When Taylor left her hometown of San Diego to attend U-M in 2014, she was filled with excitement for her freshman year. “I was ready for a change,” she remembers. “And for me, going so far from home felt like a new start.”

Yet, once in Ann Arbor, her enthusiasm turned to homesickness. “It was the first time I had been alone. I didn’t have any friends,” recalls Taylor, who requested her last name not be published. Reaching out to her old high school buddies, together at colleges in California, did not help. “Those were the times when I felt the most isolated.”

Adding to her sinking emotional state were the rigors of a pre-med curriculum. “I’m a perfectionist. So it was really hard to not get good grades at Michigan. I remember getting an A-minus and thinking it was the end of the world.”

But what troubled Taylor the most was a past mental health issue she thought she had conquered. “Once you start, it becomes an addiction,” she explains of the self-harm she began practicing in high school (at times cutting herself twice a day, every day). “No one noticed,” she says, adding that she hid the scars under longsleeved shirts and bracelets. “I thought it was my fault that I was sad.”

It was not until her senior year of high school—when her friends intervened— that Taylor started to see a therapist and take an antidepressant. Her mistake at U-M, in retrospect, was not understanding how college would be “a completely different world than high school” and that seeing a therapist from her earliest days on campus might have prevented her setback.

Instead, she suffered in silence as her mental health issues, revolving around social and academic insecurities, began to re-emerge. She describes the symptoms, “I can’t get out of bed. It’s a mixture of anxiety, exhaustion, and sadness that confines you to the bedroom. For me, it’s easy for small, negative thoughts to build on themselves and progress to darker and darker thoughts.”

In October of her freshman year, fearing she would begin cutting herself again, she found help through U-M’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), located in the Michigan Union. After an emergency appointment, she was quickly connected with a therapist. “I was pretty worked up. The counselors I saw there were very good at bringing me back to a base level and connecting me to resources.”

Now a junior, Taylor says she is taking “baby steps” toward happiness, following a new diagnosis of bipolar disorder. She sees a therapist regularly and is on a new, more effective, medication. “CAPS was really crucial to me even staying in college. If I didn’t get help, I think I would have completely spiraled.”

Taylor is not alone in her suffering. Mirroring a national trend in higher education, CAPS has seen a dramatic increase in the number of students seeking its services. During one particularly busy period during the fall 2015 semester, CAPS saw a 40 percent increase from the previous year, with some 200 to 250 students signing up each week for first-time appointments. By the end of the academic year, roughly 10 percent of the student population had sought help from CAPS for a mental health issue.

“That’s unprecedented,” says Todd Sevig, who has worked at CAPS for 26 years—16 of them as the director. To meet demand, CAPS increased its number of full-time licensed counselors this year from 30 to 37. They include psychologists, social workers, and psychiatrists. Different counselors have various areas of clinical expertise—from sexual assault and alcohol/ substance abuse issues, to anxiety and eating disorders—but they are also all “generalists,” able to help whoever walks through the door.

Sevig says the added staff have greatly reduced what was once a two-week waiting period for students and has enabled the most urgent cases to be seen more promptly. Additionally, CAPS entered a partnership last year with ProtoCall, a mental health hotline, to ensure students have access to a licensed psychologist even when CAPS is closed. During the first 10 months, an average of 59 students a month called the phone-counseling hotline. As of last spring, the after-hours phone number is emblazoned on the back of every newly distributed student identification card. This means that all incoming students and every successive class—as well as those getting replacement cards—have the lifeline at their fingertips.

To make sense of the surge in student patients across the country, Sevig sites a number of possible factors, one being the effectiveness of educational mental health campaigns. Less stigma around the issue means more students are seeking services. But, in turn, says Sevig, “it has created a scenario where there is more demand than supply.” The CAPS director also speculates that helicopter parenting could impede students’ ability to be resilient when faced with an increasingly stressful academic and economic environment. But he also worries that success has become too paramount in students’ minds. “When we say, ‘Leaders and Best,’ the expectations are higher. The message also comes from parents, family, and friends,” he says. “Students don’t feel like they can fail or drift.”

That was certainly true for Will Heininger, ’11, a former Wolverine football player, whose depression—sparked by his parents’ divorce— came on suddenly in the summer of 2009, following his freshman year. “My mom was in a new house, and my dad was in Chicago. Within 10 days, I felt like my life had slipped upside down. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t chew and swallow food. I had awful days where I wondered why I was alive,” he says. “I would cry my eyes out to my mom on the couch.”

Heininger tried to conceal his illness from his teammates. “I thought, ‘I’m a big, tough football player. If people find out, I might get kicked off the team and lose my scholarship.’” When he finally broke down during practice that August, a concerned trainer immediately took him to see an athletic department counselor and clinician. “She saved my life,” says Heininger, who is now a PhD student in U-M’s School of Public Health.

Anyone who crossed the diag on Sept. 17, 2015, could not have helped but notice an unusual exhibit spread out over the lawn—a colorful collection of more than 1,000 backpacks, many with photographs, letters, and essays attached to them. Titled “Send Silence Packing,” the display was organized by the University’s chapter of Active Minds, a national organization that has been at U-M since 2014 and aims to raise mental health awareness on college campuses. Each backpack represented one of the roughly 1,100 college students across the country who die by suicide each year. Active Minds is now just one of nearly a dozen student organizations the University is partnering with and supporting. (See the sidebar below.)

“It was an emotional day,” says senior Aparna Yechoor, a board member on Active Minds. “All day, people would come by, stop, look at the backpacks, and read the stories. Then they would ask what it was.” She explained to them that Active Minds offers educational and awareness-building events for students, while also hosting fundraisers for mental health advocacy. “We want people to come together to learn and talk about mental health. It’s hard to find your place here, given the elite level of students. When you feel your peers around you are feeling those same feelings, it helps bring you out of isolation.”

For that same reason, in 2014, three years after graduating, Heininger offered to make a video for Athletes Connected, an organization that had just launched and aims to reduce stigma and promote positive coping skills for U-M student-athletes. Developed with initial funding from the NCAA Innovations in Research and Practice Grant program, it remains a unique collaboration of the U-M School of Public Health, the Depression Center, and Michigan Athletics. After the first screening of Heininger’s video, 40 student athletes requested a counseling appointment. Of those, 33 ended up in treatment.

Similarly, Taylor made a video last winter for CAPS In Action. It was one of 13 “Leaders at Their Best” videos produced by the now 1-year-old student CAPS group. In each video, a student openly discusses how he or she overcame mental health struggles, again to decrease stigma and encourage students who are suffering to come forward.

“None of my friends knew about my struggles before the video,” says Taylor, who kept her issues well-hidden. “It was a huge part of my life to be dealing with these depressive episodes.” But after the video was posted on the CAPS website, Taylor was pleasantly surprised by what happened next. Friends at U-M—whom she had never realized were also struggling—opened up to her about their issues. She was then able to deliver, firsthand, the heartfelt advice she had shared in her video.

“If you feel out of control or that your thoughts are detrimental to you, if you think this is not who you should be or are, talk to someone. People are here to help,” she says in the video, staring straight into the camera. “They really are.”

Students Helping Students

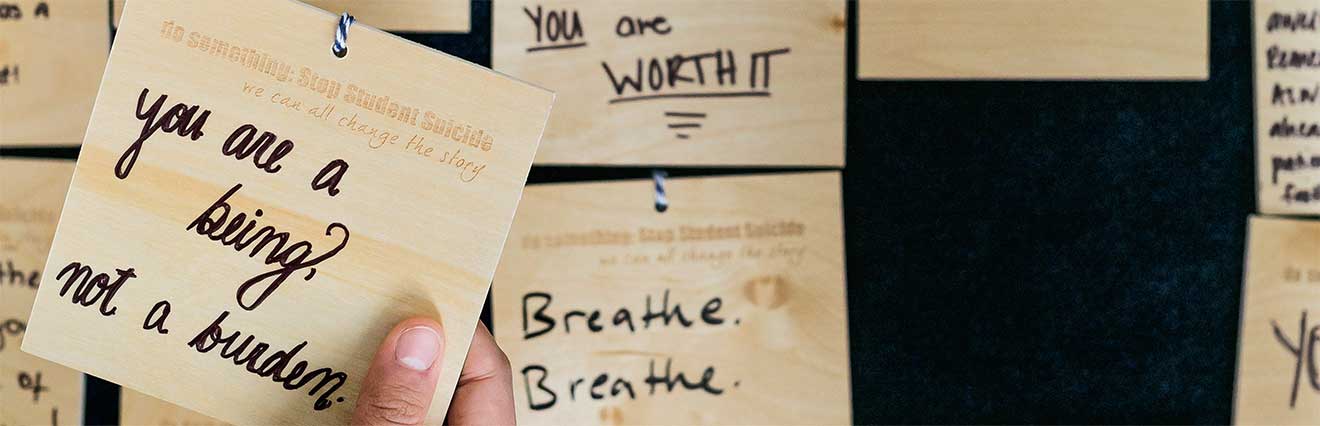

Messages of Hope is a CAPS In ACTION campaign in which students are encouraged to write a positive message on a tile and leave it on the wall outside the CAPS offices. Anyone struggling and in need of inspiration is invited to take a tile home or hang it somewhere on campus. Recent messages include: “If you change the way you look at things, the things you look at will change.” The images are also posted on the group’s Facebook page.

Wolverine Support Network (WSN) is a joint initiative of Central Student Government and CAPS. Now in its third year, WSN offers 20 confidential support groups run by a total of 60 student leaders trained by CAPS to help destigmatize mental health issues. It also holds social events, like bowling and laser tag outings. The first semester WSN was in operation, 75 participated in groups; by the end of the first year that number had grown to 150.

Awaken Ann Arbor is a student organization hosting weekly meetings for drop-in meditation workshops. Its aim is to teach students how to meditate and take consistent action toward personal and spiritual growth, while also encouraging them to think for themselves.

National Alliance on Mental Illness on Campus is a student-led mental health policy organization that aims to tackle issues on campus by raising awareness and educating the community. With a special focus on advocacy, the group currently works with CSG on an initiative that would allow students with mental health issues to register their medical details with their professors to decrease anxiety and increase leniency.

Julie Halpert, ’84, is a freelance journalist for publications including The New York Times, Family Circle, and The Wall Street Journal. She also blogs for The Huffington Post and teaches journalism in U-M’s Program in the Environment.

Editor’s Note: Following publication, a subject interviewed for this article requested that her last name be removed for privacy reasons. Michigan Alumnus updated this version to reflect that change on July 16, 2019.