In the early 1940s, a little-known senator named Harry Truman and a team of lawyers, including young U-M alumni, helped save the country billions of dollars. On the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, we share the story of how they did their part to help win the war.

Just 32 years old in 1941, Hugh Fulton was already an extremely successful lawyer. After earning his U-M degrees, he’d gone right to work at a top New York firm as a corporate lawyer and then on to Washington and the Justice Department, where he was the go-to guy for high-profile prosecutions.

In March of that year, the U.S. Attorney General, Robert H. Jackson, got a call from the junior senator from Missouri. Harry S. Truman had a job opening. He was forming a Senate committee to investigate government expenditures—a watchdog over the billions of dollars the United States was spending as it readied for war. Truman needed a sharp lawyer to run it. Could the attorney general recommend anyone?

Jackson immediately thought of Fulton, ’30, JD’31, and sent his young protégé up to Capitol Hill. But Fulton had concerns. Who was this senator? He called an old friend, Alexander Hehmeyer, a lawyer who worked at the offices of Time and Life magazines. “I asked a few of the Time editors what they knew about the senator and none could help,” Hehmeyer recalled years later in a letter now on file at the Truman Library.

The young attorney had another concern: “Are you going to let the chips fall where they may?” he asked Truman. “Or is this going to be a whitewash?”

“The chips are going to fall where they may,” replied Truman, who offered Fulton the job as chief counsel.

Indeed, it would not be a whitewash. Over the next several years, the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program—soon and forever to be known as the “Truman Committee”—would become one of the most successful efforts of its kind in U.S. history. Truman and Fulton, with a team of dedicated young lawyers and investigators, would become among the most feared and respected civil servants in the nation.

In December 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt warned the nation of the challenges ahead. Adolf Hitler had invaded Poland in 1939, and the United States was almost completely unprepared for the war that everyone knew was imminent.

Now, Roosevelt said, the United States “must be the great arsenal of democracy.”

In the years to come, Americans rose to his challenge with an industrial outpouring the likes of which the world had never seen. The numbers, even today, are staggering: 100,000 tanks and armored vehicles, 310,000 airplanes, 806,000 heavy trucks, 12.5 million rifles, 41 billion rounds of ammunition. The total cost was $304 billion.

Americans from all walks of life rolled up their sleeves and went to work—on the battlefield and at home. But a darker side of that effort involved corruption; mismanagement; and vast potential for profiteering, waste, and inefficiency.

Someone would have to keep an eye on it all.

With their meager appropriation, Truman and Fulton got to work. Truman gathered a strong, bipartisan group of senators to fill out the committee and set the tone for their approach. The committee would seek results, not headlines. “If something is wrong, let’s get it corrected and not make a big to-do about it,” Walter Hehmeyer heard Truman explain. “There is a war on here and we don’t want a lot of credit.” Hehmeyer, the brother of Fulton’s friend Alexander Hehmeyer, worked for the committee as an investigator and its head of public relations.

Fulton began building a small team of lawyers and investigators, mostly young professionals early in their careers and eager for public service. With office space at a premium, the staff ended up scattered around the Senate office building. Key meetings often took place in a little room, known as the “doghouse,” off Truman’s main office.

The work day began as early as 6:30 or 7 a.m. “Every morning, I would meet early with Fulton,” Truman wrote in “1945: Year of Decisions,” volume 1 of his memoirs. “We would go through big stacks of reports and letters and notes which constituted leads, some of which developed into major investigations, such as shipbuilding or housing.”

Housing—military camp construction—would be their first big target.

“In standard Truman style, the committee went to nine typical camps and conducted hearings on the spot,” Margaret Truman wrote in the best-selling 1972 biography of her father, “Harry S. Truman.” What they found, she added, was almost incredible. At one site in Pennsylvania, a $125,000 construction project had ballooned into $1.7 million. A Texas camp had swelled from $480,000 to $2.5 million. One engineering company, they calculated, was earning profits of 1,478 percent.

The committee released its first report in August 1941. As Margaret Truman wrote, “My father documented $100 million of waste in the $1 billion camp-building program.” That was just the start. Shipbuilding, aircraft construction, aluminum production, munitions, labor relations, contracting procedures. The requests and concerns poured in so fast the committee could barely keep up.

Then came Pearl Harbor. Suddenly, the committee was no longer investigating the defense program; it was investigating the war effort.

Bob Irvin, JD’41, had just passed the bar exam when he joined the committee in February 1942. For a young lawyer fresh from Ann Arbor, this was heady stuff. “To see these men who were there because of their political ability, putting the interest of the nation ahead of their own political positions, was a very, very inspiring thing for a young guy,” he recalled in a 1970 oral history interview on file at the Truman Library.

Irvin soon found himself in the middle of one of the committee’s most high-profile cases. For months, the staff had been getting letters from a foreman at a steel plant in Pennsylvania claiming all sorts of shady dealings—faulty inspections, doctored records, defective product.

“The savings in human lives can never be calculated.”

“And the stories he was telling in writing were so fantastic we couldn’t believe them,” Irvin recalled. The man sounded like a crackpot—until the day shipbuilding magnate Henry Kaiser testified before the committee. One of the senators asked him why a ship he’d just completed had broken apart as it was being readied for sea.

“Kaiser said it was the lousy steel that he was getting from Carnegie-Illinois Steel Corporation,” Irvin said in the oral history interview. Within hours, he was on a plane to Pittsburgh to interview the foreman.

Irvin and two other investigators sat down in the man’s kitchen. “And he brought out all the records to show that they were dummying up the contents of the slabs of steel that were later rolled into ship plate.” At this point, the story assumed the proportions of a spy thriller. Irvin and his colleagues began preparing subpoenas for the company’s records. Then they called the head of the steel plant on the phone.

They happened to be in town, they told him, and had heard about this plant that was “breaking all these steel production records for the shipbuilding program.” Would it be possible to arrange a tour? Sure, the man said.

Once inside, Irvin and his colleagues were able to confirm that the documents they’d seen in the foreman’s kitchen were real. They brought out their subpoenas. At that point, Irvin said, “our hospitality period came to an end, and everything turned to ice.”

By the time Irvin got back to Washington, the steel company was cranking up the heat on Truman: pressure tactics, implied threats. Truman’s response, according to Irvin, was “one of the great things about the guy. … He refused to talk to them and said he wouldn’t discuss it with them until he talked to his own people.” He backed his staff 100 percent.

As Truman himself wrote, the work wasn’t just about saving money or improving efficiency. Sometimes, lives were at stake. Such was the case of defective aircraft engines made by the Curtiss-Wright company at a factory near Cincinnati. “These engines,” Truman wrote, “were causing the death of some of our student pilots.”

He sent Fulton and a subcommittee to Ohio to investigate. Fulton took the lead in questioning Curtiss-Wright’s president, Guy Warner Vaughan, who argued that no defective engines could make it through the rigorous inspection process:

Vaughn // Well, I say there is no record of any engine that we know of—

Fulton // But now you have three.

Vaughn // I don’t know whether you are thoroughly familiar with motors, but I wouldn’t call it a defective engine in that sense.

Fulton // Would you put those three motors, with defects of the character described by Major LaVista, into an airplane?

Vaughn // No sir; not if I found them.

Fulton // And you hadn’t found them, had you?

Vaughn // Apparently not, from the records.

In 1942, and 1943, the committee’s work brought Truman, Fulton, and other members of the committee to Ann Arbor and nearby Ypsilanti. Concerns were mounting about the huge bomber plant Henry Ford had built at Willow Run; the committee had begun looking into it a year earlier. The facility, with a mile-long assembly line, had promised to churn out four-engine B-24 bombers by the thousand. Yet production had fallen behind.

One of those who appeared before the committee was George Meader, JD’31, a law school classmate of Fulton who was then the chief prosecutor for Washtenaw County and who later served the committee as assistant counsel. When the committee staff came to see Willow Run for themselves, he joined the tour.

“We were riding around in one of the sight-seeing cars they have,” Meader recalled in a 1963 oral history interview. Then, one of the Ford officials turned around and said to Fulton, “‘Well now, if you see anything wrong in the way we’re doing things here, let me know.’”

Fulton waited until the man turned away and then leaned over and whispered to Meader, “If I really wanted to be smart with this man, I would just wait until we get to the end of the production line and say ‘What’s wrong is that there aren’t enough bombers coming out of here.’”

The Truman Committee eventually criticized elements of the Willow Run operation, notably Ford’s decision to adopt an assembly-line production model, problems with contracting and materials, and the company’s inexperience at building large airplanes. However, the committee also noted that by 1943 many of these problems were being worked out.

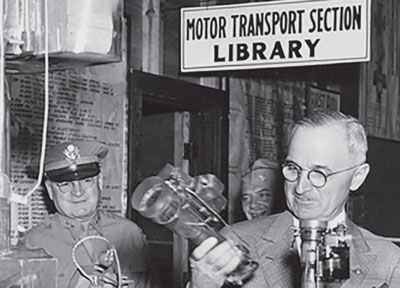

By not courting publicity, the Truman Committee attracted lots of it. The idea of saving money by checking up on the government had wide public appeal, and on March 8, 1943, Truman’s picture made the cover of Time magazine.

At first, Margaret Truman noted, Democrats, including Roosevelt, feared the criticism that might come from the committee’s actions. But they soon realized Truman was an asset. “More and more Democrats realized that the style and standards my father set for the Truman Committee had stolen all the thunder from Republican criticisms of the war.”

And so it was that with an ailing president nervous about winning a fourth term, Truman in 1944 found his name on the ticket as Roosevelt’s running mate. On Aug. 4, Truman stepped down from the committee’s leadership. Fulton resigned a few days later.

The work of the committee continued into the postwar period, but its glory days were over. The heart of its work had come from the successful partnership of the two men.

“Hugh Fulton was as much responsible for the success of the Truman Committee as any one individual,” recalled Herbert Maletz, one of the staff investigators, in a 1968 oral history interview. Truman often said of his chief counsel that Fulton had a “brain almost as big as his body.”

At the end of the day, both men could look back with pride. Over its seven-year life, the Truman committee held 432 public hearings and issued 51 reports totaling almost 2,000 pages. Truman and Fulton had overseen 32 of those reports.

By most estimates, the committee saved the country billions of dollars, while spending less than $1 million to do so. The savings in human lives, or the military benefits on faraway battlefields, can never be calculated, nor can the work that never made it into a report. Often, just a phone call or the threat of an investigation was enough.

Beyond those numbers is an equally impressive accomplishment. Truman had set—and achieved—a goal that, from the perspective of the toxic political climate of Washington today, seems incredible: Every single one of the Truman Committee’s reports was unanimous.

One of the committee’s young lawyers, Wilbur Sparks, summed it up in a 1968 oral history interview: “History may very well show that never before or since has there been a congressional committee which conducted itself in such a nonpartisan manner.”

It was a time—however brief—when the government, and Washington, worked.

Steve Drummond is a senior editor at National Public Radio in Washington, D.C. A former newspaper reporter and teacher, and a three-time U-M graduate, he lives in North Bethesda, Maryland.