Michigan’s governor banned public gatherings at theaters and churches. A cottage industry of face-mask makers sprang up. The sports arenas and fields fell silent. Hospital wards overflowed, and many local public schools closed. Questions abounded as to whether public officials were sugarcoating the situation for political purposes and, in the process, harming the effort to contain the epidemic. A debate raged over the balance between the need to protect the public and the economic harm caused by doing so.

This was Ann Arbor in October 1918.

As the influenza pandemic swept through the Wolverine State, it disrupted ordinary life in ways unimaginable to 21st century Americans — until now. Nationwide, that health crisis took possibly 675,000 lives, including more than 15,000 in Michigan (the equivalent of 50,000 today, based on the state’s current population). The death toll in Ann Arbor was said to be 117, although historians view that as a significant undercount as it appears health officials stopped counting in early November 1918 and the epidemic had at least one major resurgence.

“The comparisons between the flu of 1918 and COVID-19 is how widespread the cases are in both pandemics and the similarity in the restrictions that cities and states implemented,” says historian J. Alexander Navarro, assistant director of U-M’s Center for the History of Medicine. “There are a lot of similarities and good reason why we’re looking back to 1918, but it’s also important to remember the historical contexts are different.”

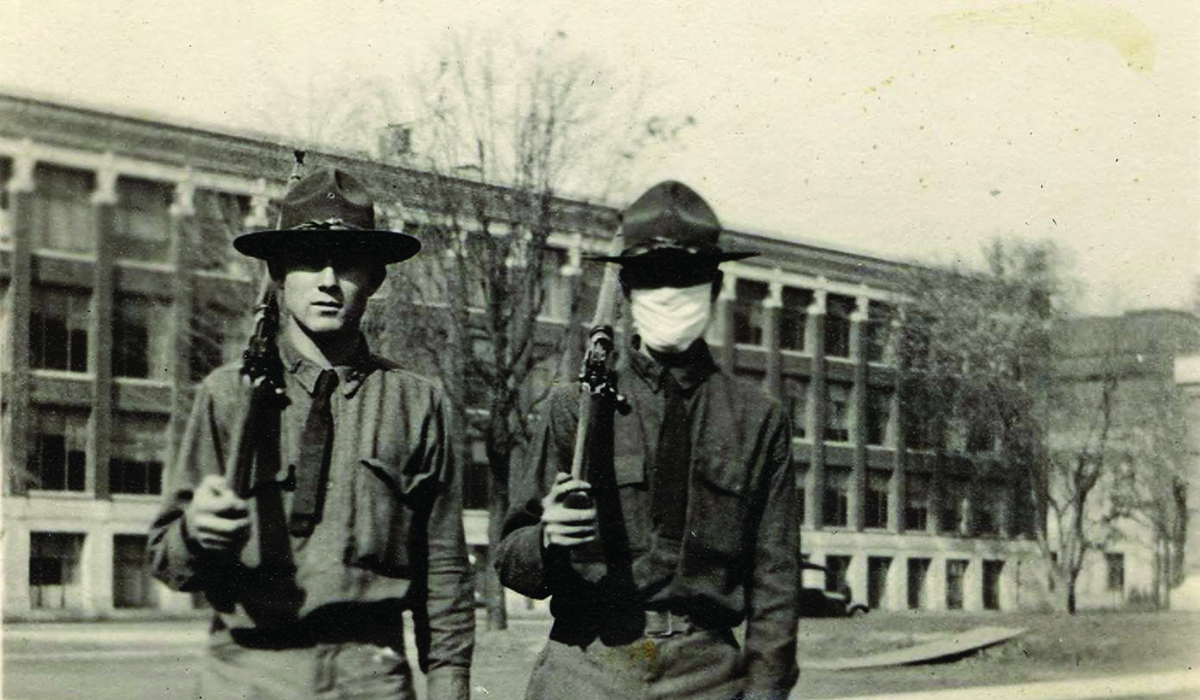

Indeed, the end stages of World War I occupied everyone’s attention and most of the local press coverage. The war ended Nov. 11, 1918, so some of the most significant Allied victories coincided with the weeks when the epidemic gripped Michigan and then waned in the state. But more than 4,000 U-M men were enlisted in the Student Army Training Corps (SATC), which enabled them to continue their studies on campus while also gearing up for possible deployment in Europe. The close quarters of barrack life facilitated the rapid spread of the deadly flu.

It is difficult to discern from the coverage in The Michigan Daily and other local papers how scary the epidemic seemed. Journalists of that era mainly stuck to official data and statements and published interviews with few “real people” — students, faculty, patients, and medical workers. This was part of a larger effort by leaders across the country to minimize the impact of the pandemic.

And even as the flu ravaged a military base in western Michigan and surged into Detroit, Ann Arbor’s public health officer, J.A. Wessinger, and the dean of U-M’s Medical School, Victor C. Vaughan, MS1875, PhD1876, MD1878, HLLD1900, downplayed its local impact. On Oct. 1, Vaughan dismissed the disease in the Detroit Free Press as “only old-fashioned grip,” the general term then used for influenza. The Daily’s Oct. 3 report on the first 12 local cases was headlined “Student Body Free From Influenza” and relied on Wessinger to suggest that the “disease is not feared here due to good conditions.” Two days later, with four new cases reported, Wessinger “confidently believes it will subside within the next 10 days.”

Yet by Oct. 13, with more than 500 reported cases — including 225 SATC enlistees — and the death of a 23-year-old chemistry instructor, The Daily’s editorial board unloaded on officials who claimed the epidemic wasn’t serious. The military, the paper noted, seemed alarmed enough to bar enlistees from attending theaters and to require medics to interact with patients only when donning masks.

Within days, the public response shifted dramatically. University President Harry Burns Hutchins issued an edict requiring faculty and students to “wear, until further notice, face masks while on the streets and campus, at all university exercises and in rooming houses.” This launched a campaign in which the local forces of the Red Cross, supplemented by female U-M students, sewed thousands of masks that the coeds then handed out to students heading to class. The masks prompted jokes and controversy; a Daily story headlined “Beauty and Beast Both Camouflaged” bemoaned the notion that women could go without makeup and men unshaven under their masks.

As the number of cases increased, the dining room of the old Michigan Union — which was in the process of being replaced by the current building — became an infirmary for recovering patients. The women’s athletic center, Barbour Gymnasium, became a “hospital clearinghouse” where newly ill patients went for observation. Local women also took in some recovering patients, and plans were made to refit Newberry Hall, which today is the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, as an infirmary. It’s unclear if that ever happened.

The Daily repeatedly published guides to prevention and personal hygiene that students could easily follow in today’s COVID-19 world: wash their hands frequently, avoid touching their faces and mouths, use utensils only after they were cleaned with scalding water, stay away from crowds, and go to bed if sick.

“A lot of today’s orders are more sweeping than they were in 1918 in large part because public health officials took those lessons of 1918 and realized that, short of having a pharmaceutical intervention or drug therapy, you had to implement these non-pharmaceutical interventions to mitigate the disease,” Navarro says. “But even then, you see public health officials telling everyone to remain at least 6 feet apart because they know it is transmitted through respiratory droplets.”

Then, as now, U-M researchers and resources were deployed to devise treatments and cures or to address health care needs. On Oct. 17, the Free Press told of a student medic in the SATC who “is at work on an anti-streptococcus serum … used on three men in a hospital here after hope had been abandoned. They are recovering.” Two days later, Medical School officials expected their seniors to be called up to relieve doctors around the state “overworked with the rush of patients.” Engineering students, meanwhile, were dispatched to the SATC barracks to assess their cleanliness, The Daily reported on Oct. 23.

“It’s kind of strange to that this this major pandemic that killed as many as maybe 675,000 Americans didn’t have a much more lasting impact.”

The governor and the state board of health forced the closure of certain public venues for two weeks ending on Nov. 9, and many school districts, including Ann Arbor, had already canceled classes by then. U-M, however, remained in session throughout the epidemic. The Daily reported on high absenteeism, but in general instruction continued unabated.

“Regarding the closing of the University, Captain Vaughan said that it might have proved a very excellent measure at the outbreak of the epidemic, but that he sees no essential reason for such action now,” The Daily reported on Oct. 19.

One disruption that did occur to much fanfare: the cancellation of some football games and the one-month postponement of the all-important meetup between the Wolverines and a university then called the Michigan Agricultural College. (The team was known as the Aggies before a contest held in 1925 rechristened them the Spartans.) “Varsity Gridiron Schedule Wrecked By Flu Epidemic,” a Daily headline screamed on Oct. 24, when the Nov. 2 clash between Michigan and Northwestern was called off. It was the third canceled game. (Four games were played in November, including a Nov. 30 shutout of Ohio State, with Michigan ending the season undefeated and crowned the national champions.)

By the second week of November 1918, life began returning to normal — theaters and schools reopened, volume at local hospitals was restored to manageable levels — as the number of new flu cases dropped and the public celebrated the triumph of World War I. On Nov. 5, in fact, The Daily reported that the University wanted flu masks returned “for they are needed badly by the nurses and those who are working in the various hospitals.”

“Society just went back to normal operations,” Navarro says. “People grieved if they had lost a loved one, but people went back to shopping, they largely went back to congregating. As soon as they lifted the measure, people just flocked to the theaters. It’s kind of strange to think that this major pandemic that killed as many as maybe 675,000 Americans didn’t have a much more lasting impact on how the United States acted after that.”

Steve Friess is news and features editor at Hour Detroit and a Newsweek contributing writer.