’ privacy is safeguarded through a data protection plan.

Built by the French firm NAVYA, the shuttle runs entirely on electricity and is guided by GPS, which pinpoints locations, and invisible laser beams that navigate the surrounding area. U-M paid $500,000 for the shuttles and the systems that operate them.

During my journey, Hoekstra gets up and down from her seat several times, manually adjusting the route to avoid other vehicles. She says it is those outside the shuttle, not inside, that test the baby bus’s limits the most.

“People step out in front of it,” says Hoekstra, who conducted GPS research at the University in the 1980s. (In fact, during my trip a man wearing headphones and looking down at his mobile phone crosses the road without a glance at the tiny, noiseless shuttle.)

Other people, she explains, stand in the middle of the road simply to see how it will react. And then there are the tailgating motorists. This is not an unexpected issue, as its runs at a tortoise-like pace of 12 mph.

McGuire says the shuttle should operate even in the worst of Michigan’s weather, from intense rain to heavy snowstorms. But in case an umbrella-wielding student or snow-blowing machine suddenly obstructs its path, he reassuringly adds, “We want our conductors to maintain good visuals.”

The biggest disruption since the shuttle started, however, has been parked vehicles on its route. It starts in front of Building 10 at the complex, winds its way around North Campus, and eventually stops at the commuter parking lot at Hubbard and Hayward streets.

What does the shuttle do if it detects an obstacle? In the case of people, it stops until the person moves away. In the case of a parked car, the shuttle stops and honks to get the motorist’s attention. If the obstacle does not move, the conductor takes over the controls and detours around the vehicle.

A true researcher, Mcity’s McGuire does not see these interruptions as annoying so much as enlightening. “We want to study how other people use the roads around the shuttle. Are they more aggressive? More bold? More confrontational?” he asks.

The project itself ran into delays when the original fall 2017 launch date turned into spring 2018. Summer campus construction has also resulted in a shortened route. Once that work is complete, the free ride will make a 2-mile loop running deeper into North Campus, extending to the Lurie Engineering Center. Though available to all members of the U-M community, riders may be asked to show University identification.

In the meantime, a new summer pastime might be watching how many passengers and motorists do a double take when they see a small bus with no driver.

Micheline Maynard, a Knight-Wallace fellow at U-M in 1999-2000, is a regular contributor to Michigan Alumnus.