U.S. Marine Amir Hekmati spent four years in an Iranian prison before earning a degree at UM-Flint. Here is his story of service, survival, and the congressman who was finally able to secure his freedom.

After years of imprisonment in a hostile nation, earning a college degree might be the least of a free man’s concerns.

But for Amir Hekmati, ’17, being able to hold a diploma was one of his “long-awaited goals.” In April, he fulfilled that dream when he received his bachelor’s degree in economics from UM-Flint. It was a goal that had taken a back seat for nearly six years to a far more insurmountable one: getting out of prison in Iran.

When the Iranian-American traveled to the country to visit family in the summer of 2011, he was no stranger to the Middle East. In August 2001, following his graduation from high school and one month before the Sept. 11 attacks, Hekmati enlisted in the Marines. Soon after, he was shipped to Iraq, where his Arabic proved valuable.

“I was constantly engaged in everything from combat operations to negotiations with Iraqi politicians,” Hekmati said. (Citing an ongoing lawsuit with Iran over his captivity, Hekmati would comment for this article only via email and through Mitchell Rivard, U.S. Rep. Dan Kildee’s deputy chief of staff.)

After completing his military service in 2005, Hekmati worked on a language-learning app for the Department of Defense. He also earned an associate’s degree in Arabic from the Defense Language Institute, studied international business through the University of Phoenix, and took classes at Monterey Peninsula College. He was about to start as a full-time student at U-M when he was seized in August 2011 in Tehran by Iranian authorities, who accused him of being an American spy.

“Mr. Hekmati was arrested and imprisoned by Iranian officials without warning as he was getting ready to attend a family holiday celebration,” Hekmati’s attorney, Emily Grim, wrote in a May 2016 lawsuit filed against Iran. “When Mr. Hekmati did not arrive at the party, members of his family in Iran went to the cousin’s apartment where Mr. Hekmati had been staying. His phone, computer, camera, and passport were missing. It was clear that the apartment had been broken into and that a struggle had taken place.”

The lawsuit accuses the Islamic Republic of torture and describes, in harrowing detail, the conditions Hekmati says he faced while in prison. Iranian authorities allegedly whipped him, forced him into stress positions, kept him from sleeping, and stunned him with a Taser. The goal was to prompt a “confession” that he was spying on Iran for the CIA. Eventually, they got one on tape, which Hekmati says was coerced.

Declared “corrupt on Earth” and an “enemy of God,” Hekmati was sentenced to death in January 2012. “I remember being in the sort of death row area, where there were prisoners being taken to be executed, and I would hear them screaming and crying,” Hekmati told the Rotary Club of Flint in a May 2016 speech, as reported by MLive. “All I had was my faith, prayer, and the role models and experiences I had as a Marine.”

Iran’s Supreme Court overturned the death sentence two months later in a retrial without Hekmati present. He would not find out he had been resentenced to a 10-year prison term until two years later.

Hekmati was one of several American citizens held in Iran during this time; they included The Washington Post’s Tehran correspondent, Jason Rezaian. It would take a sizeable U.S. political intervention to bring them home.

“Right after I took office (in 2013), my staff and I started digging into it and connected with the family,” said Kildee, whose Michigan congressional district includes Hekmati’s hometown of Flint. “We made a decision that we were going to take this on and we were going to get him out of there.”

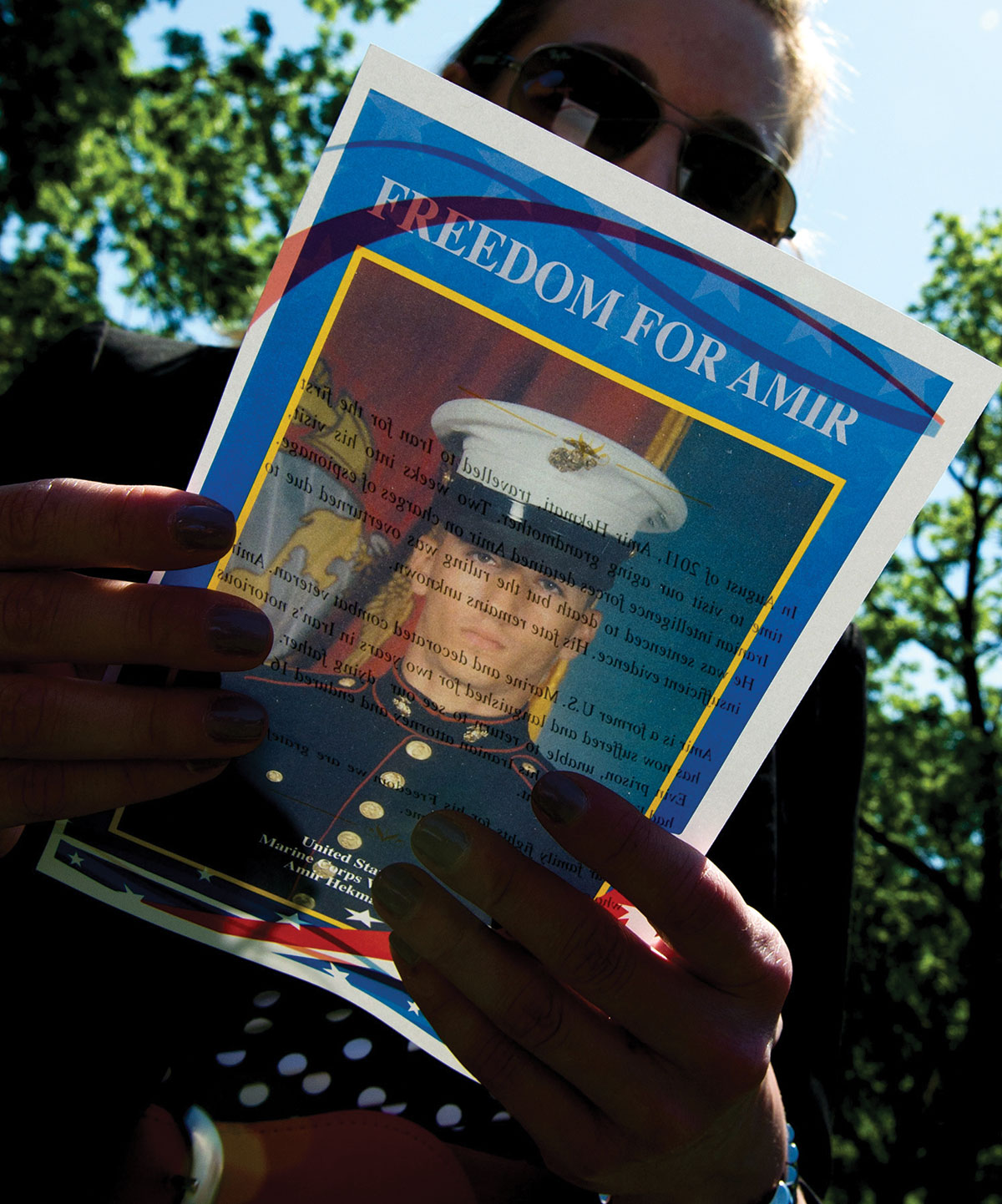

Kildee helped Hekmati’s family launch a public awareness campaign to raise the profile of his captivity. The Free Amir campaign spread across social media as Kildee authored a resolution calling for his release, which every member of the House of Representatives ended up signing. President Barack Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry also repeatedly called on Iran to release Hekmati and the other American prisoners.

Because the U.S and Iran have no formal diplomatic relations, efforts to release Hekmati had to be conducted through third parties, including Swiss diplomats. But there was also the occasional face-to-face encounter. For example, at the United Nations General Assembly meeting in 2015, Kildee—invited by Samantha Power, then the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations—met with Iran’s Foreign Minister Javad Zarif to discuss Hekmati’s case.

Finally, in January 2016, Hekmati and three other U.S. prisoners were released in a prisoner swap that included giving clemency to seven Iranians being held in the U.S. for sanctions violations. Around the same time, the U.S., U.K., Russia, France, China, Germany, and EU all brokered a deal to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon. The proximity of the two events led many to speculate the prisoners had been held for political leverage.

Once it was clear that the plane carrying Hekmati had left Iranian airspace, his family and Kildee traveled to the U.S. military hospital in Germany where he was being treated.

“I still remember what I said to him when I walked over, put my arms around him and gave him a big hug,” Kildee recalled. “I just said, ‘Wow. You’re Amir Hekmati.’”

One month later, Hekmati embraced his family on the tarmac of the Flint International Airport.

“I’m standing here healthy, tall, and with my head held high,” Hekmati told reporters from the tarmac. “I’m glad to be here, and I appreciate everyone’s support.”

Hekmati wouldn’t have to wait long to return to his studies. UM-Flint Chancellor Susan Borrego said she texted Kildee as soon as he had stepped off the plane. Borrego had one message for the newly freed Hekmati: “If he was interested in completing a degree, we would help him find the resources to do that.”

Hekmati didn’t talk much about his years in captivity while at U-M, and Borrego never asked him to speak on campus about his time in Iran. “You want students to be able to pursue their degrees for their reason. Amir is very bright and very competent. He managed his academic program on his own.”

Hekmati declined to discuss his plans for the future, but said holding a U-M degree after living through such an experience feels momentous. “Starting over after a very difficult 4 1/2 years has not been easy. I’m very thankful to the faculty at U-M.”

For Kildee, the timing of Hekmati’s return felt particularly significant. Hekmati arrived home mere weeks after Flint had declared a state of emergency over its lead-contaminated water supply.

“For a city that was struggling and wondering whether or not there was any reason for hope for the whole community, to have tangible evidence of the power of hope in one person was pretty remarkable,” he said. “Amir came home.”

Andrew Lapin, ’11, is a freelance journalist based in Chicago. His writing has appeared in NPR, The New York Times, National Geographic, and more than a dozen other publications. He was the editor-in-chief of The Michigan Daily in the summer of 2010.