Almost a century ago, Wolverine football coach (and future athletic director) Fielding Yost had a vision for a stadium grand enough to rival any professional venue, emblematic of the University’s winning tradition. In the process, legend has it, the swampy earth claimed an excavation crane that remains buried there.

One account, generated at some unknown point, holds that workers had left the vehicle in the mud at the end of the day on a Friday, only to return to it swallowed up on Monday. However, this story may simply be a persistent tall tale.

In fact, let’s get this out of the way: there is probably no construction equipment—of the heavy, vehicular sort, anyway—under Michigan Stadium’s famous turf. Tellers of the story even differ on what, specifically, that equipment was: sometimes it’s a crane, sometimes a steam shovel or a bulldozer.

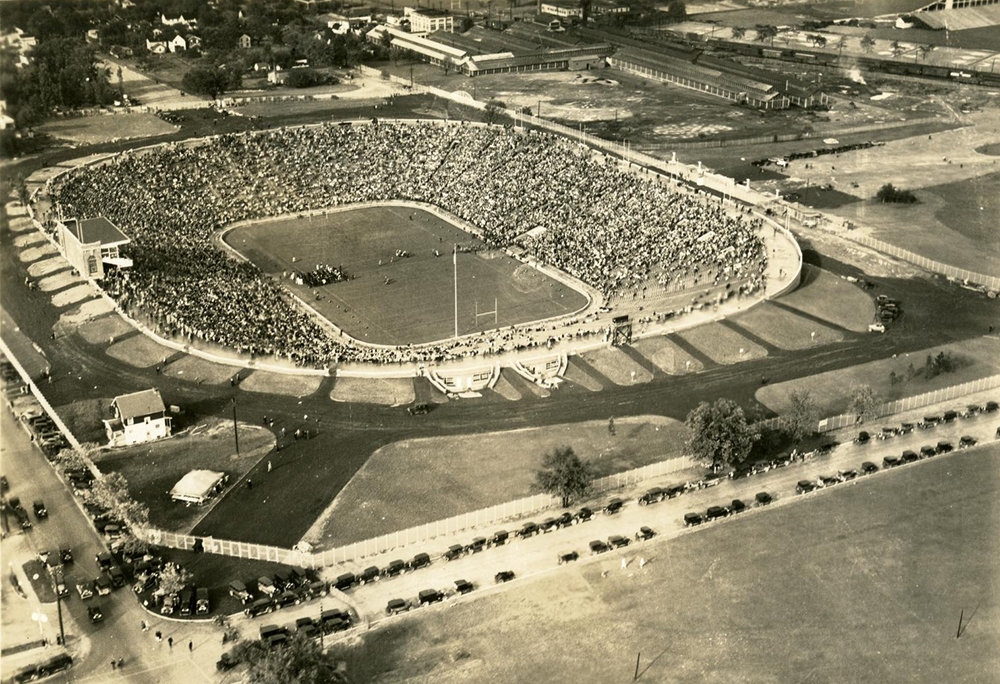

The late 1910s and early 1920s brought a surge of football popularity to the U.S, and the University was no exception. In 1914, the U-M board of regents approved a proposal for enlarging Ferry Field, the home stadium at the time. However, costs and the major disruption of World War I stamped out any grand plans.

In 1920, the regents appointed engineering professor James Cissel to study the issue of Ferry’s capacity, and he concluded that a new facility was needed. Surprisingly, Yost was initially skeptical of the idea. Having visited Harvard Stadium, the Yale Bowl, and Princeton’s Palmer Stadium, he was wary of both costs and increased city traffic. By 1923, though, he had warmed to the idea simply because of the sport’s rising popularity. The wheels truly began to turn, and digging began in 1926.

Thus, we come to the elusive “crane.”

The Michigan Stadium site had a high water table, the level at which groundwater begins to saturate the soil. Excavators brought in pumps and set up an array of drainage systems, but the problem worsened when natural springs were uncovered. As delays and obstacles kept piling up, the area even garnered a nickname: “Tillotson’s Pond,” after Athletic Department business manager Harry Tillotson. Coincidentally, Ferry Field had also experienced construction issues around its high water table.

There appear to be no records in the news, financial accounting, or otherwise hard evidence of such an extraordinary event as a sunken crane. Crews moved immense amounts of soil around the clock—around 2,000 cubic yards a day—so a lost vehicle would be a major hindrance.

Whether the lost equipment is purely Michigan mythology or everyone involved took a vow of silence about the matter, the hard work continued. Digging concluded, concrete settled, all the boxes were checked, and Michigan Stadium opened on Oct. 1, 1927.

The total cost: $1,131,733.36 (comparable to over $16 million in 2018).

Gregory Lucas-Myers, ’10, is assistant editor of Michigan Alumnus magazine.