Five decades ago, U-M’s College of LSA launched the Residential College, an innovative social and academic experiment. Today, the small liberal arts community continues its mission: to give students an active voice in shaping a unique learning experience.

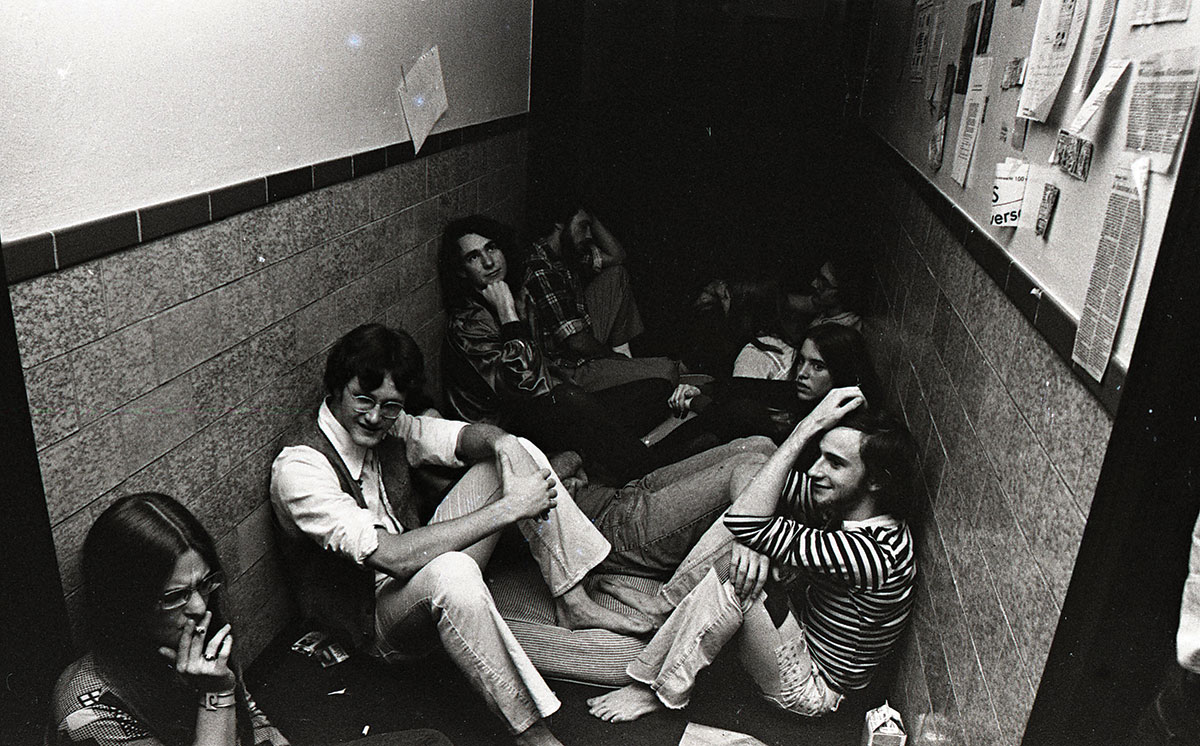

On any given day during the last 50 years, the scene at the Residential College (commonly known as “the RC”) would not have been very different from today. In 1967, students debated the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. In 2017, the topics are social justice and climate change. Pajama-clad undergraduates roll from bed to classroom and roam the halls of East Quadrangle, still eager to participate in the RC’s core curriculum, much of which remains the same. Students still must complete a first-year seminar, pass a foreign language proficiency exam, and take an arts practicum. (Hence, the continuous sounds of music, dance, and dramatic readings emanating from behind closed doors.)

Before the RC opened, more than a decade of planning went into the formation of the four-year, interdisciplinary liberal arts program, which is unique to campus with its own curriculum and academic advisers. (The planners also hoped for its own building, but instead it occupies 60 percent of East Quad.)

Its purpose was to combine the advantages of a small college with the resources of a large research university. It also had a second mission: to give students an equal voice with faculty by creating a living-learning environment that would promote constant interaction and mentoring.

“We succeeded. The whole thing is built on enthusiasm,” says Carl Cohen, the recently retired philosophy professor who joined the RC when it opened and also served on the planning committee. “As faculty, we were always around in friendly garb and friendly spirit. To this day, it remains a happy place of harmonious relationships.”

Alexander Kime, ’17, agrees. “The RC is a powerful experience. To see the same people in class, in the dining hall, and on your floor upstairs in friends’ rooms fosters a huge sense of belonging, as does having one-on-one tutorials with professors and classes of just five students.”

Over the years, the college has continuously lured a certain type of student, despite there being no entry requirements, other than admittance to U-M. “The RC attracts the most motivated and committed students and the most lost and at-sea students,” says Charlie Bright, a history professor emeritus who taught at the RC for 40 years, including two stints as its director. “That is not a bad combination. They challenge each other in interesting ways.”

Robin Wolfson, ’83, says the RC changed her life. “The interdisciplinary classes connected all my varying interests, from science to literature.” She recalls, in particular, an RC project that combined her interests in anthropology, research, and the music of the Grateful Dead. It was titled “What it means to be a Dead Head,” and her professor loved it.

Jonathan Wells, PhD’98, the current RC director, now faces a generational transition with the loss of Bright and Cohen, as well as other senior instructors. Still, he feels optimistic—and not just because he has two Pulitzer Prize-winning professors on his faculty. He is planning to expand the global reach of the curriculum, which has focused during the last half century primarily on Western civilization. He recently hired a lecturer in Islamic studies and is considering adding Arabic to the language roster.

Wells is also proud that the 2017 cohort of RC freshmen is the most diverse to date. “The fundamental DNA of the RC is to be committed to social justice, racial and gender equality, and the LGBT community,” Wells says. “We respond to the progressive impulse of our students and have done that since the RC was born in the midst of the counterculture movement. We are, and will continue to be, a welcoming institution.”

1966: THE REPORT OUTLINING THE PLAN FOR THE RC WAS KNOWN AS THE “BLUE BOOK.”

In “A Short History of the Residential College at the University of Michigan,” written by Professor Emeritus Charlie Bright and RC faculty member Michelle McClellan, the authors explain the college’s simple message: “To enable students to find their voice in whatever idiom or medium and to practice their speech in whatever language, whether in writing or movement, performance or practice, reflection or action, orally or signed.”

1967: THE RC OPENED ITS DOORS TO 217 FIRST-YEAR STUDENTS, HOUSED IN EAST QUAD.

The original plan was to move the RC into an $11 million, dedicated building to be built on North Campus by 1969. But the funding never materialized. In 1968, the entire RC student body met with the board of regents to ask if they could stay in East Quad permanently. In the end, $2.5 million was allocated to reconfigure the residence hall with classrooms, faculty offices, studios, and performance spaces.

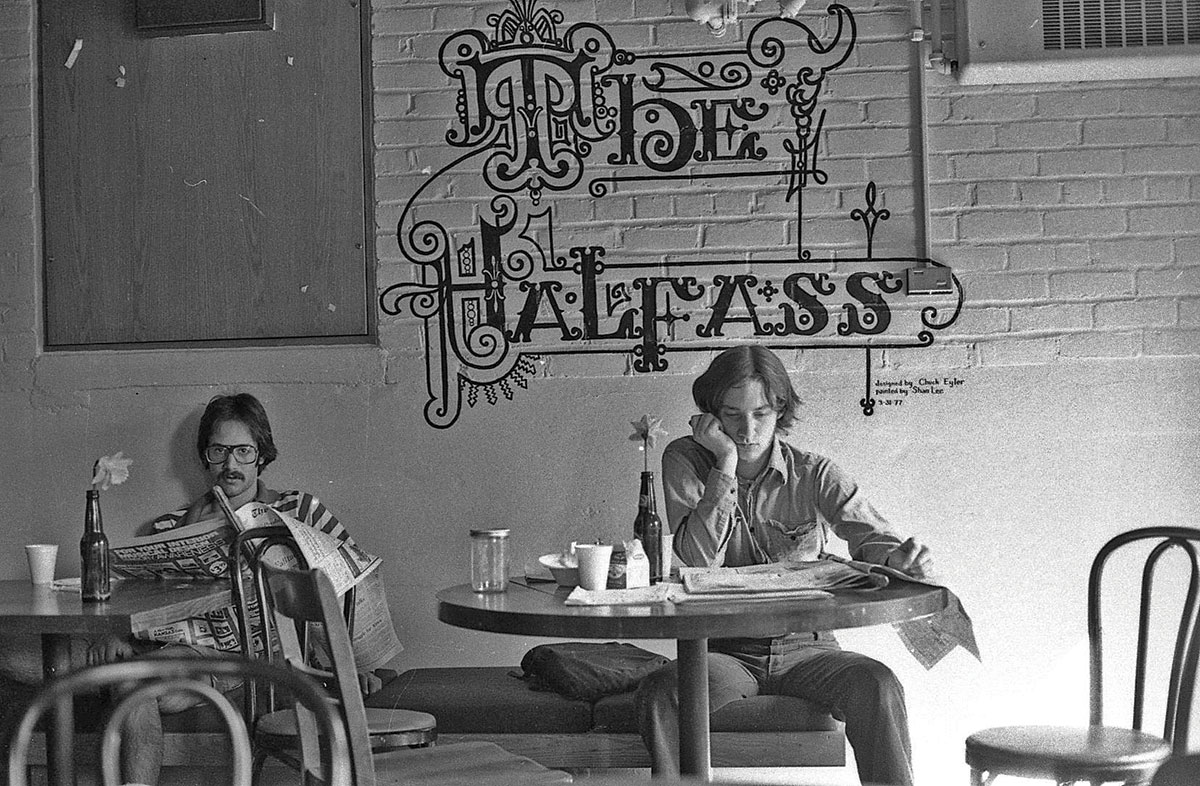

1969: THE RC’S GOVERNING BODY—THE REPRESENTATIVE ASSEMBLY, DUBBED THE “REP ASS”—QUICKLY BECAME A HUB OF STUDENT ACTIVITY, DEBATING EVERYTHING FROM NATIONAL POLITICS TO THE RC’S CURFEW HOURS AND THE STUDENT-PERCEIVED RIGIDITY OF THE ACADEMIC PROGRAM.

In 1970, many of the core curriculum requirements were changed, including the four-year residence rule. To graduate from the RC, current students must live in East Quad for the first two years, although some stay on longer to work as resident and peer advisers.

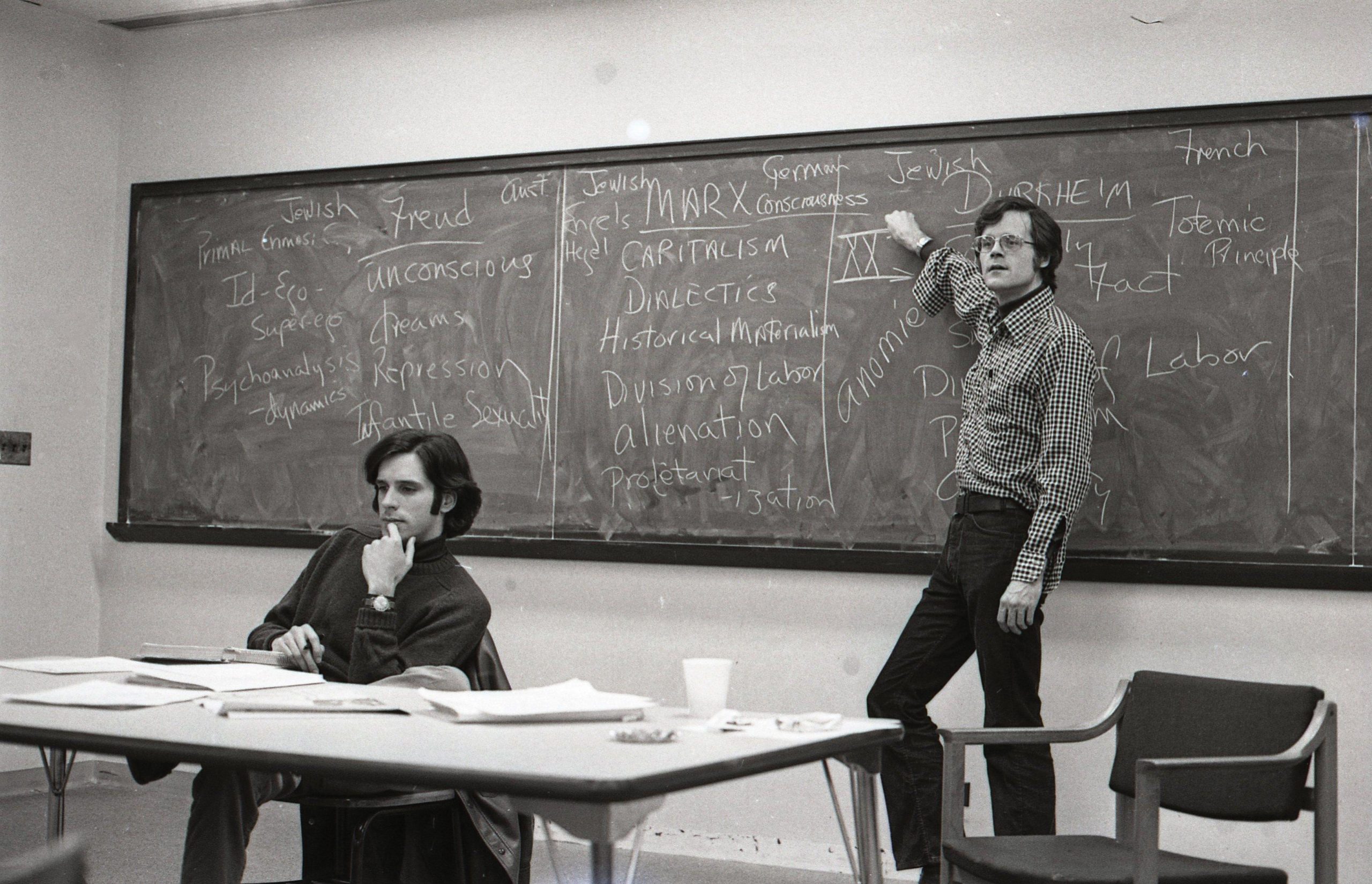

1971: DISAPPOINTED BY THE DISMANTLING OF PARTS OF THE CORE CURRICULUM AND PERCEIVED STUDENT INSUBORDINATION, HALF OF THE ORIGINAL LSA FACULTY WHO TAUGHT AT THE RC BOWED OUT.

The dean of LSA formed a faculty committee to assess whether the RC should continue. It survived with the recommendation that they build interdisciplinary majors that are different from those offered in LSA. Today, the RC offers five majors: arts and ideas in the humanities, social theory and practice, drama, creative writing and literature, and an individualized concentration.

1980: AN ASSESSMENT REPORT MADE COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT A PRIORITY.

It read, “a proper field study program should not only get students OUT of the quad; it should also bring the problems and practical dilemmas of the larger community INTO the college.” Those words encouraged the creation of more community-focused programs, such as the current Freedom House project, where advanced French students tutor refugees from French-speaking West Africa and assist in transcribing legal documents.

1985: HEADING OFF A STAFFING CRISIS, THE BOARD OF REGENTS APPROVED A THREE-YEAR, RENEWABLE CONTRACT FOR RC LECTURERS.

With only a small number of full-time and part-time LSA faculty funded to work at the college, RC lecturers were often creative artists with no tenure tracks, leading to high turnover.

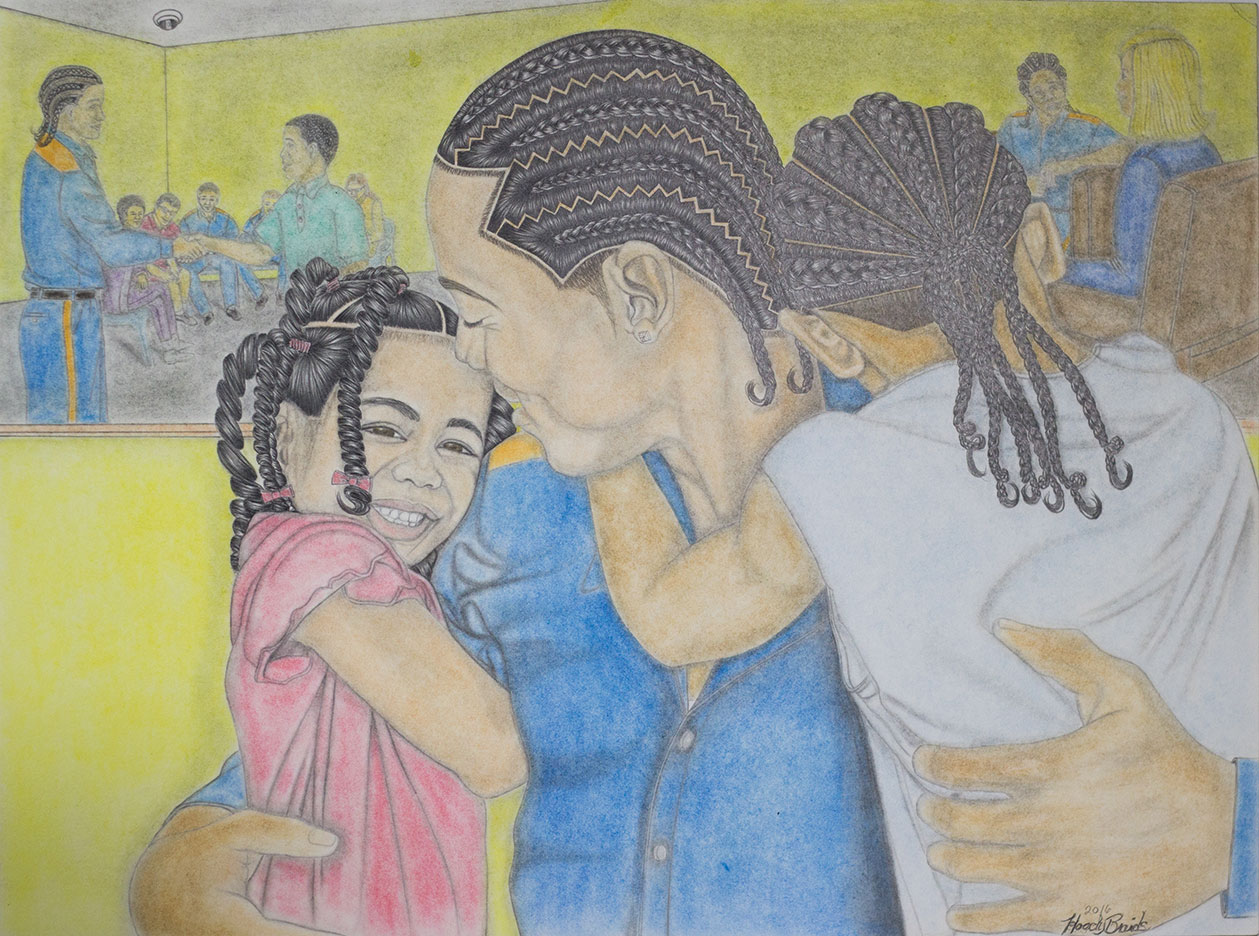

1990: FROM A SINGLE THEATER WORKSHOP IN A CRIME AND JUSTICE COURSE, THE PRISON CREATIVE ARTS PROJECT LAUNCHED.

Through this long-running program, students work on visual and performing arts projects with men and women in Michigan prisons.

2001: SHAKESPEARE IN THE ARB DEBUTED IN THE NICHOLS ARBORETUM AS PART OF A THREE-YEAR FORD MOTOR CO. GRANT FOR ARTS.

The RC company is now an Ann Arbor tradition. With no fixed stage, performers lead the audience to different locations in the Arb. U-M students, alumni, and faculty act in the performances.

2001: IN A STRATEGIC PLAN, THE RC FACULTY OFFERED LSA UNDERGRADUATES THE CHANCE TO MINOR IN CLASSES THAT WERE PART OF RC MAJORS, SUCH AS URBAN STUDIES, CRIME AND JUSTICE, GLOBALIZATION, AND THE ENVIRONMENT.

Although RC students were always allowed to choose majors within LSA, it was not until 2012 that RC majors were opened to LSA students. In the 2016-17 academic year, the RC graduating class earned degrees from 36 different majors between the two units.

2008: THE RC LAUNCHED THE SEMESTER IN DETROIT PROGRAM, WHICH IS OPEN TO ALL UNDERGRADUATES.

The program’s curriculum includes urban planning, history, and creative writing, and students live and work in the city and interact with dozens community leaders and activists. A recent survey showed that 36 percent of the students in the program’s 2012 cohort currently reside in Detroit.

2012: EAST QUAD BEGAN A MUCH-NEEDED 18-MONTH RENOVATION.

The project displaced RC students and classes across campus but galvanized the community to meet up and maintain solidarity.

2017: THE RC PLANS A 50TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION ON OCT. 19-22, 2017.

Festivities include lectures by current and former professors, an alumni art show in the RC Gallery, a night of drama and music in the Keene Theater, a Semester in Detroit bus tour, and tours of the RC given by current students.

Correction appended: A photo caption in the fall 2017 print edition of this article mistakenly identified Professor Charlie Bright teaching a first-year seminar in the 1970s as Professor Carl Cohen.

Jennifer Conlin, ’83, is deputy editor of Michigan Alumnus.