In spring 2020, after Michigan residents entered lockdown and the state’s schools closed to prevent the spread of coronavirus, Karen noticed her 15-year-old son, James, started spending more time on his smartphone and began eating more junk food.

“During the lockdown, James would eat mindlessly while he was busy on his phone,” Karen says. “He’d grab a big bag of chips, and before long the whole package would be gone. If he ate a box of cookies, the sugar would give him a little high and make him feel good. Then he’d be too full to eat a regular healthy meal. I definitely saw an increase in his phone use and junk food eating during the early days of the pandemic.”

A few years earlier, James had struggled with depression, anxiety, and videogame addiction. The social isolation brought about by COVID-19 may have exacerbated his underlying stresses.

“I think James was a little depressed because he couldn’t see his friends,” Karen says. “When kids are socially anxious, it’s easier for them to bury themselves in their phones and eat junk food.”

Over the past decade, American teenagers have become avid consumers of social media, videogames, and entertainment on their smartphones. The onset of the coronavirus pandemic pushed them even deeper into the digital world, sharply escalating their dependence on these omnipresent mobile devices.

Yet the link between excessive smartphone usage and U.S. adolescents’ relationship with food has been largely unknown. Until now.

A new U-M study reveals that teenagers who have highly addictive patterns of smartphone use are more likely to show addictive and disordered eating behaviors. Furthermore, the researchers say, adolescents who experience difficulties controlling their emotions are more apt to struggle with problematic smartphone use and compulsive food consumption.

If a teen is showing addictive patterns of using his or her smartphone, it is important to look for signs of problematic eating.

“Teens are at especially high risk for addictive behaviors, because they are going through many emotional changes, and the brain regions that respond to reward are at a peak during this time,” says psychology professor Ashley Gearhardt, ’03, who led the research study. “Both smartphones and junk food tap into the reward system in unnaturally intense ways. Right now, teens and their parents are simultaneously trying to figure out how to navigate a novel, highly rewarding technology and food environment.”

Sarah Domoff, a research faculty affiliate in the School of Public Health who co-authored the study, says the coronavirus pandemic has placed additional stress on teens by disrupting their school schedules, limiting their social activities and in-person interactions with peers, and curtailing their normal channels for coping and support.

“Adolescents who have problems dealing with their feelings are more likely to turn to their smartphones to escape or to relieve negative emotions,” says Domoff, who studies the potential impact of mobile technology use on child health and development. “This study demonstrates that addictive smartphone use is associated with disordered eating, including loss of control over junk food consumption.”

A Tsunami of Smartphones

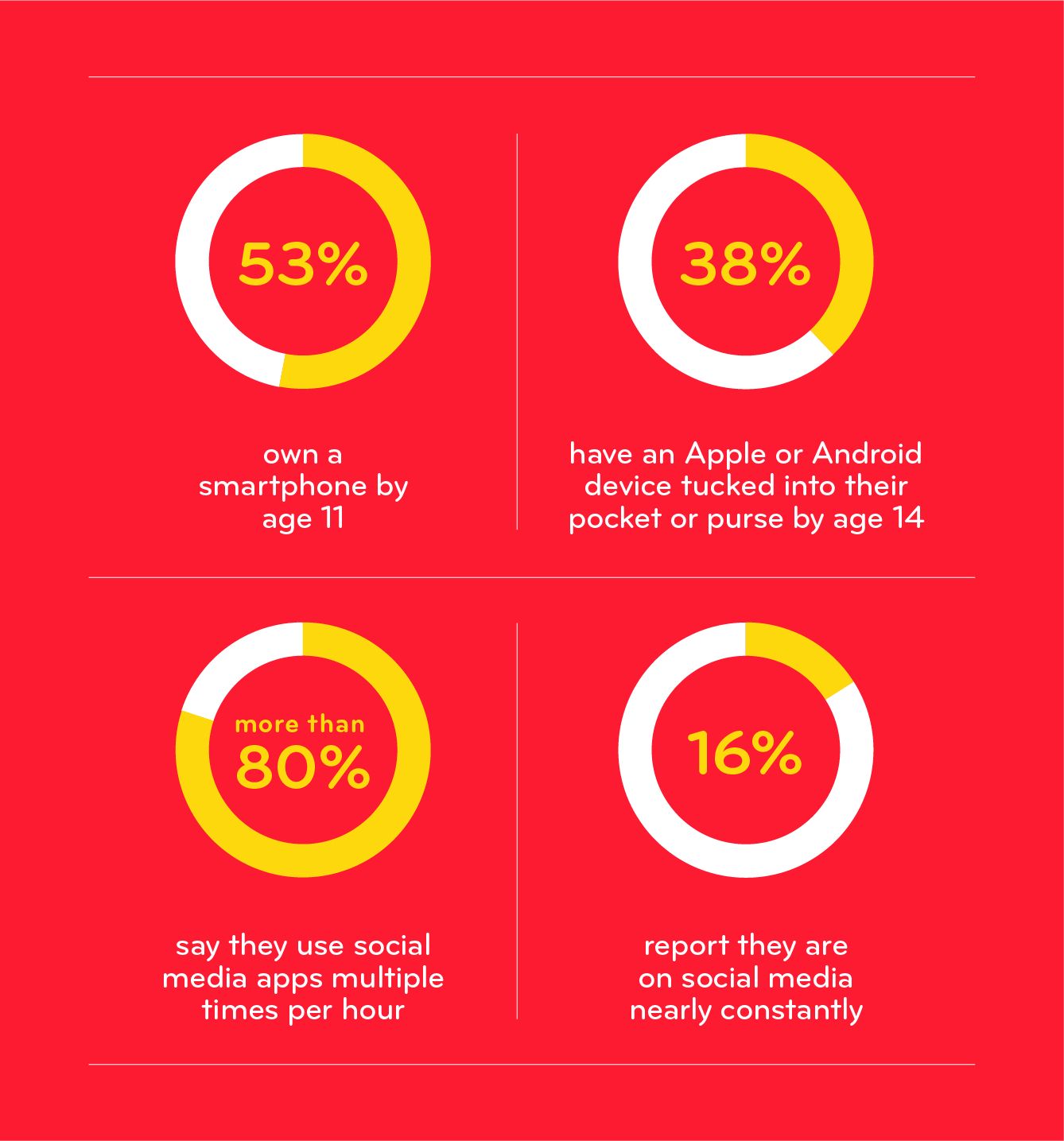

Smartphone access and ownership have continued to rise, sweeping over America’s adolescent population, despite research linking excessive phone use to sleep disruption, depression, anxiety, and poor academic outcomes. Following are some of the disturbing numbers about U.S. teens, according to Common Sense Media.

In addition, nearly half of American parents admit they are concerned about their adolescents’ addiction to mobile devices, Common Sense Media researchers report.

In an April 2020 survey, advocacy group ParentsTogether found that American children now spend an average of nearly six hours a day online, a 50% increase over pre-pandemic use. Half of those youngsters rack up screen time exceeding six hours daily, a 500% spike in usage from pre-COVID-19 times.

Emma Sutherland, ’17, MPH’20, who joined the U-M research team while she was an undergraduate student, has observed the surge in teenage smartphone use firsthand.

“My generation started growing up with cellphones,” says Sutherland, who was a high school sophomore when she got her first phone. “Now kids want smartphones in third, fourth, and fifth grades. This is a new and novel phenomenon, so it was important for us to establish baseline knowledge that other researchers can build on.”

The U-M research team approached its study with several objectives.

First, they examined how differences in gender, race, ethnicity, and parental education affect addictive phone use. Second, they investigated whether adolescents who report greater addictive phone use also are severely or morbidly overweight and have greater emotion-regulation difficulties, dysregulated or restrained eating, and food addiction. Finally, they explored whether emotion-control difficulties play a role in the association between compulsive phone use and problematic eating behaviors that increase obesity risk.

“Connecting with Dr. Domoff allowed us to take what we have learned at the FAST lab about how junk food may be triggering addictive process-es and apply it to smartphones,” explains Gearhardt, who has studied junk-food addiction and withdrawal in adults. She directs the Food and Addiction Science and Treatment (FAST) lab within LSA.

Initially, the researchers surveyed a group of teens about the extent of their smartphone use, their perceptions of personal difficulties in regulating emotions, and their eating behaviors. The participants were measured to calculate their body mass index percentile and percentage of body fat, and underwent functional MRIs, which measure brain activity.

As part of the assessment, the team administered the Addictive Patterns of Use scale, which gauges excessive smartphone usage. Indicators of addiction and dysfunction include tolerance (needing to use a phone for longer periods of time), withdrawal (feeling irritable when unable to access or use a phone), use of a phone to manage moods and feelings, and psychosocial impairment due to use.

The researchers also examined how the teens engaged with others via social media and consumed targeted ad content and messaging on their smartphones. Equally important, the study focused on excessive phone use that impairs daily life and normal activities rather than on the total number of hours spent online.

“Mobile media enable adolescents to view and interact constantly with highly curated images and advertisements,” explains Domoff, noting that teens often compare themselves to the idealized body shapes and sizes they see on Instagram and Facebook. “We wanted to consider whether excessive exposure to these images and internalization of these messages would be associated with maladaptive eating behaviors or dysregulated emotions.”

The study provided preliminary evidence demonstrating that disordered eating is linked with addictive smartphone use among U.S. adolescents.

“Heavy phone users were more likely to report eating in response to their emotions and trying to restrict their food intake,” Domoff says. “They also had a higher percent body fat and were prone to eat highly processed, sugary, and fatty foods in an addictive way.”

Differences between the sexes also emerged. Girls showed significantly higher levels of addictive phone use, which also was associated with greater levels of disordered eating and food addiction than their male counterparts. The researchers attributed these gender differences to the social features of several popular smartphone apps, the higher use of social media by girls, and the salience of peer relationships in girls during adolescence.

In addition, the study revealed that teenagers who used their smartphones excessively also reported having greater trouble dealing with their own feelings and moods.

“Difficulties regulating emotions effectively is a potential pathway that may be linking these problematic behaviors,” Gearhardt says. “So if a teen is showing addictive patterns of using his or her smartphone, it is important to look for signs of problematic eating.”

The researchers found no significant impact of race, ethnicity, or parent-education level on the study results.

Methodology

The two-year research project involved 111 adolescents living in south-central Michigan and was conducted at the U-M Food and Addiction Science and Treatment (FAST) lab from July 2015 to August 2017.

The participants included 49 boys (44%) and 62 girls (56%).

Of those, 79 identified themselves as white, 19 as Black, nine as Hispanic, and 13 as biracial or other.

The group’s median age was 14.5 years.

Both teenagers and their parents have an important role to play in promoting healthier patterns of adolescent phone usage and eating behavior, the researchers say.

“Developing an unhealthy relationship with junk food as a teen can set up eating habits that last a lifetime and open the way for obesity and diet-related diseases like diabetes,” Gearhardt says. “The food industry knows teens are primed to want their products, so they aggressively market unhealthy ones to this highly receptive audience.”

The food industry knows teens are primed to want their products, so they aggressively market unhealthy ones to this highly receptive audience.

Teens are at higher risk for developing addictive behaviors than younger children and adults because their reward system becomes stronger at this age, but their ability to inhibit compulsive impulses doesn’t mature until early adulthood. Furthermore, parents don’t have as much control over their children’s eating habits during adolescence.

“Combine all this with teens’ intense emotions and raging hormones, and it really is the perfect storm!” Gearhardt says. “This can be a high-risk time that parents should pay attention to.” She also recommends teenagers seek in-person social support, engage in activities that aren’t online, learn to meditate, and start journaling their daily experiences.

“Helping teens identify their emotions and develop healthier ways to cope with their feelings may be important in helping them reduce both addictive smartphone use and food intake,” Gearhardt says. “Increasing emotion-regulation skills has been shown to have important benefits across the lifespan.”

Domoff, who counsels parents and teens in her clinical psychology practice, offers several strategies for avoiding or reducing addictive smartphone use.

“As parents, it is important to have a conversation with your teenagers (preferably before they get their own smartphones) about healthy use, risks, and how they (and you) will know if their phone usage becomes problematic,” Domoff says. Some families write and sign formal smartphone agreements or set up family media plans.

Parents also can help their children by modeling healthy, adaptive phone-use behaviors.

“Teens learn from the people around them,” Domoff explains. “Parents need to show they are impacted by screens in both good and bad ways, but also demonstrate they are able to set boundaries and resolve problems with phone use.”

Keeping smartphones out of the bedroom and restricting online activity before bedtime will pay off in several ways, she says.

“Past research has shown that phone use disrupts adolescents’ sleep, and now we’re seeing links between phone use and emotional problems,” Domoff says. “Sleep is important for both mental and physical health, and phones are disruptive in both domains.”

Finally, she recommends that parents and teens work together to promote healthy engagement and interactions on social media while discouraging passive scrolling and making hurtful comparisons to others.

“Parents need to know what their teenagers are viewing online and to discuss which content is uplifting and positive versus problematic and disruptive,” Domoff says. “Teens have better outcomes when they use social media to build relationships, get support, and provide encouragement to others.”

The U-M study set the foundation for future research on the effects of addictive smartphone use and disordered eating. However, the researchers say, long-term studies with larger, more diverse groups of teens are needed, because some adverse health outcomes such as obesity may not emerge until late adolescence or early adulthood.

“The more we know,” Gearhardt says, “the more we can design interventions and policies that reduce patterns of compulsive and problematic smartphone use.”

Claudia Capos, ’73, an award-winning journalist, is the owner of Capos & Associates, a communications company. Her articles on research, business, celebrities, and travel have appeared in national and international publications.