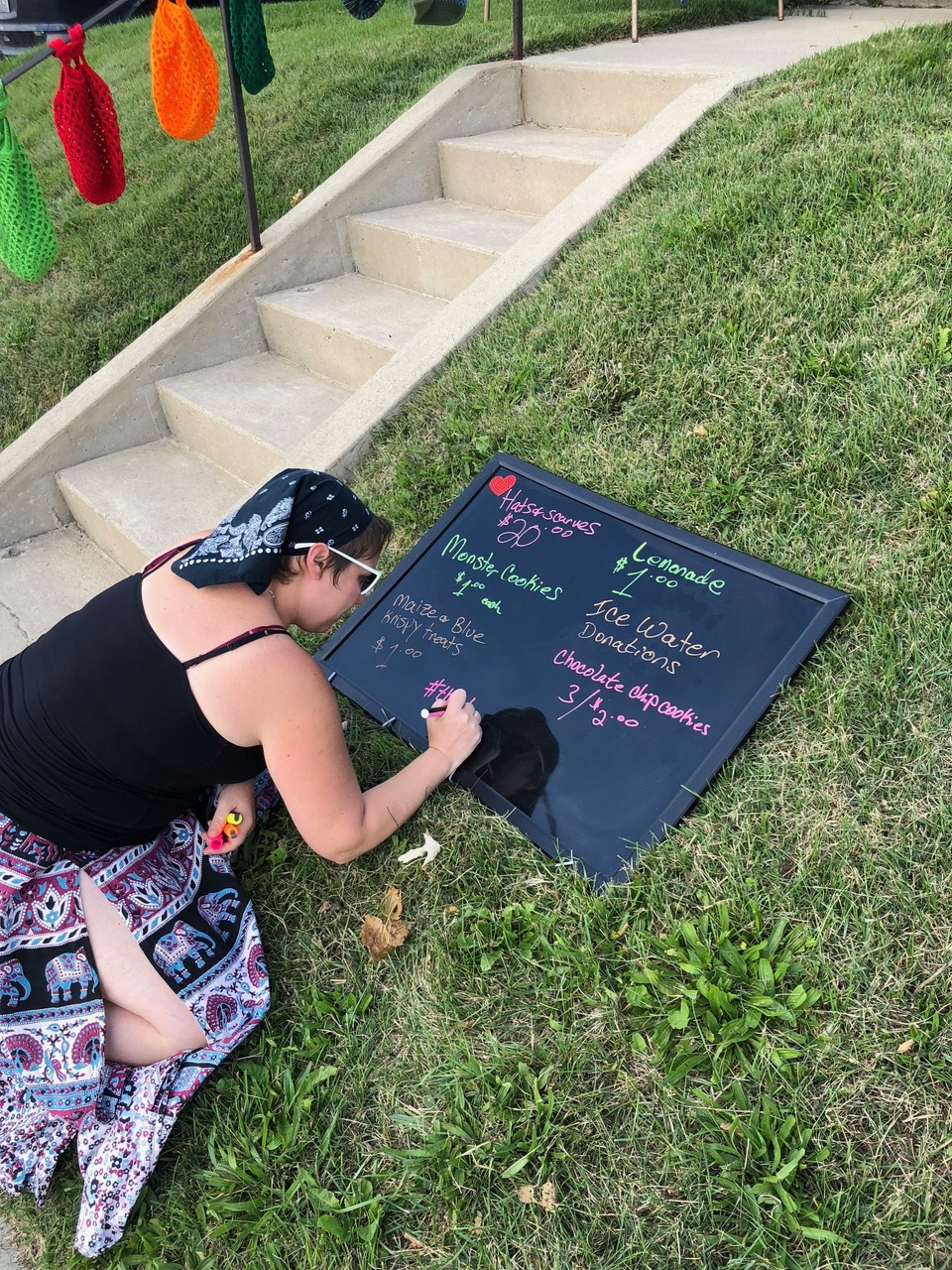

Around noon on the steamy mid-September Saturday when the Mustangs of Southern Methodist University galloped into Ann Arbor to take on the Wolverines at Michigan Stadium, Elizabeth Ricciardi was making last-minute changes to the black glass board propped up by the steep hill leading to her stoop on West Stadium Boulevard. Written beneath the listings for $20 UM-themed hats and scarves that she had handmade and the $1 lemonades her two kids are hocking, she added: “Maize & Blue Krispy treats $1.00,” along with her Instagram name. “I couldn’t do anything chocolate or with frosting because it would melt in this heat,” Ricciardi explained. “But people are going to want snacks.”

It was more than three hours from kickoff, but Ricciardi’s landlord is busy on the side of her home, guiding about a dozen vehicles into rented spaces in the yard. The income generated, Ricciardi theorizes, allows him to rent the house to her at an affordable price. And across the street, Pioneer High School’s parking lot was a frenetic, festive plain of Michigan colors brought by the masses who paid $50 per space for the day.

For miles around Michigan Stadium, the pop-up economy of home games is in full swing as more than 100,000 fans must park, eat, sleep, and party. The usual infrastructure of Ann Arbor simply can’t suffice; there aren’t enough parking spaces, hotel rooms, or quick ways to grab cheat eats to accommodate the hoards who flood in for seven or eight Saturdays a year from September to November.

While there’s little concrete data on the spinoff effect, it is evident that these weekends are a big opportunity for a lot of people. The most recent study of the general economic impact of Wolverine football commissioned by Destination Ann Arbor (the local convention and visitors bureau) focused on the 2013 season. It found an official windfall of nearly $82 million in economic activity. What’s more, the Ann Arbor/Ypsilanti Regional Chamber says 31 percent of the 3.7 million visitors to the greater Ann Arbor region annually come to “experience U-M athletics,” spokeswoman Margaret Wyzlic said.

That critical mass has birthed both a widespread homespun entrepreneurism as well as at least one durable business startup, ParknParty.com. Taylor Bond, ’83, MA’88, founded the site seven years ago to organize the weekly mayhem by providing an online portal for game-goers to reserve spaces for vehicles and tailgating. Most of the largest lots—Pioneer High School, Fingerle Lumber Co., Ann Arbor Golf & Outing Club—appear on the site along with hundreds of private addresses where renters or landlords are offering their yards and driveways.

Amenities vary widely; Fingerle, a lumber yard, provides power for RVs; some sites have Wi-Fi, barbecue pits, or portable toilets; and Bond’s own lot at South Main Street and Ann Arbor-Saline Road includes an indoor lounge with couches, bathroom facilities, and free drinks and snacks. ParknParty, which also provides tailgate planning and cleanup services, has now expanded the model originated in Ann Arbor to college towns in six other states, including at the University of Alabama, Notre Dame, and Louisiana State University.

“Ann Arbor is unique, though, because the reason why this pop-up economy exists and is so lucrative for so many people is because the stadium is located in the neighborhoods,” Bond said. “If the stadium was located in the middle of Central Campus, this pop-up economy wouldn’t exist.”

It all amounts to a windfall for the likes of Ricciardi, a part-time property manager who has parlayed robust game-day sales of snacks and crocheted garments into a year-round side gig. She’s baked for weddings and church coffee klatches and sells team-themed hats and scarves on Etsy. As for the games, she prefers a mid-afternoon to noon start time, she said, because people come earlier and stay longer.

“People walk back and forth between the parties, and they pass you a few times, and then after a few beers they go, ‘Oh, cookies!’” she said. “But it’s actually fun to come out and watch the spectacle at any time. It makes me feel like a little kid sometimes.”

Steve Friess is a Michigan-based freelance journalist and a 2011-12 Knight-Wallace Fellow at U-M. His work appears regularly in The New York Times, The New Republic, Playboy, and many others.