The Legend of Opal C. Bailey

•

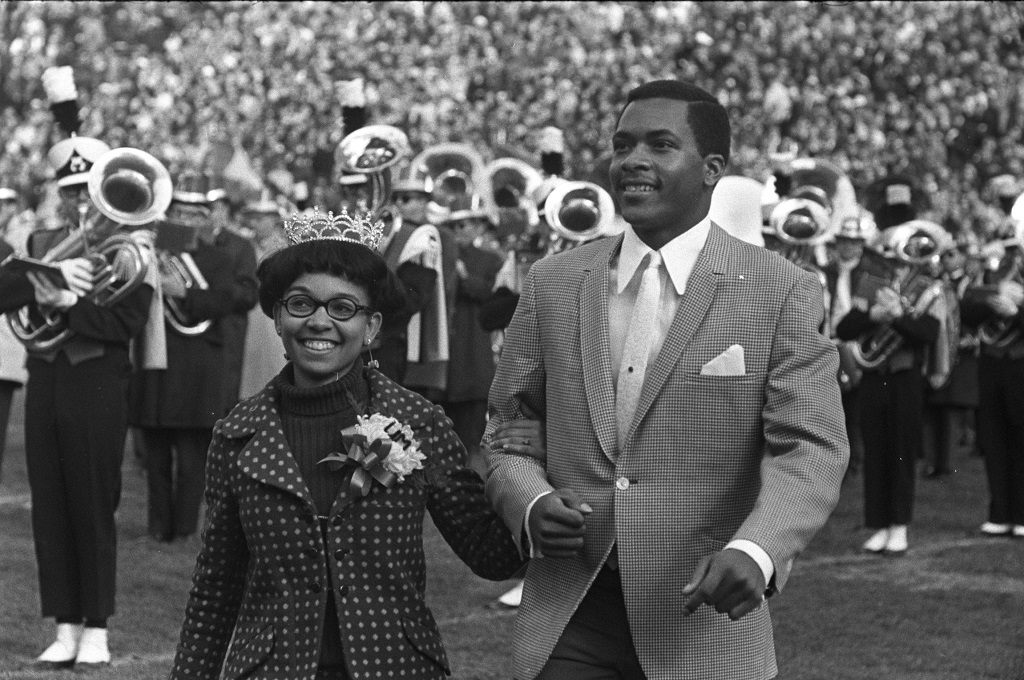

Photo courtesy of the bentley historical library

Opal C. Bailey, ’69, doesn’t remember exactly what she said to a crowd of students at the University Events Building waiting to hear who would be named homecoming queen in 1968. But she does remember the feeling of being on stage and the tone of the message.

“I do recall that I was measured, but that I was angry,” Bailey says some 54 years later. “Without being foul-mouthed or accusatory, I just remember trying to convey a sense of disappointment.”

Bailey had won the crown the previous year in 1967, becoming the first Black woman at U-M to be named homecoming queen. But 12 months later, the competition was mired in controversy.

Janice Parker, ’69, the lone Black contestant, pulled out, saying questions posed to her by the judging panel were abusive and discriminatory. In addition, University Activities Center changed the final judging criteria, downplaying talent and academic achievement — the two areas where Bailey shined a year earlier. Black student leaders believed the changes were made to make it less likely that another Black woman would win.

The new queen was set to be announced before a Dionne Warwick concert. So Black leaders on campus approached Bailey, asking her to stage a protest and refuse to crown the new queen.

“I can’t claim ownership of the idea,” Bailey says. “They approached me. I was a senior, just working hard, busy trying to get the heck out of college, to graduate.”

Before the event started, Bailey met Warwick and told her of her plans. The musician advised Bailey against the protest.

“She just didn’t want a whole ugly thing,” Bailey says.

But in front of the packed basketball arena, Bailey went through with it, explaining why Black students were protesting the contest, handing the crown over to a committee member, and walking off stage. Warwick congratulated her backstage, saying she admired her courage.

Nancy Sebold, ’69, MMUS’70, was crowned queen, and Bailey figured that was the end of it. But local and then national media wrote about the “homecoming snub,” and Bailey spent weeks being written about in the press, becoming a bit of an accidental civil rights activist.

“When you’re young, you have so much on your mind. You’re just trying to just figure it all out,” Bailey says. “One could argue that the push for civil rights has never ended. But certainly those years — oh my gosh, 1968 — forget about it. That year was just ridiculous. You know, with Dr. [Martin Luther] King [Jr.] being assassinated, Bobby Kennedy being assassinated literally weeks apart. I mean, it was just outrageous. And then the Vietnam War was going on. There was just so much going on.”

After the controversy of 1968, the homecoming queen contest was canceled and has been revived only a couple of times over the years.

Finding a Home

Born in Monrovia, Liberia, Bailey was adopted by a U.S. public health officer, who was serving in the country, and his wife. Bailey’s adoptive father later became a U.S. Foreign Service Officer, and the family moved around the world as his assignments changed.

“I appreciated being exposed to foreign cultures, traveling around the world, and living abroad, but I longed for just a place to grow up like so many kids do,” Bailey says.

She lived in Baghdad, Iraq, and then in Tehran, Iran. She begged her parents to let her attend high school in the U.S. for her senior year. So, the family packed up and moved from Tehran to Pittsburgh. While she lived in a predominantly Black neighborhood and formed lasting friendships there, Bailey did not attend the neighborhood high school. Her parents enrolled her in a predominantly white public high school across town for its top-level academic reputation. When she arrived in Ann Arbor the following fall, she found community in other Black students.

“It was the first time I had ever had that experience,” she says. “We weren’t the majority, obviously, but for me, it was like heaven. I had always been the only one or one of a few Black kids wherever I was. And here, low percentage or not, it was like a million to me.”

Bailey joined Alpha Kappa Alpha, an all-Black sorority that she says served as a base for her while she studied psychology at U-M.

Being Crowned Queen

While many universities held homecoming queen contests for years, U-M didn’t start one until 1966. Organized by the University Activities Center, fraternities, sororities, and housing units nominated women who were judged in various categories such as academic achievements, talent, personality, and beauty.

For the contest’s second year, Bailey was asked to run by the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. She says the talent portion is where she shined.

“I had killed it. Not to brag, but it’s the truth,” Bailey says. “I had killed it on talent. I even impressed myself.”

Bailey took the civil rights poem “Midway” by Naomi Long Madgett and sang it in a two-part harmony on a reel-to-reel tape. Then, during the competition, she did a modern dance to her musical performance of the poem.

Days before the homecoming football game, the competition came to a close during an event on the Diag. In dramatic fashion, the judges announced the runners-up one by one until there were two contestants remaining.

Bailey says the other finalist was from an “elite sorority” and was very involved on campus. She remembers the two of them looking at one another as the first runner-up was named, and Bailey was named queen.

“Her jaw was on the Diag,” Bailey says. “She was shocked, but I was shocked too. I never saw myself as a beauty queen.”

Bailey and the other finalists were honored at the football game’s halftime. The response to the homecoming court was muted, and later, Bailey’s sorority sisters wrote a letter to the editor of the Michigan Daily, upset at the lack of respect shown to her. There were also reports that some in the crowd booed Bailey.

But years later, Bailey says she does not necessarily believe that they were booing her because of her race. At the time, U-M didn’t have cheerleaders, and women were not allowed in the marching band, so women were generally not on the field of Michigan Stadium.

“I think it was equally as likely they were upset because we were violating Michigan tradition,” Bailey says.

The following year was turbulent in the U.S. After Dr. King was assassinated in April, Bailey found herself again on the Diag, mourning with other students.

“I just remember it was silent,” she says.

During a memorial for Dr. King on April 5 at Hill Auditorium, Bailey performed “Midway” to the crowd.

Four days later when Dr. King was buried, Bailey joined a group of students who occupied the Administration Building for several hours. The group chained themselves in, and they were demanding more funding for Black students and more Black faculty hires.

The effort was the start of increased activism by Black leaders on campus which led to the formation of the Black Action Movement and a 12-day campus strike in 1970.

Honoring Bailey

However, after earning her degree in 1969, Bailey left U-M for graduate school and forgot about her foray into activism during her undergraduate years. But her sorority sisters did not.

“We had always talked about Opal Bailey as the first Black homecoming queen,” says Lanie Dixon, ’01, MBA’16. “But there’s this whole story of activism wrapped in the mystical, magical legend of Opal C. Bailey.”

Dixon, who is also a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, says the sorority had long discussed endowing a scholarship to honor a member. The group quickly zeroed in on Bailey and started fundraising.

A total of 24 members of Alpha Kappa Alpha have donated to establish the Opal C. Bailey LEAD Scholarship Fund through the Alumni Association. The LEAD Scholars program is a merit-based scholarship that provides financial and community support to Black, Native American, and Latino students that are already accepted to the University. The first scholarship out of the Opal C. Bailey LEAD Scholarship Fund will be awarded in the fall of 2023.

Bailey says she was “floored” when she was told about the scholarship.

“As we go through life, many of us, I assume, reflect on where we’ve come, where we wanted to go, and how that matches up,” Bailey says. “And I think something like this, at least in my case, triggered a real sense of, ‘oh my gosh, I’m not worthy. Why me?’”

Dixon says she is grateful to see Bailey’s excitement over the scholarship.

“We have the chance to honor her in this way where she can be involved and share her story,” Dixon says. “A lot of times, people don’t honor folks until they die. This is something that should be celebrated now.”

She says the scholarship fund is important as the Black population at the University still is not representative of the general population of the state of Michigan, and racism is still prevalent.

“It was really loud in the ’60s, it was a little loud in the ’90s, and now with my kid, it’s just different and in subtle ways,” Dixon says. “It has shape-shifted, and I don’t think it has gotten any better, which is why, for me, doing this [scholarship] through LEAD is so important.”

After U-M, graduate school, law school, and careers as a clinical psychologist and litigation attorney, Bailey now works as a real estate agent and does pro bono work as an attorney volunteer for a family law custody clinic.

“Michigan is always in my heart,” Bailey says.

Click here to donate to the Opal C. Bailey LEAD Scholarship Fund.

JEREMY CARROLL is the content strategist for the Alumni Association of the University of Michigan.