It is easy to look back on our University forebears and think of all the traditions and standards they started. But they were as prone to missteps and mistakes as generations before (and after) them. Take, for instance, the 1908 episode at the Star Theatre.

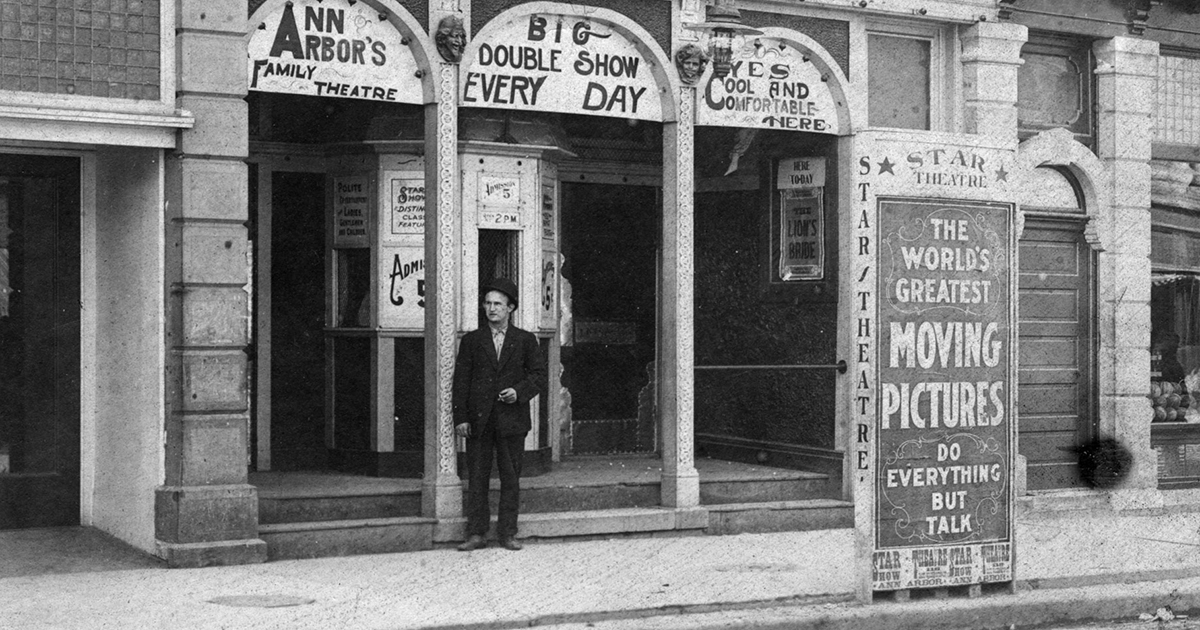

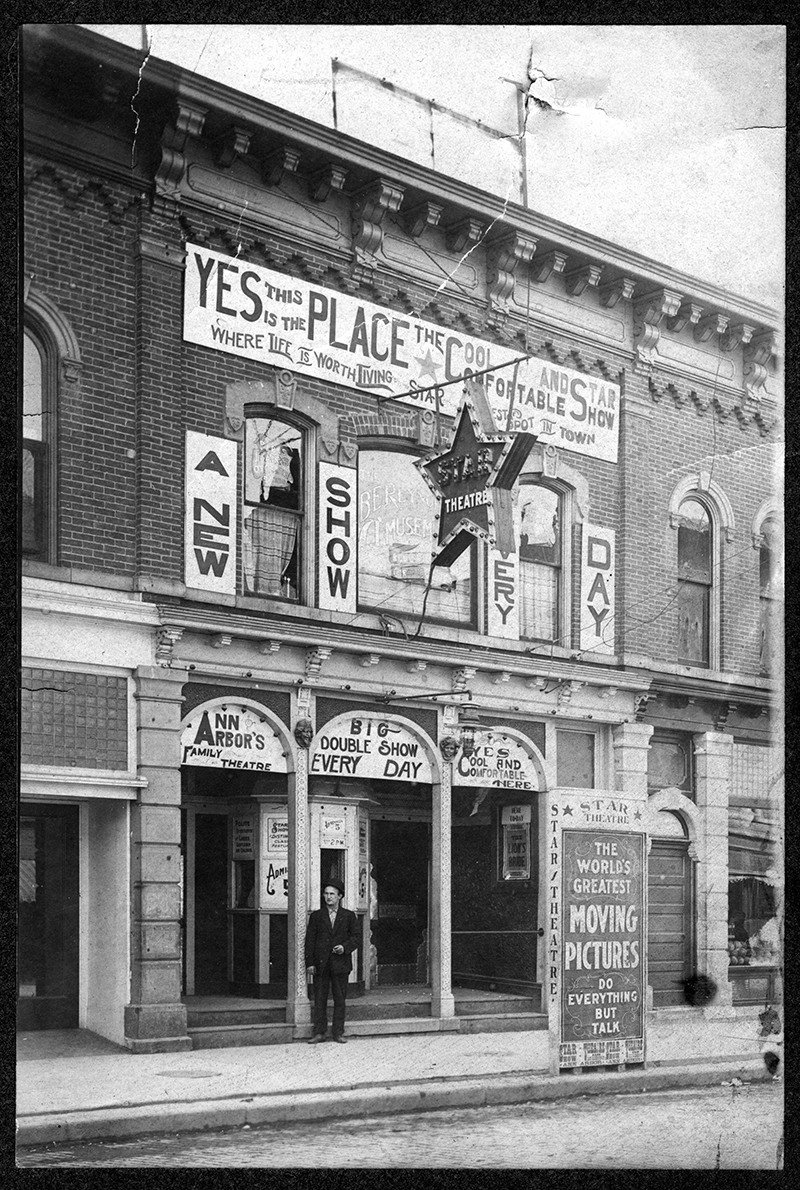

In the early 20th century, a nickel was enough to get you into a hole in the wall for a film—silent, of course. Albert Reynolds set up such a venture, the Star Theatre, in August 1907 at 118 East Washington St., near where the Ann Arbor Brewing Company and other businesses presently reside. The Star was one of a wave of new, low-price movie houses vying for local dollars and cents. It was also one of the few that possessed a stage for live vaudeville acts, giving it a competitive edge.

Less than a year later, however, the theater stood decimated, the victim of one of the largest riots in Ann Arbor’s history. On the night of Monday, March 16, 1908, at least 1,000 students took to shattering the Star’s windows, ripping out signs and seats, destroying the resident piano, and causing general mayhem.

U-M President James B. Angell and at least one dean, Harry B. Hutchins of the Law School, temporarily quelled the mob with appeals for everyone to disperse. After listening peacefully, the students continued their rampage.

The following morning, the Star Theatre was a shell of its former self. Police apprehended 22 students; 18 were formally charged. Miraculously, no one sustained serious injuries.

In the aftermath, Angell testified as a witness and spent many hours at the courthouse. Three of the students pleaded guilty to loitering, each paying a $4.65 fine (almost $120 today). Local businesses paid for the remaining 15 students’ bail: $1,000 per student (now over $25,000 each). The student council negotiated the dropping of charges in exchange for paying the estimated $2,500 in damages ($65,000) to repair the theater. They raised the money via collection drives from the student body. The Star then rebounded and continued operating until 1919.

Due to the riot, U-M’s reputation took a beating nationally, even though theories abounded that the students’ behavior (while inexcusable) was prompted by other, equally murky, events:

- The Cornell Daily Sun reported on March 18, 1908, that a “special policeman” assaulted a student for “minor disturbances” on the Saturday before the riot, sparking an uproar two days later. The Ivy League newspaper reported that the Michigan militia was summoned after U-M students marched from a housing district to their target, chanting “All out for the Star Theatre” along the way. Local police and firefighters were allegedly no match for the mob.

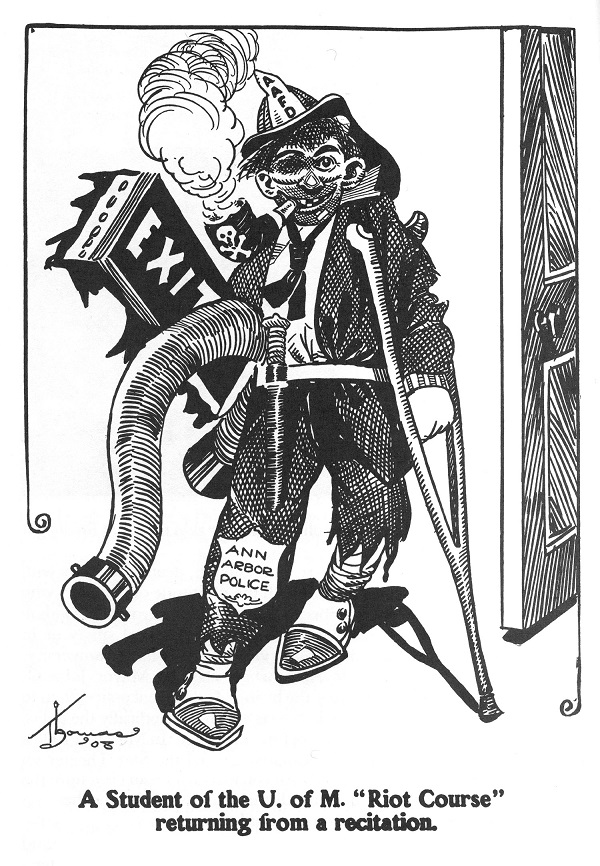

A 1908 cartoon lampooning the riot, source unknown. Courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library. - Two Ann Arbor News articles published decades later (one in 1936, the other in 1942) told a different story. In their version, earlier in the day on March 16, a man named Jacob Slimmer—an usher/narrator/guard at the Star—took offense to a comedic interruption during a show and assaulted a pair of students. The students swiftly rallied and delivered the reciprocal riot that night. This report claims that up to 3,000 students were involved. No one knows what became of Slimmer, but, reportedly, Albert Reynolds and his wife hid in the basement under police protection.

- The 1967 Michiganensian had this to say: At some point prior to that Monday, Reynolds lost patience with student “discourtesies” and announced he no longer wanted their patronage. Students retorted by smearing the theater with eggs and produce, which spiraled into the complete destruction of the venue.

- In 1991, Jonathan Marwil’s “A History of Ann Arbor” seemed to corroborate the Michiganensian’s account, stating that the riot occurred because the Star ejected several students the prior night, leading to the riot.

- “True Crimes and the History of the Ann Arbor Police Department,” written in 2002 by retired Ann Arbor Police Department Lt. Michael Logghe, gave an entirely different, sports-related reason for the riot. Months earlier, Reynolds approached a star U-M football player with a proposal to fix a game. The player was told if he played poorly, the two men could make money by betting on the likely loss. The athlete refused, and the matter was kept quiet, or was simply unknown, until the week before the riot. When students learned of the attempted bribe, they called for the Star Theatre to close. Their demand unheeded, a mob formed and marched to the Star, calling for Reynolds to come out. He, naturally, thought otherwise as he fled through the back door. With the Star’s owner nowhere to be found, the assembled students destroyed the establishment instead.

Whatever the case, one thing is certain: if alive today, Albert Reynolds would opt for a bombardment of one-star Yelp reviews over the bombardment of bricks.

Gregory Lucas-Myers, ’10, is assistant editor of Michigan Alumnus magazine.