15 Years of LEADing the Way

•

Photos courtesy of LEAD Scholars.

Since the program’s inception in 2008, 758 LEAD Scholars have passed through the University of Michigan.

These underrepresented minority students were accepted into U-M because they are some of the brightest and best students in the country and they were chosen as LEAD Scholars because they exemplify the program’s four pillars: Leadership, Excellence, Achievement, and Diversity.

Here, four Scholars explain what this one program means to them.

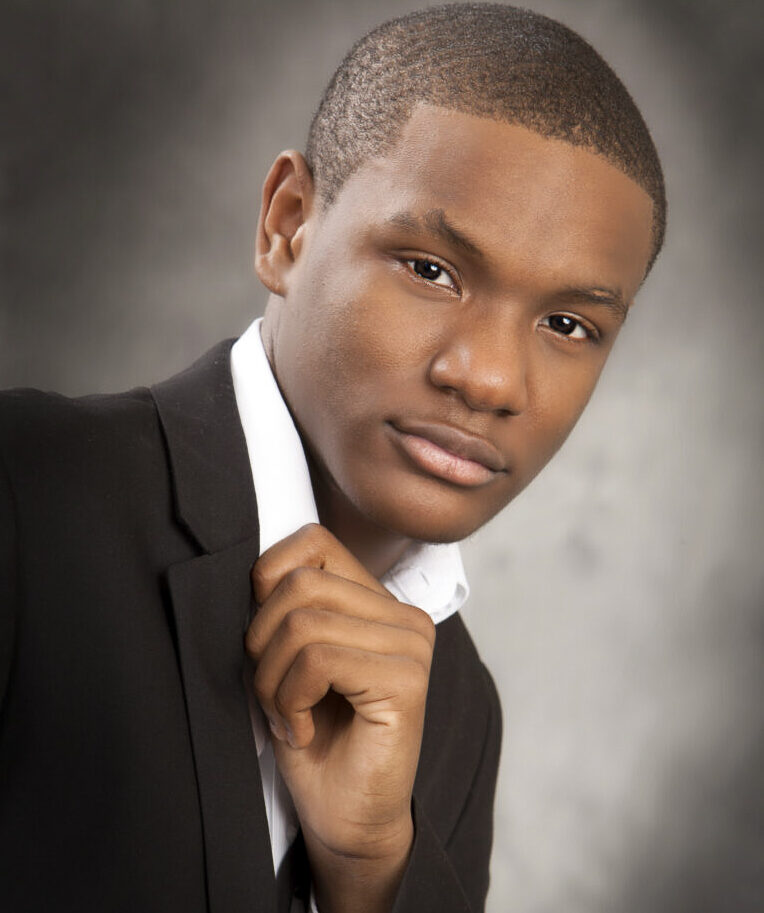

Mark Onuigbo, ’12

Mark Onuigbo, ’12, came to campus in 2008 as one of the very first LEAD Scholars of the program’s history. He left as an aerospace engineer.

For him, LEAD was transformative.

“I remember who I was before I went through [the University of] Michigan as a LEAD Scholar, and I remember who I was coming out of it. And even though it was only four years, the time there basically served as the basis of who I am today, and that’s a very different person than I was coming into Michigan.”

Today, a mere 4.1 percent of aerospace engineers are Black, and Onuigbo is among them. His endeavors and who they’ve shaped him to become are now part of a larger history — one of Black trailblazers who have made significant strides in aerospace as pilots, engineers, innovators, and leaders.

As a first-year student, Onuigbo joined the Student Space Systems Fabrication Laboratory, a collaboration of three aerospace engineering design teams at U-M dedicated to providing students with practical space systems experience not readily available through the academic curriculum.

In his sophomore year, he was named a recipient of the SMART Scholarship, which provides STEM students with full tuition, annual stipends, and employment with the Department of Defense after graduation. Come junior year, Onuigbo was a member of an undergraduate research project team working on solar-powered unmanned aerial vehicles, called solar bubbles. By his senior year, he took over as the team lead for the entire airframe vehicle.

Every single one of those [Scholars] is having a great impact and more than likely a multiplicative effect on the folks around them.

-- Mark Onuigbo, ’12

“One of the things that LEAD and Michigan baked into me was that there’s nothing we can’t do,” he says. “I really feel like the core of who I am as an engineer, as a person, and as a leader was seeded into me and really grown at Michigan and through LEAD. And I’ve been able to build upon it as I have gone through my career.”

With his coveted U-M aerospace engineering degree in hand, Onuigbo moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 2012 and began his career as a systems engineer at the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center. Six months into the job, he was assigned the role of leading the development of a weapons aircraft interface.

By 2017, he’d earned his master’s degree in aerospace, aeronautical, and astronautical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology. He’s spent the past seven years at Sandia National Laboratories as a systems engineer working on nuclear deterrence projects, leading teams as large as 20 people with budgets as large as $20 million.

Onuigbo’s journey gives credence to the idea that programs like LEAD make these success stories less anomalous for underrepresented minority students.

“You rarely see people of color in certain roles. I feel like one of the challenges, either subconsciously or consciously, is maybe implying that they’re not meant to be in those roles, or there’s something explicit [about] who they are that makes them incapable of being in those roles,” he says. “So something that’s made me super proud is that I feel like I’m helping to maybe change some of that perspective.”

He sees LEAD as a catalyst for building a diverse talent pipeline at the University that goes on to impact global industries.

“I think one of the key things that LEAD does is bring people with diverse backgrounds and mindsets into an awesome program like Michigan and

allows them to not only have Michigan imprinted on themselves, but have them imprinted on Michigan and the folks around them,” he says. “I feel like the more that we have the opportunity to bring in more diversity to the school and then into the industries that they then go on to work in, the better we all are.”

Fifteen years later, Onuigbo finds it “mind-blowing” to think about the hundreds of LEAD Scholars who have since been afforded the opportunity to pursue their dreams, become trailblazers, and make history — all because others chose to invest in their future.

“Every single one of those [Scholars] is having a great impact and more than likely a multiplicative effect on the folks around them,” he says.

“It seems like the good that the people coming out of LEAD are doing, or the impact that they’re making is an amazing investment that you can’t even quantify. This is the best investment that you can ever make if your goal is to have a greater impact on the world around us.”

Cheyenne Travioli, ’18

Cheyenne Travioli, ’18, reveres LEAD as “home,” where she became rooted in her identity as a Native American woman.

Named after her reservation, Travioli is a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe of the Lakota Nation. She grew up in Morenci, Michigan, a small rural town where her mother was raised by an adoptive family after being displaced from her reservation when she was just 6 years old.

“As a Lakota woman, the passion and the pride were always there, but because of LEAD and its student body, I was given a safe space to fully explore that identity,” she says.

Travioli’s lifelong dream of studying orthodontics at U-M halted after a “tumultuous” first semester, prompting her academic hiatus during the winter term.

It wasn’t until returning to campus and immersing herself in the LEAD community that Travioli felt called home — to herself, her culture, and her greater purpose.

“LEAD is a big piece of what helped me return to campus … I had a sense of belonging there. I didn’t feel so alone,” she says. “Meeting other students of color, I was able to resonate with similarities, even differences, in our backgrounds and our upbringing.”

Through LEAD, Travioli discovered a “deeper calling” to dedicate her life’s work to Indigenous studies and social justice, switching her academic route to art history and Native American studies. She joined the LEAD Advisory Board as the mentorship chair, later serving as the vice president.

The alum credits LEAD for helping her gain self-awareness and find confidence in her own voice, which she says ultimately opened the door to her involvement in other organizations. She used these opportunities to share her culture and increase awareness of challenges faced by Native Americans and students of other “invisible” identities.

As a chair member of Martha Cook’s Multicultural Society, she planned events throughout November in honor of Native American Heritage Month. She promoted lectures through the American culture department. She even organized students within LEAD and Martha Cook to attend the U-M Annual Dance for Mother Earth PowWow.

Three years after thinking she may not return to U-M, Travioli was named Michigan Daily’s Student of the Year in 2018 for her undergraduate endeavors.

LEAD was there as a safe space, and it eventually helped me thrive.

--Cheyenne Travioli, ’18

Her passion for Indigenous studies further culminated in earning a master’s degree in history with a focus on Native American studies from Eastern Michigan University in 2022, followed by the journey toward a Ph.D. in American culture from U-M.

“Being a history major, I know the barriers that are systemically ingrained in our society and within our institutions to prevent students of color from attending our institutions,” she says.

“It’s hard for us to get these opportunities to attend these institutions anyway. We don’t get the same privileges or opportunities as our peers who are not students of color … and once we get into the college of our dreams, we have to face a ton of barriers. Even once we make it to that campus, we’re going up against a colonized institution that historically hasn’t always been there for the success of some of its students.”

Travioli says that organizations like LEAD are “vital to the survival of students of color, ensuring they succeed in every way that they are allowed,” especially with the recent Supreme Court ruling on affirmative action.

“I say that because of my personal experience in withdrawing my first year … LEAD was there as a safe space, and it eventually helped me thrive,” she says.

While her ultimate goal is to become a professor in Indigenous studies (at her alma mater, she hopes), she would also love to curate Indigenous art at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., or work with the Native American Graves Protection Act.

She recognizes the glaring possibility that, without the LEAD community in place, her life’s path could have been very different.

“I didn’t get that kind of support from the campus body or my advisor, but I found that in LEAD, and I was able to survive because of LEAD,” she says. “So, to me, LEAD was home.”

Alyson Grigsby, ’20, MA’21

As part of the 2016 LEAD Cohort, Alyson Grigsby’s, ’20, MA’21, entrance to campus life was contemporaneous with the 2016 election and, subsequently, a contentious political climate.

“There was a lot going on where many students of color did not feel welcome on campus. There was just a lot of antagonism going around,” Grigsby recalls.

Grigsby, who uses the pronouns they/ them, remembers stepping foot on U-M’s Ann Arbor campus days following a family tragedy only to be warmly greeted by name at the LEAD Open House, the program’s first community event of the academic year.

The sense of belonging they felt — knowing that their voice, identity, and personal experiences have a place within systems and institutions where, historically, voices like theirs have been drowned out — is what Grigsby remembers so vividly about LEAD. And the safety and security they felt in the LEAD community inspired them to contribute to that same experience for other students.

“I really just felt a need to carve out spaces … deliberately work within certain programs to make it known that we want to make this campus a welcoming space,” Grigsby says.

That’s why they spent their undergraduate years at U-M immersed in communities and student organizations focused on improving campus resources and experiences for underrepresented students. It’s also why they’ve chosen to begin their career empowering voters to achieve structural and systemic democracy reform in Michigan.

Grigsby served as the communications chair for the LEAD Advisory Board and a creative mentor for the Lloyd Scholars for Writing and the Arts. As a peer information consultant for the U-M Library, they helped underrepresented minority students navigate the library’s vast services and resources. During their time as a member of the Inclusive Campus Collaborative, they joined the collective work of other diverse faculty, staff, and students, aiming to improve the U-M climate for students of all identities.

I really just felt a need to carve out spaces … deliberately work within certain programs to make it known that we want to make this campus a welcoming space.

-- Alyson Grisgby, ’20, MA’21

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s degree in transcultural studies, Grigsby went to work for Voters Not Politicians (VNP) and the VNP Education Fund. The Michigan-based grassroots nonprofit works to expand democracy in the state through voter education and direct engagement with local political leaders with the goal of abolishing gerrymandering in Michigan.

Grigsby began as the education program manager, working directly with VNP’s community mapping program, collaborating with volunteers to help various engagement partners across the state participate in the 2020 redistricting process.

As a civic engagement manager, Grigsby also assists in various VNP initiatives, working with local clerks and municipalities across Michigan to increase access to voting, particularly in lowturnout areas. The goal, Grigsby says, is ensuring that people can take advantage of the new voting rights for which VNP has been advocating.

“We are primarily focusing on local and state politics because we found that a lot of political change can happen by engaging with your state legislators or even with your local governments,” Grigsby says.

Grigsby helped expand these efforts within the classrooms of their alma mater, entering political science classes at UMDearborn. They educated students on drawing district maps and talking about their communities, helping them “look at this as a historical process of how we can end political gerrymandering and give Michiganders more representation.”

For Grigsby, increasing representation has always been the greater mission. When Grigsby hears “this number” — 758 LEAD Scholars and alumni — they compare it to the hundreds of thousands of students at U-M alone. They can’t help but wonder how to expand the LEAD network and how to support more LEAD Scholars who are “going out into the world and making an impact in their various fields.”

“I guess it just makes me proud to think that [LEAD Scholars and alumni] are helping to contribute to creating a space on the campus where people of all different races and backgrounds can succeed,” Grigsby says.

“Being able to visualize it in a sense just makes me proud, knowing that we were all able to come into ourselves with all these various resources and benefit from learning from each other and trying to help expand what a U-M student looks like on this campus.”

Caleb Middleton

Once an elementary schooler sitting behind the keys of an old piano with his sight set on Julliard and New York University, Caleb Middleton is now standing in front of entire orchestras for some of the top student theatrical productions at U-M.

He’s set to graduate from the School of Music, Theatre, and Dance (SMTD) in May 2024, but when he thinks back on the art he’s created or been a part of at U-M, he thinks of the community that brought it to life — his creative partners, the other students of color telling stories to uplift marginalized voices.

“I feel like there’s nothing that I can’t do with this community that LEAD has built in my corner,” he says.

“I was able to meet people [through LEAD] on a level of being Black students here at the University pursuing a career where there’s not really a lot of us.”

Middleton knew it was U-M where he’d pursue a music degree after performing with the all-state national choir his first year of high school, directed by Eugene Rogers, MMUS’01, AMusD’08, professor and director of choral activities at U-M. It was the first time he’d ever seen a Black man conduct a choir.

“[He was] a Black leader in classical music, at that capacity, at that level, and he was from the University of Michigan. So I was like, ‘Oh, I want to meet him. I want to study with him. I want to be just like him,’” he says.

Middleton is well on his way.

During his time at U-M, he directed, conducted, supervised, or orchestrated the music in nearly a dozen student musical productions. Most have been MUSKET productions, U-M’s oldest student-run musical theater organization, which produces two shows each academic year.

He joined MUSKET his first year, playing piano for rehearsals. He became assistant director, then associate director, and, by his junior year, the lead music director for both shows.

“If I didn’t have the circle that LEAD has built and that I built through SMTD, I don’t think I would have the strength to pursue these opportunities and to go against all the pushback that [students of color] experience through the University. But within the LEAD community, I feel like I had that support and people in my corner that will help me provide opportunities for people who aren’t in LEAD or who don’t have those opportunities.”

Some shows were independently produced through collaborations with other campus creators, many of whom were SMTD students Middleton met through LEAD, like his directing partner, Chloe Cuff, ’23.

In honor of Black History Month, he and fellow LEAD Scholar Aidan Jones joined forces to direct an independently produced version of “The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin.” He calls it a “gorgeous” story about a young Black girl on her journey to “finding her Blackness” and discovering how she operates in a world where people see her for the color of her skin.

They received funding from LEAD for the production venue but were exploring grants and other funding opportunities to expand the costume and hair budgets and pay their team.

That’s when the group discovered Songs for Democracy, a competition inviting students to compose original musical works to inspire the participation that a functioning and thriving democracy requires. The directions were vague: write a song about democracy with original music and lyrics.

Middleton wrote the music, producer Cortez Hill wrote the lyrics, and they performed it in front of judges at Hill Auditorium, with Jones and “Bubbly” lead Oluchi Nwaokorie singing and rapping the verses.

They won the first-place grand prize of $3,000, which went toward the February 2023 production of “Bubbly.”

“We were able to use that money to produce a show that we were passionate about and tell a story that’s not really told,” he says. “The story of the endurance and the power of Black women.”

I feel like that’s what LEAD is — it’s people that are destined for greatness and building them up to do great things.

-- Caleb Middleton

That’s always been the goal for Middleton: creating art not only for all performers of color but specifically for Black men, women, and queer people of color.

“There’s not a lot of opportunities out there, and even when there are … it’s focused on the struggle of Black artists,” he says. “Not a lot of it celebrates the joy in the strength of the things that we have endured.”

Middleton will spend the fall of his senior year as the assistant for the musical theatre department, focusing on graduate school applications. He’s dedicating his spring semester to his senior thesis and a final recital before walking the stage at spring 2024 commencement.

Post-graduation, he plans to attend graduate school for conducting or music directing or head to New York to book an industry job playing or directing music.

Wherever he goes next, Middleton is proud to be a LEAD Scholar. He says he’s proud to wear the name of the program on his shirt for the world to see because it shows others that he’s someone who is bound to do great things.

“I feel like that’s what LEAD is — it’s people that are destined for greatness and building them up to do great things. So for me, when I represent the LEAD Scholars, it’s just knowing that I have 15 generations on my back and then more to come.”

Katie Frankhart is a senior writer at the Alumni Association of the University of Michigan.