Escalating costs have made college an unattainable dream for many low- and middle-income students. But a new U-M program is taking some students one step closer to realizing that dream.

As Mark Bernstein,’93, JD’96, MBA’96, campaigned for U-M regent in 2012, he got a vivid reminder of the financial difficulties many families face in sending their students to the University. He toured the state in a bus with a sign reading “Keep College Affordable.” At his first campaign event in Fruitport, Bernstein recalls, a man approached him during a parade and said, “Hey, we can’t keep college affordable because it’s not affordable now.”

The candidate had the bus repainted to read “Make College Affordable,” and the topic has been a priority for him since he assumed the position of regent.

“We know that a Michigan degree changes the trajectory of our students’ lives, their families’ lives, and the state and our society,” Bernstein says. “You want the power of that degree to be available to every student, regardless of financial circumstance.”

In June, on the heels of a campuswide effort to promote diversity, the U-M board of regents approved the Go Blue Guarantee scholarship program to help attract students from different backgrounds, not just those from well-to-do families. Starting with the winter 2018 semester, the program offers four years of free tuition to in-state students on the Ann Arbor campus whose families earn $65,000 or less and have less than $50,000 in assets. (See details in the sidebar.)

University officials say the program puts free tuition within reach of at least half the families in Michigan.

Anushka Sarkar, U-M’s Central Student Government president, contends that “a lot of students aren’t able to come to Michigan because of the sticker shock.” She says the Go Blue Guarantee is “an excellent program because it is a first step. A lot of work will have to come after this.”

According to the Equality of Opportunity Project, the average household income for U-M students is $154,000—more than double the state’s $63,893 median family income, as reported by the U.S. Census Bureau. Some 66 percent of students come from the top 20 percent income levels, the project found. And while college traditionally is seen as a key step toward upward mobility, only 1.5 percent of U-M students come from poor families and subsequently rise to become rich adults. That income-level statistic has remained basically the same since 1980.

University officials, experts, and students themselves say the perception of Michigan as a home for well-to-do students discourages others students from applying.

“We know that a Michigan degree changes the trajectory of our students’ lives, their families’ lives, and the state and our society.”

Kedra Ishop discussed the idea of a low-income tuition program with U-M officials when she interviewed for the position of vice provost for enrollment management. She began the job in 2014, one month after U-M President Mark Schlissel took charge. He was fresh off a vacation in the state, where he discerned a “pervasive perception that the University of Michigan is unaffordable,” says Ishop.

That perception should come as no surprise. The growth of the Ann Arbor area has sent home prices soaring, and a study by Ann Arbor SPARK, a local economic development group, rated Washtenaw County as the least affordable area in Michigan.

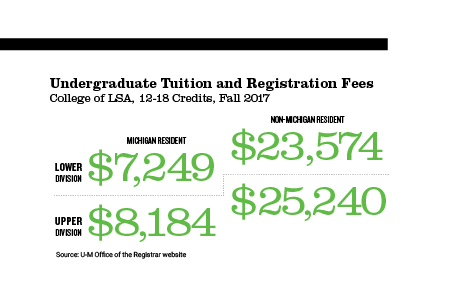

Michigan’s campus is now ringed with luxury high-rise student apartment buildings, many aimed at out-of-state and international students who make up nearly half of the overall student body. Their undergraduate tuition is roughly triple the amount that in-state students pay. (See the sidebar.)

“Our reality is that a student coming from a low-income background will arrive at this place and look around, and this will feel very expensive to them. It just will,” says Ishop, an architect of the Go Blue Guarantee. “It’s a hard nut to crack, in terms of addressing that perception.”

Josie Luttman, of Bad Axe, Michigan, found her living expenses were much greater than she anticipated when she arrived in Ann Arbor in 2016 for her first year of classes. Although she had a job in a campus dining hall, she skipped buying a textbook for one class because she couldn’t afford it and applied to terminate her housing contract after the fall semester, thinking it would be cheaper to live elsewhere. A second job at Taco Bell, plus housing money provided by her mother, who also works at Taco Bell back home, helped her bridge the financial gap.

Luttman says she met only one other student from a similar economic background, while all around her were students who talked of exotic-sounding vacations. “I can’t relate to going to India in the summer,” she says. “I go up to Mackinac.”

She was excited to hear about the Go Blue Guarantee because it could mean that more people like her are on campus. “It will make it more comfortable for those of us who are low-income students,” Luttman says. She isn’t sorry that she came to Ann Arbor, even though her financial circumstances keep her from enjoying off-campus activities, like going out for a sit-down meal or even buying a latte.

“I don’t think I’m going to be able to be the student who gets to go on a study abroad,” she says. “But I will get the degree at the end of four years.”

Go Blue Guarantee Highlights

Starts: Winter 2018 semester

Eligibility: Students on the Ann Arbor campus who are Michigan residents or eligible for in-state tuition and whose families have incomes of $65,000 or less and assets of less than $50,000

Aid: Students receive free tuition and mandatory fees for up to four years or eight semesters. Engineering students are eligible for 4 1/2 years or nine semesters of tuition. The program applies to the student’s first bachelor’s degree. The value is estimated at $60,000.

Current Students: Those who meet the eligibility requirements and are already enrolled will automatically have their tuition funded for the remainder of their college time, up to four years or 4 1/2 years, depending on their program.

Other Costs: The program does not cover room and board or books. However, students may be eligible for additional financial aid programs, including work-study.

New Students: They must apply and be accepted to Michigan and also must complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and CSS Financial Profile.

For more information, see goblueguarantee.umich.edu.

Michigan is not alone in battling affordability challenges. The Go Blue Guarantee is among 59 programs across the country that offer no-loan tuition programs for students from low-income backgrounds, says Mark Kantrowitz, publisher and a vice president of Cappex, a website that specializes in information about college financial aid and scholarships. An additional 15 programs provide no-loan tuition for all students, regardless of income, he said.

Many elite private and public universities have similar programs for students from low-income families, and some set the income threshold much higher. In April, New York state announced a free tuition program for students from families earning $100,000 or less (rising to $125,000 by 2019) who enrolled in State University of New York colleges or at the City University of New York. Instead of 23,000 anticipated applications, 75,000 students applied.

“‘Free’ is a very powerful word for marketing and recruiting,” Kantrowitz says. “Low-income students fear debt. The prospect of borrowing more money than your parents earn in a year has a chilling effect on applications.” He adds that Michigan should see an immediate bump, as high as 10 percent, in applications from low-income students in the Go Blue Guarantee program’s first year.

The program is a next step from a two-year pilot scholarship program called the HAIL Scholars, which stands for High Achieving Involved Leader. It provides four years of free tuition to its low-income recipients, who began attending Michigan in the 2016-17 academic year. In its first year, 262 students—including Luttman—from 52 Michigan counties enrolled at U-M. They were chosen based on their previous academic success and financial need, although the program did not specify a family income level.

However, as Ishop acknowledges, the HAIL program “put a label” on the students as coming from low-income families. She vows that more will be done to ensure Go Blue Guarantee recipients don’t feel isolated.

Sophomore and HAIL scholar Daija White of Redford, Michigan, agrees the Go Blue Guarantee is off to a better start. “It’s much more open, there’s more information about it, the requirements are much more clear,” says White, who plans to major in statistics with a minor in French. “Just in structure alone, you’re going to have a bigger group of people. It will (lead to) creation of a community.”

But how big should that community be, and how long should the program last? Ishop said the University is not limiting the number of students who could benefit from the Go Blue Guarantee and that the program is “purposely designed to persist and be sustainable over time.”

The Go Blue Guarantee is funded from the main $200 million kitty that Michigan has for scholarship and financial aid awards, so the school has more leeway than if it were a donor-funded, time-limited program.

“We’ve seen other models go out, and they’re too successful, and we have to pull back,” Ishop says. Michigan did not build in any kind of requirements, such as the need to maintain a specific grade point average, she adds. Students have to stay eligible to attend classes at Michigan, but that’s the only academic requirement.

While the University is not specific about how it will measure the success of the Go Blue Guarantee, Ishop’s hope is to see greater numbers of students with family incomes of $65,000 or less. She is also looking at the number of students who qualify for federal Pell Grants. These financial aid instruments are available for students whose family income is $40,000 or less, although most go to students with family incomes of $20,000 or less.

Ishop says Michigan’s Pell Grant level in 2017 was about 17 percent, but she would like to see that rise to 18 to 20 percent within a few years.

A National Perspective

Each year, the UCLA Higher Education Research Institute surveys incoming freshmen about politics, mental health concerns, and similar hot topics. In its publication “The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2016,” the institute tallied responses from 137,456 full-time, first-year students at 184 U.S. colleges and universities. The following is a peek at some of the responses regarding affordability:

Nearly

56%

had concerns about paying for college.

The severity of students’ concerns varied widely by their gender and ethnicity: 65.7 percent of women said they were either somewhat or very worried about it, compared with just 34.3 percent of men. Twenty-two percent of black students, 24.7 percent of Hispanic students, and 61 percent of Asian students said they had “some” or “major” concerns about paying for college, versus just 9.2 percent of white students.

Among first-generation students,

76%

said cost of attendance is a concern.

Even as it offers free tuition in Ann Arbor to low-income state residents, Kantrowitz says top students have probably received similar offers and financial aid packages from other top universities across the country.

“There’s a sense that colleges are chasing after the same set of talented students,” he says. “And it’s not really expanding the number of students who enroll, it’s just moving them from one college to another.”

But Susan Tompor, the personal finance columnist at the Detroit Free Press, says that students don’t simply look at the package they have been offered. They consider intangibles.

“It’s important to go to a school where you have a good feeling,” Tompor says. “I wouldn’t want to be there if I felt I didn’t fit in. It’s an emotional fit, too.”

Bernstein wants to make sure future students have the same experience he was able to have. That same experience escaped his maternal grandfather, who dropped out in 1930 because he couldn’t afford to complete his degree. (See “Guest Column”.)

“There are so many barriers that stand in the way of high-achieving students and a Michigan degree,” says Bernstein. “It’s our job and our responsibility as leaders of our university to break as many of those barriers as we possibly can.”

Micheline Maynard is a regular contributor to Michigan Alumnus and recently wrote about diversity on campus. She is the former Detroit bureau chief for the New York Times.