From catastrophic flooding in historic Venice to seemingly endless wildfires in California towns, the effects of climate change are no longer a matter of speculation but of day-to-day reality.

There is, however, a lot unknown about the future—including whether we can reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to avoid the worst-case scenarios.

U-M is home to experts across multiple disciplines who are devoting their careers to tackling the challenges of climate change. We talked to six of them about what lies ahead—and what can be done to ensure the best possible outcomes for future generations. Interviews have been condensed and edited.

The Paris Agreement set a goal of no more than a 2-degree rise in global temperatures. What happens if we don’t make it?

Richard B. Rood, a professor of climate and space sciences in the College of Engineering, teaches several courses about climate change and focuses his research on solutions.

I think we need to do everything we possibly can to meet the goal, and even 2 degrees is really quite dangerous. But there’s currently no evidence to suggest that we will make it. So we need to start thinking about how we are going to meet some higher goal, and a number that I have frequently used—just to start thinking about it—is 4 degrees.

I think we need to do everything we possibly can to meet the goal, and even 2 degrees is really quite dangerous. But there’s currently no evidence to suggest that we will make it. So we need to start thinking about how we are going to meet some higher goal, and a number that I have frequently used—just to start thinking about it—is 4 degrees.

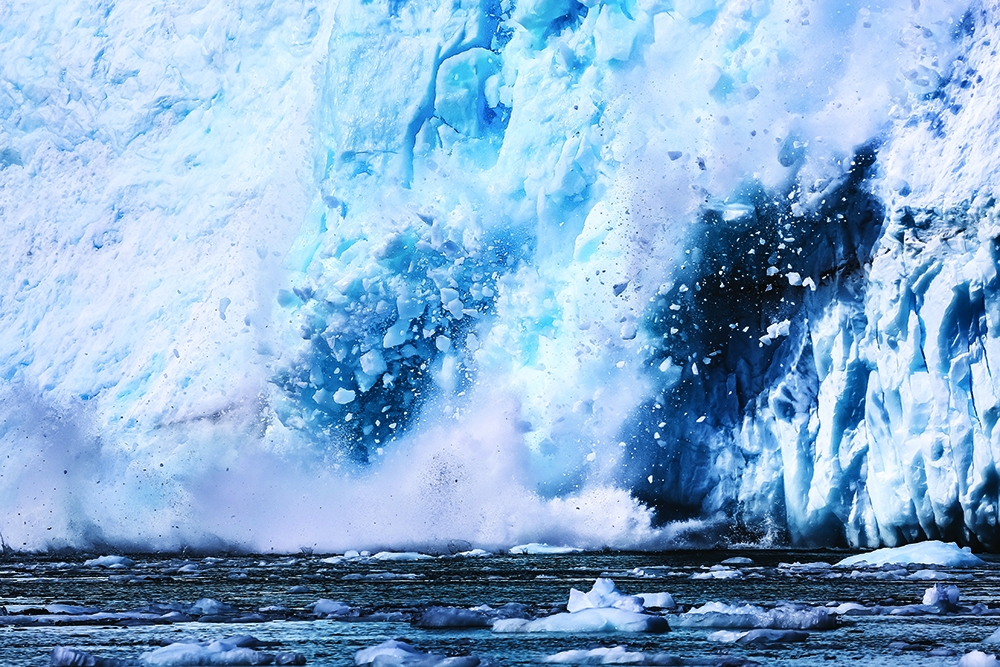

Right now, we’ve already seen a 1-degree increase, and there is already dangerous climate change for many people. The most obvious impacts are flooding, drought, and extreme weather, including precipitation and storm surge associated with hurricanes. These are cases where climate change works as a threat amplifier. But the evidence is becoming quite convincing that we have underestimated the effects of the warming itself, which we are already experiencing. We haven’t really been thinking about how the heat is accumulating and the impacts of that accumulated heat on melting ice. We are already committed to a pretty significant level of sea level rise, probably 10 meters over the next few centuries. And that’s a lot.

All this is almost certainly going to start to cause people to think about moving away from the coasts, and one of the places that will start to look inviting to them, potentially, is Michigan—in a sense, it’s a climate winner. The growing season, as you might call the time when we’re frost-free, has increased already. But on the other hand, the trend is also going to include more precipitation and more extreme weather events. That’s very certain.

How will climate change affect global food systems?

A professor of ecology, natural resources, and environment in the School for Environment and Sustainability, Ivette Perfecto, MS’82, PhD’89, studies sustainable agriculture, primarily in Latin America.

The effect that climate change has on agriculture can be devastating. Our present industrial agricultural system is very vulnerable to climate change because these are monocultures, with usually very reduced genetic diversity and very little protection of the soil. That sort of system is more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, especially drought or dramatic climatic events like hurricanes.

I work in the tropics, so I’m thinking primarily about what’s predicted to happen in the tropics, but I think that this applies as well to the temperate zone. Basically, most models predict that yields are going to go down in most places, mainly because there are going to be more prolonged droughts, more floods, and more dramatic weather. We will also see an increase in pest outbreaks as the range of many pest organisms expands.

The good news is that farmers are beginning to notice the effects of climate change and are already thinking about sustainability and how to develop more resilient systems. Small-scale farmers around the world are embracing this idea of “agro-ecological” systems, which are more diverse and protect the organic matter in the soil from erosion and runoff, helping it to retain more water. Plus, most of the carbon in terrestrial ecosystems is in the soil, so keeping that soil in place is important.

The good news is that farmers are beginning to notice the effects of climate change and are already thinking about sustainability and how to develop more resilient systems. Small-scale farmers around the world are embracing this idea of “agro-ecological” systems, which are more diverse and protect the organic matter in the soil from erosion and runoff, helping it to retain more water. Plus, most of the carbon in terrestrial ecosystems is in the soil, so keeping that soil in place is important.

Meanwhile, consumers will have to begin shifting their diets. A number of papers have come out recently about how our diets influence climate change—a diet with a fair amount of meat in it has a much stronger impact on greenhouse gas emissions than a vegetarian diet. The problem is that we have two trends. More people in the developed world are eating less meat, but as people get richer in countries like China, for example, more people are eating more meat. And what the outcome of that will be, I don’t know.

What if we could capture carbon dioxide before it gets to the atmosphere?

A professor of mechanical engineering, Volker Sick is director of U-M’s Global CO2 Initiative, a collaborative effort to produce economically sustainable products that would reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

We can definitely capture that carbon, but then what do we do with it? Some of it will have to be buried, but there are a lot of products that are—or that could be—made out of carbon dioxide, such as fibers, chemicals, fuels, or even food. There are companies working to create protein from carbon dioxide. There are ways we could make concrete without emitting so much carbon, in a way where you can lock it up as the concrete cures. A lot of these technologies are in their infancy, but some companies are ready to scale.

One of the things we’re working on at the Global CO2 Initiative is building this new industry in Michigan. We have a large manufacturing capability in this state, and here at U-M there are dozens of faculty working on this topic in many different disciplines. We also have an international team of experts that works with us to develop and deploy assessments—we need to know that any new technology is environmentally friendly and actually carbon negative.

It’s important, though, to note that there really is no silver bullet when it comes to climate change. It will require a lot of different expertise to survive it, and we’ll need to take into account local constraints and look at longer time frames—not just 50 years but 100 years, 1,000 years, or 10,000 years.

What questions remain for scientists and researchers?

A professor from practice at the Law School, Jennifer Haverkamp also serves as director of the Graham Sustainability Institute, which aims to translate research into real-world impact.

The main unanswered questions are: What are we going to do about it? What do we need to do to reduce emissions so that the problem is averted, to the extent possible? And, knowing that effects are already happening—and even with our best efforts, it’s going to get worse before it gets better—what can we do to prepare, to make this less painful and less costly for the world?

It’s important to point out that we aren’t just talking about the work of climate scientists. We’re talking about people across every discipline: law, economics, engineering, finance, medicine, the social sciences, behavioral science. There are many, many different ways to address the problem. It’s something for which just about everybody in academia could find a way to make a relevant contribution. University researchers still have particular persuasive powers, by being academics, and they need to make sure that the results of their research get into the hands of the people who need it, so that they can act on it.

Meanwhile, President Mark Schlissel has committed the University of Michigan to a pathway to carbon neutrality, and a lot of the value in that lies in sharing what we learn with other institutions and communities, to help scale up and transfer the solutions that we come up with. We’re one of many major research universities trying to figure out how to reduce our carbon footprint, and we are all laboratories for that effort.

Can a carbon pricing scheme, like a tax or cap and trade, actually work to mitigate climate change?

A professor of public policy at the Ford School of Public Policy, Barry Rabe studies energy politics and is the author of “Can We Price Carbon?” (MIT Press, 2018).

By definition, a carbon price steadily increases the price for use of fossil fuels, all of which are legal to produce, refine, and use across the United States. The primary challenges in the U.S. are political rather than technical. Still, North American and global experience suggests that carbon pricing (either carbon tax or cap and trade) is politically feasible. In Canada, a federal government devoted to carbon pricing reform recently won reelection. In the U.S., the regional approach holds great promise—in the Northeast, for example, where several states formed the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative to reduce electricity sector emissions.

The most likely scenario for future U.S. climate policy would likely be some combination of a carbon price with other regulatory or subsidy policy, ideally well-coordinated to reinforce each other. And that could indeed help put the U.S. on a path toward major greenhouse gas reductions over the next few decades. Any possible electoral transition after 2020 does not guarantee any particular climate policy, since executive-only action is very limited, and it’s unlikely to prove durable and effective over time. The challenge remains stitching together a coalition that would include some form of a carbon price and holding that together over time.

How can we ensure that people aren’t swayed by misinformation about climate change?

A professor of judgment and decision-making, Joe Árvai directs the Erb Institute for Global Sustainable Enterprise, a joint effort of the School for Environment and Sustainability and the Ross School of Business. His research focuses on how people process information and make choices.

In our research, we’re using interventions to get consumers of information on social media platforms to think in a deeper and more structured way about big, complicated problems. And we’ve found that it’s really about asking yourself some fundamental questions like, “Does the information I’m receiving seem politically motivated, too good to be true, too one-sided, too simplistic?”

When we can get people to roll through a series of questions like that as they consume information, it actually works really well. Then, you can get them to ask themselves an additional question, which is, “How important is it that the information I get encourages me to think deeply, to take different points of view?”

What’s great is that these questions work on misinformation, and they get people to trust it less and share it less with the different buttons they can push on Twitter or Facebook. But it doesn’t make them like, share, or trust real news about climate change any less. Research by a graduate student, Lauren Lutzke, ’15, MS’19, and I suggests that even a hardened climate skeptic can be influenced relatively easily and with measurable and meaningful effect.

Over 50% of Americans now get their news from Facebook, so what we need is fact-checking to be built into social media news feeds. And what would also be great is if, as you scroll through your news feed, you get a reminder every once in a while that encourages you to think a little bit more critically and a little bit more deeply.

EARTH DAY THEN AND NOW

Fifty years ago, a group of U-M students who called themselves ENACT (Environmental Action for Survival) put the University on the map nationally when they held a teach-in on the environment in March 1970 similar to the U-M teach-in on the Vietnam War in 1965. The four-day event was held in a packed Crisler Arena, with senators, ecologists, labor leaders, and corporate executives speaking out on how to save the Earth.

Five weeks later, the U-M teach-in became the prototype for the first Earth Day held on campuses across the country.

The University community has been celebrating Earth Day at 50 during the 2019-20 academic year to honor that environmental event as well as other milestones: U-M created the first forestry class in 1881, the first environmental justice program in 1999, and a campuswide sustainability institute in 2006.

A dedicated website, earthday.umich.edu, allows visitors to travel back in time to the 1970s and watch a 30-minute documentary on the teach-in. The video opens with footage of students smashing a car on the Diag to protest air pollution and goes on to cover the teach-in topics discussed that remain relevant to this day: overpopulation, the future of the Great Lakes, the root causes of the ecological crisis, and the effect of war on the environment.

An article posted on the site called “Agents of Change” highlights environmental leaders from the University who have played vital parts in the biggest environmental transformations of the past 40 years. And an events page informs visitors of the many environmental conferences, seminars, and symposiums happening on campus this winter and spring.

Perusing the “Historical Milestones” timeline on the site, one sees how the University’s commitment to the environment and sustainability dates back to the earliest decades on the Ann Arbor campus. In 1857, the youngest member of the faculty—a 24-year-old English professor named Andrew Dickson White—noticed a dearth of trees around the four existing academic buildings and began planting elms and evergreens. Over time, students assisted him. Today, as the timeline notes, that same dedication is evident in the students and faculty who regularly till a farm created in 2012 as part of U-M’s Sustainable Food Program at the Matthaei Botanical Gardens.

Finally, those interested in learning more about environmental issues can sign up for an online open course, including one about how to address and respond to the challenges of climate change.

For more information, check out the Twitter feed #A2EarthDay.

Amy Crawford is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Smithsonian, The Boston Globe, and Nature Conservancy magazine. Follow her on @amymcrawf.