Embracing AI

•

illustrations by olivia lenhart

University of Michigan economics student Julian Barnard remembers his instructors’ pleas at the end of the fall 2022 semester.

“Leaning into the honor code was common around that time,” he says. “Three of my social sciences professors said, ‘I don’t know how to tell if you use this thing on your essays, but please don’t.’”

That thing: ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence tool that was developed by OpenAI. Users can give the chatbot a prompt and it spits out human-like text.

“ChatGPT is pretty good at generating ideas for arguments and very good at stringing together words; it’s not good at showing its work or citing sources, and it’s frequently wrong, with no remorse.”

--Tessa Tinkle

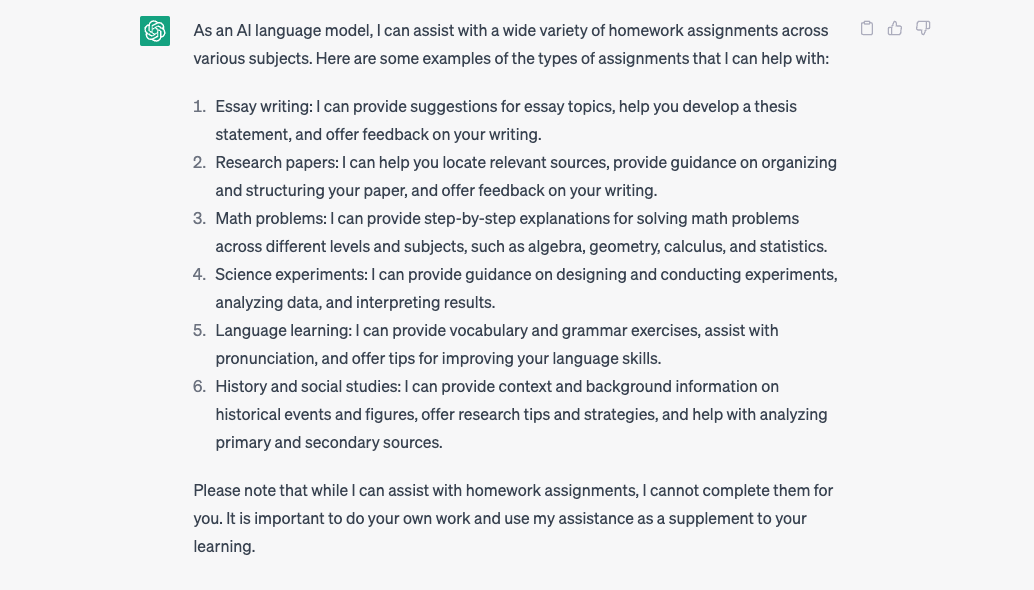

The fear of misuse and academic fraud was rampant after its release. Ask it for a 500-word essay on “Romeo and Juliet,” and a ready-made paper is done in seconds. It can provide step-by-step explanations for solving math problems across different levels and subjects, guidance on designing and conducting science experiments, analyzing data, and interpreting results.

Quickly, leaders at U-M began to take a closer look.

“ChatGPT is pretty good at generating ideas for arguments and very good at stringing together words; it’s not good at showing its work or citing sources, and it’s frequently wrong, with no remorse,” explains Tessa Tinkle, director of U-M’s Sweetland Center for Writing.

Despite the early worries that student papers would be indiscernibly generated by AI, ChatGPT’s fabrications have been easy for instructors to spot thus far, she says, and platforms such as Turnitin can help with fact-checking. Since ChatGPT generates a limited number of responses to most prompts, papers built on its output are likely to sound similar.

In the words of the bot itself: “Errors in ChatGPT’s responses result from its programming, limitations, or training data.”

Now, conversations are less about the fear of AI-written assignments and more about how students and instructors can leverage tools like ChatGPT to enhance learning.

Getting Creative

“What can I have it do that’s hilarious?” Ali Shapiro, MFA’12, a writing instructor at the Stamps School of Art & Design, admits this was her initial reaction to ChatGPT. She put it to work penning poems about pasta.

While ordering AI to do tricks isn’t inherently educational, it can forge connections among learners and foster a spirit of experimentation. This spirit thrives in ARTDES 129, Shapiro’s writing course for first-year students. The moment ChatGPT arrived, the class wanted to discuss it.

“Instead of following the day’s lesson plan, we played with the AI,” Shapiro recalls.

When students asked ChatGPT how it would write a classmate’s trend-analysis paper, they immediately found flaws in the essay it generated.

“They were very articulate about the writing’s weaknesses,” Shapiro says. “This isn’t always the case when I ask them to critique each other’s papers.”

For a subsequent assignment, she gave the class a choice: revise the rough draft using feedback from peers and the instructor, or use ChatGPT to revise, describing how it was used, sharing screenshots from the process, and explaining what was interesting about it.

Shapiro argues that the better a student understands what they’re being asked to do, the more effectively they can use a tool like ChatGPT. She says one graduate student that she works with uses ChatGPT like a tutor.

“He has ChatGPT ask questions about the topic he’s writing about, to help him find gaps in his knowledge,” she explains. “Ultimately, learning how to write is learning how to think, and it seems like AI can be helpful for doing that even better.”

Reevaluating Instruction

Matt Kaplan, executive director of U-M’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, advises instructors to think hard about why they assign papers and essays, and to share the purpose of these assignments with students.

“Talking to students about academic integrity and having clear expectations for citing sources, these kinds of things can help prevent some of the problems we worry about with ChatGPT,” he says.

Giving students multiple chances to demonstrate what they’ve learned is important, too, Kaplan adds. For example, an instructor can ask them to share key moments in their term-paper research process.

Emily Ravenwood, who manages instructional design teams at LSA, uses annotated bibliographies for this purpose.

“With this approach, the instructor might have students describe the sources they plan to use, or share outlines showing where different sources will be used to support their arguments,” Ravenwood says. “These skills are a big part of what we’re trying to teach with research papers, and things ChatGPT can’t do.”

Ultimately though, she says faculty curiosity and creativity will make AI-powered tools an instructional asset for years to come.

Some have suggested turning back to the clock to use timed, handwritten essays completed in class to circumvent the potential misuse of AI. But Ravenwood, Kaplan, and Tinkle all agree that this isn’t a good approach.

Those types of high-stakes assignments can create barriers for students with disabilities and those who aren’t fluent in English, while low-stakes assignments ease the overwhelm that may encourage students to seek out shortcuts.

Knowledge is Power

In an effort to tackle the challenges that AI will bring to higher education, U-M has formed the Generative AI Advisory Committee to create University-wide recommendations about tools such as ChatGPT. Its 18-member roster includes U-M faculty, staff, and students, and represents a broad range of academic disciplines, including medicine, business, engineering, and English.

“The goal is to leverage these technologies and empower us to use them the right way across all three campuses,” says Ravi Pendse, U-M’s vice president for information technology and chief information officer. “We want our students to be leaders, and the only way they can lead in this space is if they’re educated about it. For that to happen, we need to be educated about it, too, so we learn from each other and talk through the issues we’ve been hearing about.”

These issues range from how to know if a paper was written by ChatGPT to how facial recognition technologies can misinterpret dark skin if their training data lacks racial diversity.

The committee, which first convened in April and was publicly announced in May, also asks outside experts to help them explore AI-related research, grapple with ethical questions, and understand the ways the tech is evolving — and transforming the learning process.

“We want our students to be leaders, and the only way they can lead in this space is if they’re educated about it."

--Ravi Pendse

In addition to sitting on the committee, staff from the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching and the Sweetland Center for Writing host workshops for faculty who want to unlock ChatGPT’s classroom potential while avoiding its pitfalls.

Anne Curzan, MA’94, PhD’98, dean of LSA, says she agrees with the approach of using it as a teaching tool.

“I am of the school [of thought] that we incorporate this into classrooms and teaching and learning as opposed to trying to pretend it’s not there or trying to catch students for using it. It’s a tool, like so many other technologies, although a very powerful one,” she says. “AI can do many things from OK to well. But there are human things it can’t do particularly well. AI is something we will continue to learn to use as writers and researchers, and it is a technology that we need to think very critically about in terms of its ethics and implications for us as humans and human societies, far beyond the classroom.”

U-M Alums are Supporting the AI Products Schools Will Use in the Future

As a founding partner at Reach Capital, an ed-tech venture-capital firm, Wayee Chu, ’97, meets the founders of companies developing AI teaching and learning tools, then helps decide which to fund and nurture.

She also collaborates with faculty teams at several universities, including researchers from Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI.

When considering what to fund, Chu, who is a member of the Alumni Association’s Board of Directors, tries to determine what drives the people behind the products and how this motivation shapes their approach to problem-solving.

“When investing in any new tech, it’s important to understand the context its creators are coming from and what problems they’re trying to solve,” she says. “The way a product functions matters, but what company founders value – and how they put those values into action – matter more.”

TeachFX, a company from Reach Capital’s portfolio, does this well with help from AI. Teachers record upcoming lessons on an app, which analyzes metrics related to classroom conversation. The AI offers personalized, objective feedback designed to empower.

“Research has shown that the more student talk a lesson produces, the more classroom engagement there is, so metrics like the percentage of teacher talk versus student talk can be very valuable for educators,” Chu says.

Providing this kind of analysis to multiple teachers, multiple times per day, isn’t feasible for a human, but it’s no problem for AI. And the insights teachers receive help them celebrate their students’ success — not to mention their own. According to Chu, all of this is a recipe for personal and professional growth.

JESSICA STEINHOFF is a freelance writer based in Wisconsin.