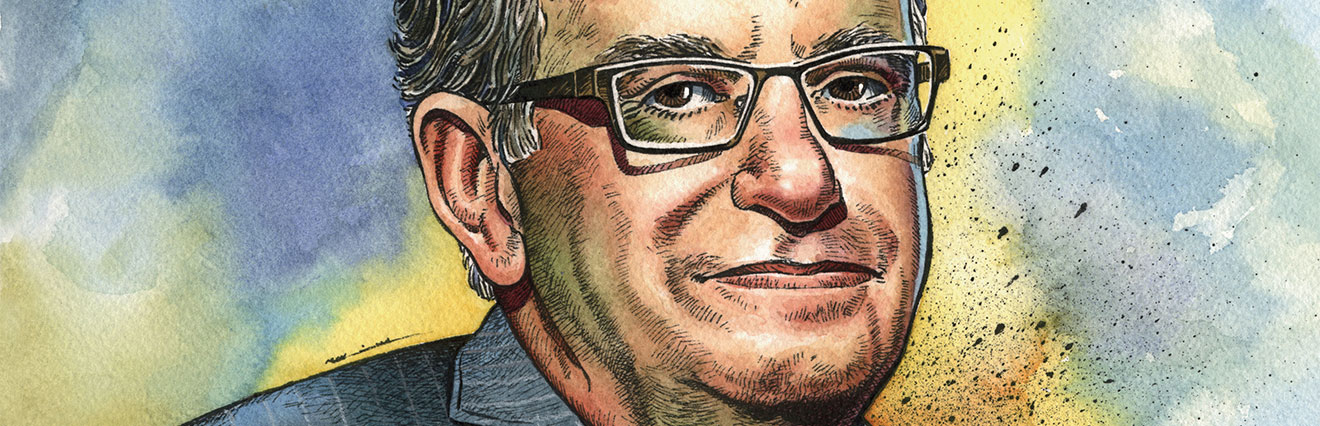

It’s been called the most unpredictable presidential election the country has ever seen, and there’s an argument to be made that nobody is keeping a closer eye on all the developments than Norman Ornstein, MA’68, PhD’72.

You can tell the moment you walk into the office of one of the nation’s pre-eminent political scholars at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C. He clearly devours information. Mounds of books and folded newspapers cover every surface, file drawers bulge open, and a television displays the latest from the campaign trail, which on this day is waiting for the latest speech from Hillary Clinton.

Ornstein has been carefully watching politics for decades, as evidenced by framed photos around his office showing him and his family with the likes of George and Laura Bush.

Ornstein himself is friendly, outgoing, and witty, though focused on the day’s political events. He flashes a smile as he glances at the television. “I was hoping to catch her speech before we talk,” he says. He mutes the television but continues to glance at it. Clearly, there is not a moment in the political cycle that the 67-year-old political analyst misses.

Ornstein has had his finger on the pulse of Washington for 40 years. A resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, he is also contributing editor and columnist for National Journal and The Atlantic. And he has authored three books, including 2012’s “It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of Extremism,” written with Thomas E. Mann, MA’68, PhD’77.

Ornstein, who considers himself a centrist, has been dubbed the “king of quotes” for his talent in offering pithy, educated sound bites. So he frequently is seen on news programs and read in newspapers offering analysis of the day’s political events. He doesn’t just comment on politics, though. He helps shape policy, too, most famously leading scholars in a working group that helped draft parts of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. Known as the McCain-Feingold Act, it helped reform the campaign finance system.

“Norm is a polymath. He knows more about more things than anyone I know,” says Mann, a resident scholar at the more left-leaning Brookings Institution. “His preferred audiences for his writing and speaking are large, diverse, and nonacademic.”

One longtime member of that audience is Sen. Al Franken, D-Minn. “I think he is incredibly smart. He reads everything. He also has incredible gifts for being able to explain things so people can understand them,” says Franken, who grew up in the same Minnesota suburb as Ornstein, although they didn’t meet until years later.

“I guess Norm and I are maybe an odd couple in a certain way. But we have a common background, and when we met, I was a fan of his work and he was a fan of mine.” Their friendship is so deep that Ornstein was ordained online as a minister so he could preside over the wedding of Franken’s daughter when the family’s chosen rabbi was unavailable. Franken and Ornstein have done a few comedy gigs together through the years, too—often joking that “Norm” and “Al” add up to “normal.”

When Franken anchored Comedy Central’s “Indecision ’92” presidential coverage, Ornstein was hired as the channel’s first “official” pollster. Franken says he was so funny, viewers thought he must be a comedian. One fan letter read, “‘The guy you had playing Norm Ornstein was perfect,’” Franken recalls with a laugh.

Ornstein admits he finds less to laugh about in Washington in the midst of this unconventional presidential election and unprecedented gridlock on Capitol Hill.

“People say to me, ‘Isn’t this fun? You must be having a ball.’ And I look at them like they are crazy. I grew up in awe of our system and its institutions. I loved Congress for all its messiness, and now you have to be dismayed.”

Campaign 2016 has surprised many, but Ornstein saw the writing on the wall. He and Mann wrote about the rise of extremism and radicalization within the GOP in their 2012 book. While he says they approached the subject with academic objectivity and a goal of improving Washington’s institutions and governing process, it wasn’t received that way. The headline on a Washington Post op-ed they wrote read, “Let’s just say it: The Republicans are the problem.”

“A lot of people including Republicans in Congress saw it as a partisan assault on them,” he explains.

He expanded on the subject in August 2015 with a story in The Atlantic suggesting that anger at the establishment and status quo within the GOP would give rise to outsider presidential candidates like Donald Trump and Ted Cruz.

“I saw that Trump was a much better candidate than the press corps or political scientists were giving him credit for. He knows how to market himself and he knows the weak spots in the Republican electorate,” Ornstein explains.

His predictions have come true, and an April 2016 revision of his book updates the title to read “It’s Even Worse Than It Looks Was.” He continues to write extensively on this presidential campaign and the dissatisfied electorate he sees on both sides of the political aisle.

“Populism is alive and well on the left and right. The unhappiness with the establishment is there on both sides,” Ornstein says. “We do know we will head to the fall with two candidates who will have higher negatives than positives, and it will be a highly negative campaign.”

This is a political world that still fascinates him, even though it is vastly different than the one he entered as a young man.

Ornstein was born in 1948 in Grand Rapids, Minn. A gifted child, he graduated from high school at 14 and the University of Minnesota at 18. At Michigan, he earned his masters at 19 and his doctorate at 23.

He grew up wanting to be a scientist but developed an interest in politics at an early age, prompted in part by a grandfather who was a labor leader and an uncle in the Minnesota Legislature. He became more entranced with politics thanks to professors at Minnesota and Michigan and fully caught the political bug once he moved to Washington, D.C., as a congressional scholar and then professor.

“I became more immersed in Congress, and I didn’t see politics in starkly partisan terms. I saw some nuances,” he recalls. So he opted not to choose sides. “I decided the role I was going to play was one of an independent observer who would try, as I wrote and commented, to have people not sure where I was coming from. I did very well at that, although the last five years have been a different experience,” he says with a grimace, referencing reaction to his most recent book.

In the mid-1970s, as a professor at Catholic University, he was already becoming an expert on Congress and frequently published in academic journals. It was an arduous process involving a typewriter, carbon copies, and the mail, so it typically took two and a half years to get something into print.

Then one day, while waiting for his clothes to dry at a laundromat, he finished reading a book about former Democratic congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who represented Harlem. Ornstein decided, on the spur of the moment, to review it. He grabbed a yellow pad and pen, wrote down his thoughts, and sent it to The Washington Post. Within just a few days, the newspaper accepted the review and published it on the front page of the style section.

“Instead of being read by 700 political scientists, it was read by tens of thousands of people. I got quick feedback and I got paid. What’s not to like?” he says with a laugh.

He embraced this new medium and, along with his academic work, his reputation as a public intellectual was solidified. In that role, he calls it like he sees it—and he admits he is nostalgic for the past.

“Partisanship used to be there,” Ornstein says. “But you had leaders who would come together to solve real challenges, and you had a media that kept people honest.”

These days, he is concerned for the future. “I think there is a resiliency in the system,” he says. “Having said that, I am more worried than I have ever been. I think the nature of modern media and social media makes it harder because more and more people believe things that aren’t true.”

He is also working on a more personal issue—lobbying Congress to pass a bill that would help fund assisted outpatient treatment for individuals with a long history of mental illness. In January 2015, Ornstein’s eldest son died a decade after suffering a psychotic breakdown.

Encouraged to wrap up the interview on a more positive note, Ornstein smiles, throws up both arms, and exclaims: “Jim Harbaugh! At least we’ve got him to look forward to.”

Jennifer Davis, ’95, is a freelance writer and reporter based in Washington, D.C.