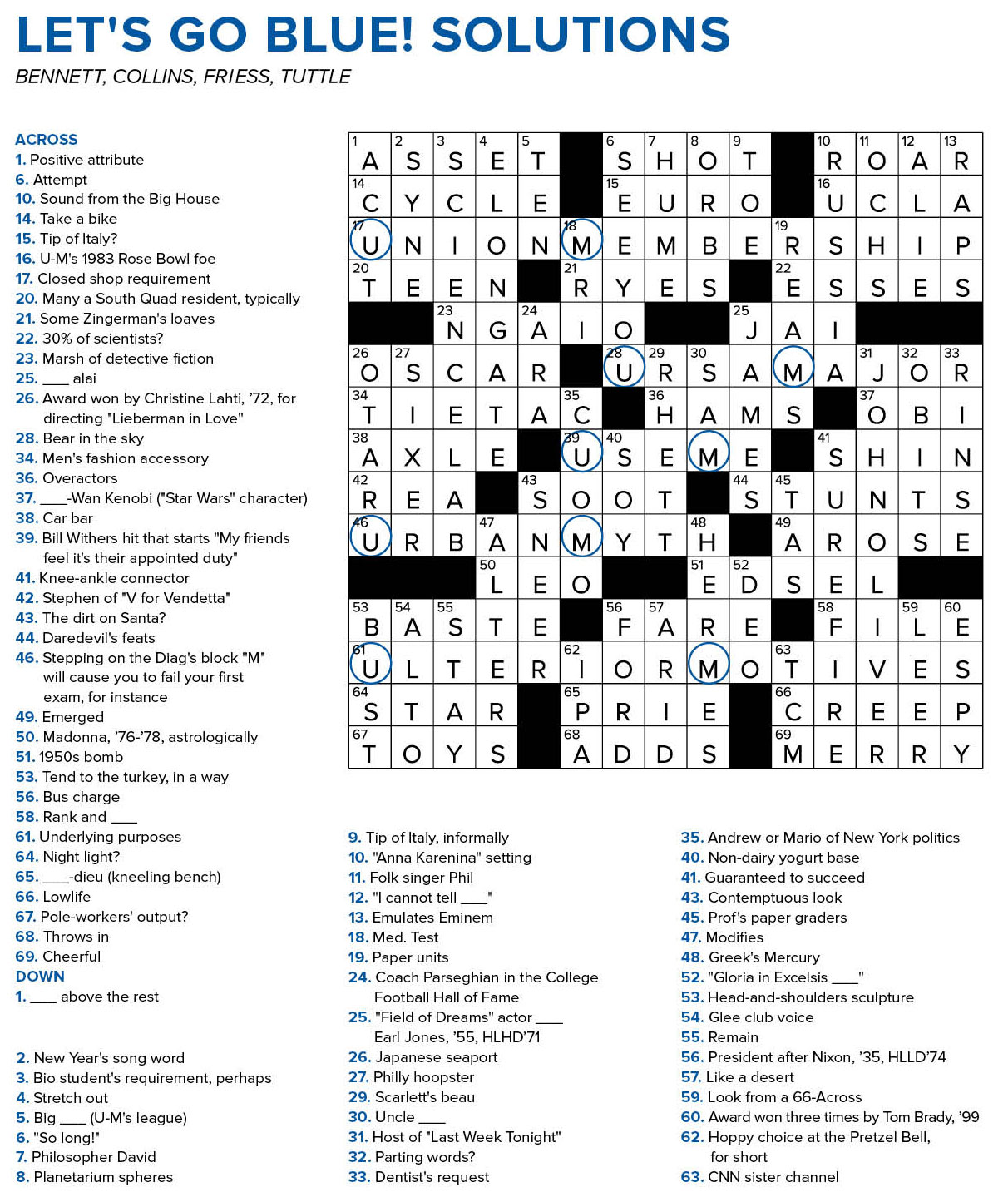

IN THE HOURS BEFORE THREE of the nation’s top crossword constructors came to my home in Ann Arbor to build the puzzle that accompanies this article, I was sure I had our theme answers ready to roll—HARBAUGH, BIGHOUSE, MICHIGAN, and TOMBRADY. All are eight letters! What more did we need?

Then, as Peter A. Collins, ’80, Tracy Bennett, ’89, and James Tuttle, ’02, gathered around my dining table and started kicking around other, better ideas, I felt embarrassed to offer up my words. To delve deeper into that part of our crossword-constructing brainstorm session would ruin the discovery for puzzle solvers. That, as Bennett explains, would be known as a “category theme” puzzle, a lesser form that people hire folks like Collins, Bennett, and Tuttle to create for weddings and the like.

To try your hand at solving the crossword created for this article, click here or scroll to the end.

“If you send something like that to Will Shortz, it’ll almost always get rejected unless it happens to be the anniversary of something because it requires no wordplay,” says Bennett, referring to the New York Times crossword editor.

Rookie mistake—and an enlightening one. Like so many who habitually take ink (never pencil!) to the grid, I’d given little thought to the craft behind the pastime or ever imagined that the woman in the booth near me at the coffee shop might have written the puzzle I was solving. Yet in Ann Arbor, that prospect is impressively likely. Two consecutive Sundays in April 2019, the blurb accompanying The New York Times Magazine puzzle indicated the constructor was a U-M graduate, reminding many that successful cruciverbalism (the construction of crossword puzzles) grows wild in Tree Town.

“Puzzle interest definitely gets concentrated in a few parts of the world,” says Ben Tausig, ’02, a Stony Brook University music professor with nine published New York Times puzzles under his belt. Some college towns—Ann Arbor; Austin, Texas; and Providence, Rhode Island, among them—breed a constructing culture, he says.

Adds Andy Kravis, ’09, The New York Times crossword assistant editor, “It’s wherever there are people who are serious about puzzles in great concentrations and have the time to devote to the activity and the wherewithal to learn more.” (Kravis, who joined the paper in March 2019, is a test solver for the paper, checking puzzles for accuracy, fairness of clues, and difficulty level.)

A café encounter almost a decade ago in Ann Arbor is how Tuttle—who teaches mathematics at Washtenaw Technical Middle College and has written seven New York Times puzzles—met Collins. Collins spotted him solving a New York Times puzzle and asked how it was going. He then revealed he was its constructor. “Sure you are, pal,” Tuttle retorted.

But it was true. Collins, the mathematics department chair at Huron High School in Ann Arbor, is one of the New York Times’ most prolific crossword builders, with 110, including one of those two Sunday puzzles in April 2019. He popped into Tuttle’s life at just the right time. Tuttle had been trying to teach himself how to write crosswords by generating ideas and attempting, but failing, to create grids using graph paper.

“I just didn’t know how to get from here to there,” Tuttle says. “Pete was willing to meet with me at a different coffee shop a few weeks later. He showed me the crossword software and websites he uses and got me moving in the right direction.”

“Like so many who habitually take ink (never pencil!) to the grid, I’d given little thought to the craft behind the pastime or ever imagined that the woman in the booth near me at the coffee shop might have written the puzzle I was solving. Yet in Ann Arbor, that prospect is impressively likely.”

Such mentorship and camaraderie go a long way. Will Nediger, MA’14, PhD’17, taught Kravis after they met while competing at College Quiz Bowl, a campus intramural tournament. “I would not have been nearly as successful without a mentor like Will,” says Kravis, who co-authored his first published puzzle (for the Los Angeles Times) with Nediger. “I had made a couple of puzzles alone, but there were understandings about crosswords I didn’t have.”

Or as Tuttle explains the art of cruciverbalism, “It’s less looking at the words as things with meaning and more looking at the words as strings of information. Like in Scrabble, they’re not words, they’re playable strings.”

While being published in The New York Times is important to a constructor’s credibility—because the Gray Lady’s daily grids are synonymous with the hobby—several U-M alumni constructors are taking the craft in new, diverse directions.

Last year, Bennett, who has published four New York Times puzzles, co-founded Inkubator, which emails biweekly puzzles written by women to subscribers. She also writes puzzles for BUST magazine; the Crosswords With Friends app; and Groundcover News, the nonprofit monthly that benefits Ann Arbor’s homeless population.

Kravis, who is gay, contributes to Queer Qrosswords, an annual set of themed puzzles sent in exchange for recipients’ donations to LGBTQ causes. In 2015, he also co-founded the annual Indie 500 crossword tournament in Washington, D.C.

Tausig is a groundbreaker, too, as editor of the American Values Club crossword, an oft-irreverent weekly puzzle with some 6,000 paid subscribers.

On our second gathering to complete our puzzle, I am savvier. By then, we have our theme and their answers, and Collins has used his software to fill in the grid. That may sound easy and automated, but it’s really a starting point because a lot of the answers provided by software are too obscure, awkward, or outdated to include. That is a key difference between good and bad puzzles. The best-themed ones offer smart wordplay in clueing while minimizing “crosswordese—terms or names that appear in puzzles only out of necessity to hold the rest of the grid together.

As we work through the puzzle for organic places to include Michigan-related clues, I have a big moment. The answer is MITT, and I suggest the clue “Romney, who once said Michigan’s trees were ‘the right height.’” Bennett and Collins (Tuttle isn’t there) think this is fun and clever. I feel like a pro.

Then we realize one of the words crossing with MITT is CAMOMILE, as in the tea, but it is not spelled the normal way (CHAMOMILE). Bennett and Collins could keep it and indicate in the clue that the answer is a spelling “variation,” but that is an ugly cheat that constructors avoid unless desperate. Instead, they cut the word and unravel that entire corner of our grid. My clue is sacrificed on the altar of our readers’ solving pleasure.

“That’s how it goes sometimes,” Collins consoles. “It’s not as easy as it looks, is it?”

Steve Friess is a Michigan-based freelance journalist and a 2011-12 Knight-Wallace Fellow at U-M.

Editor’s note: This article originally wrote that Peter A. Collins was a 2008 graduate. He earned his U-M degree in 1980.