A Seat at the Table

•

When the NCAA began allowing student-athletes to make money from their name, image, and likeness (NIL) in July 2021, Kendall Murray didn’t think the change would mean much to her.

The University of Michigan volleyball player from Ann Arbor assumed that only athletes in sports like football and men’s basketball would see any real money. After all, the athletes that are the focus of highlight shows on TV were probably the only ones with real commercial appeal. But that quickly changed after Murray’s mother encouraged her to look into the issue deeper and she found there were a multitude of ways to make money that didn’t involve advertising deals with big brands.

“I’ve been able to benefit from it a lot,” says Murray, who just finished her junior year at U-M. “I have to put myself out there a little bit more than a star basketball player does, but if you really sit down and put in the work and figure out the focus that you want to do, I think anyone can benefit from it.”

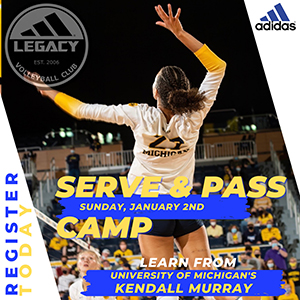

For Murray, that focus has been volleyball clinics for middle and high school students. She holds two-hour sessions with a local club, charging each student $60.

“I’ve been able to do that a lot and that’s been a big source of revenue for me personally. That’s something I didn’t even think about before NIL,” Murray says. “And it’s not just something that I do, but my teammates do as well.”

Murray has also done social media deals with two Ann Arbor businesses: Blue Lion Fitness and Restore Hyper Wellness.

Just two years ago, the clinics and partnerships would have violated NCAA rules. For decades, the governing body for college athletics barred student-athletes from making marketing agreements or using their status as college athletes to make money. But in 2019, state lawmakers began to pass new NIL laws for college athletes that attempted to force the NCAA’s hand on the issue. By June 2021, the NCAA relented and lifted its NIL restrictions.

The measure means student-athletes can be paid to endorse products, hold camps, sell merchandise, hold autograph signing sessions, or receive appearance fees at events. The NCAA still bars students from simply being paid for no work or as part of a recruiting inducement.

And while the majority of the reported large deals have gone to high-profile male athletes in football and basketball, Murray is among the growing number of female and Olympic sport athletes to benefit from the new rules.

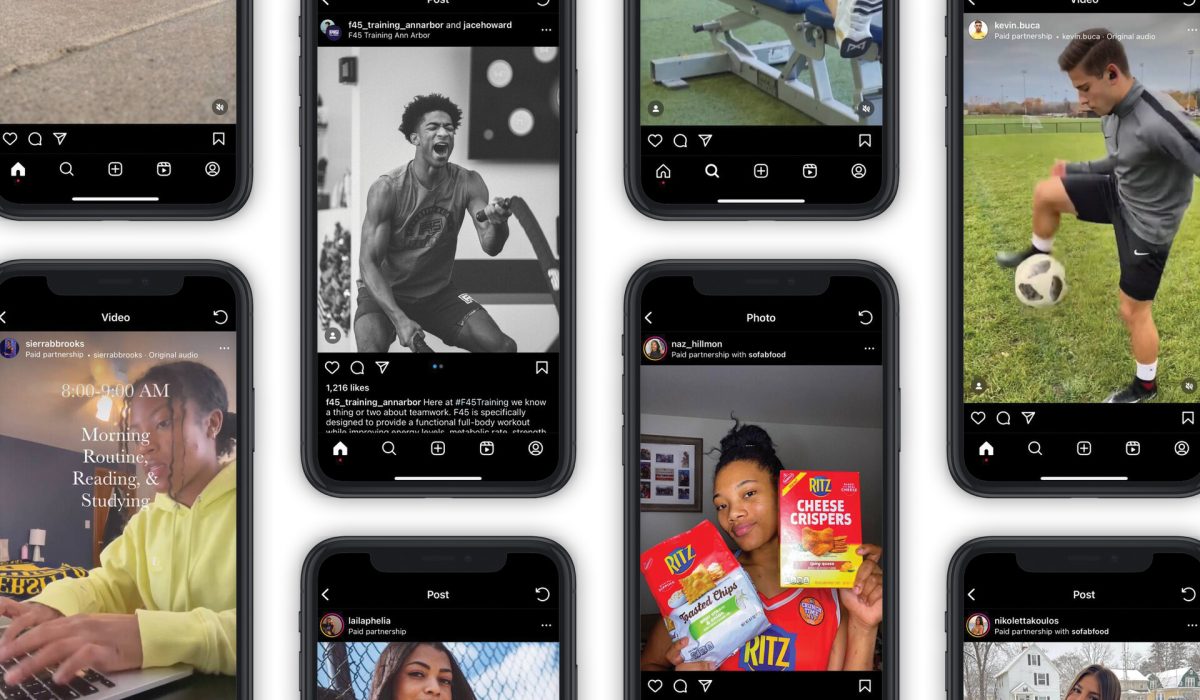

While scanning the social media accounts of U-M athletes, it’s not hard to find paid partnerships. Among them, women’s basketball player Cameron Williams goes shopping for her apartment at retailer Lowe’s, gymnast Sierra Brooks walks viewers through a day in her life as a student-athlete and how she fuels her body with milk, and golfer Mikaela Schulz shows how she “hits bombs” with FlightPath tees.

Wrestler Cameron Amine received some Barstool-branded merchandise for agreeing to be a “Barstool athlete,” Bubbl’r energy drink sent him product in exchange for a social media endorsement, and Focus Financial, a local vestment adviser firm, paid him a few thousand dollars for some Instagram posts.

“It’s definitely worth it,” Amine says. “ … With the money, it makes my life a little bit less stressful having spending money instead of having to live paycheck to paycheck if you’re on a scholarship.”

Everyone Eats

The financial arrangements of NIL deals are private unless a student-athlete chooses to disclose them, so it is unclear exactly how many deals have involved U-M athletes.

“NIL has taken a path that might be familiar to folks who are involved in anything new, anything emerging, and that is an initial launch followed by great uncertainty, lots of questions, trial, error, internal conversations, agreements, and disagreements,” U-M Athletics spokesman Kurt Svoboda says. “All of this is with an eye towards supporting our student-athletes and being supportive of their rights to be able to capitalize.”

To help student-athletes navigate things such as trademark rules and tax implications, Svodoba says the University is organizing a variety of workshops and making legal experts available to help mitigate the risks.

“I refer back to why we’re all here, and that is to work with our student-athletes, to help educate them and help them understand what they can and can’t do and what the reasons for it are,” he says.

“If you look at it like a dinner table, we all sit at the table. We might not get the same portions, but we’re participating. That’s the key.”

--Jamie Morris, X’87

The athletes are free to make their own deals but can also work with NIL collectives which aim to secure partnerships on their behalf. Jamie Morris, X’87, a former standout running back for the Wolverines, started the nonprofit Stadium and Main last year. One of a small number of NIL collectives working with U-M students, the group aims to benefit athletes in all sports.

“If you look at it like a dinner table, we all sit at the table. We might not get the same portions, but we’re participating. That’s the key,” Morris says about the gulf between football and basketball NIL deals versus other sports.

He says Stadium and Main primarily organizes team-oriented community service events where the athletes receive a small appearance fee. Since 2022, the collective has worked with about 75 student-athletes including those from women’s soccer, volleyball, cheerleading, and field hockey.

“The good thing is you don’t have to have a commercial or anything like that to participate,” Morris says. “You can go out and do community relations — go read books to young kids, go to the Mott Children’s Hospital. It’s a great opportunity for the students to learn about themselves, and who they are.”

Best Fans In The World!! Can’t wait to run it back with my brothers!! Shout out to @valiantuofm & https://t.co/06k3UF1joU for helping me keep my guys!! Go Blue〽️ https://t.co/T0cw8G2bRP

— #2⃣BeSavage (@blake_corum) January 15, 2023

Staying One More Year

Of course, many of the headline-making NIL deals involve high-profile football players. Several of the team’s biggest stars decided against declaring for the NFL draft and will remain on campus. Without the ability to earn a significant income in college, the move was something potentially unthinkable just years ago.

After running back Blake Corum, left guard Trevor Keegan, and right guard Zak Zinter announced they were staying, Corum took to Twitter to give a “shout out to . . . onemoreyearfund.com for helping me keep my guys.”

The tweet was an almost explicit acknowledgment that the three players, along with wide receiver Cornelius Johnson and linebacker Michael Barrett, were staying put because Wolverine donors had formed One More Year, an NIL collective aimed at retaining key U-M football players.

“Blake could [have left] this year and [been] a late first-round or second-round draft pick, and make millions of dollars, but he’s earning at a pretty high level from NIL and doesn’t see the immediate financial need to do that,” says Jared Wangler, ’18, owner of Valiant Management, the Ann Arbor athlete management firm that launched the One More Year fund. “He wants to come back and improve his draft stock, get more involved with the community, get his degree, establish his legacy here. Before NIL, it may not have been an easy decision for him because he would have had to weigh the pros and cons of not securing a financial opportunity like going to the NFL.”

Corum is one of several student-athletes to give back to the community with some of his NIL funds. For the past two Thanksgivings, he’s donated hundreds of turkeys and other fixings for those in need in Superior Township and Ypsilanti, Michigan.

Lifting All Sports

Where NIL really shines, Morris says, is with athletes that will never make money playing the sport they love. The star football players will likely go on to lucrative professional careers, but they are the outliers.

“Only 2 percent [of college athletes] will go pro. The others, they are at the height of their game and their popularity here in college,” Morris says. “So, this is the time to take advantage of that. That’s what we’re trying to promote for them.”

For her part, Murray says she has mixed feelings about how well U-M is helping its athletes, saying more could be done to educate students on the process or even access to lawyers.

“I have full faith that we can be one of the best NIL schools,” Murray says. “It’s going to be a factor in where people go to school. When I was being recruited, I wasn’t thinking about, ‘How do you help your athletes with NIL?’ That wasn’t a question, but now it’s going to be a question.”

Morris agrees, saying that’s why he believes it is so critical to get athletes from every sport to benefit from NIL.

“I don’t want just the best football team,” he says. “I don’t want the best basketball team. I want the hockey team to win, but I don’t want just the best hockey team. I want the best damn athletic department in the country.”

JEREMY CARROLL is the content strategist for the Alumni Association of the University of Michigan. STEVE FRIESS is a Michigan-based freelance writer.