World War I made an impact on all areas of the University, whether in sending its students and faculty off to serve or opening up its buildings to train and house soldiers. During the war, Michigan Alumnus faithfully chronicled those efforts.

“The country is in a state of war—real war—such as we have not had for fifty years … . In the last days of March steps were taken to place the University among the ranks of other American institutions that are making their resources available for the use of the nation.”

When Michigan Alumnus published those words in April 1917, the United States had just entered World War I and an uncertain future lay ahead for the University, the country, and the world. Beginning with that issue and well into 1919, the then-monthly publication of the magazine chronicled the effect of the war on the campus and its community.

Throughout those months, the magazine carried the usual U-M news and information—the production of the annual May Festival and other campus entertainments, reports on board of regents meetings, athletic updates, book reviews, and class notes. Notable are details about the construction of the Michigan Union and the University of Michigan Library (now the Hatcher Graduate Library), both of which began before the war.

But new content made its way into the magazine: First, the long lists of students, faculty, and alumni in the service. And, within months, memorials to those who had fallen. “Letters From the Front,” first appearing in October 1917, continued through the end of the war. Writers initially detailed their experiences in training and arriving overseas; eventually, they described the action they saw on the battlefield.

The impact of the war also reached back home, to every corner of campus. With so many in the service, enrollments declined, measurably affecting the graduating class of 1918. “No one present at the Commencement Exercises failed to be moved by the flag with 473 stars that represented the members of the class of 1918 in service,” reads the August issue of the magazine.

Even the Michigan Daily felt the effects, according to the November 1918 issue of Michigan Alumnus, citing the fact that many of its editors and reporters had left: “An early rumor had it that The Michigan Daily would be compelled to suspend publication for want of a competent staff.”

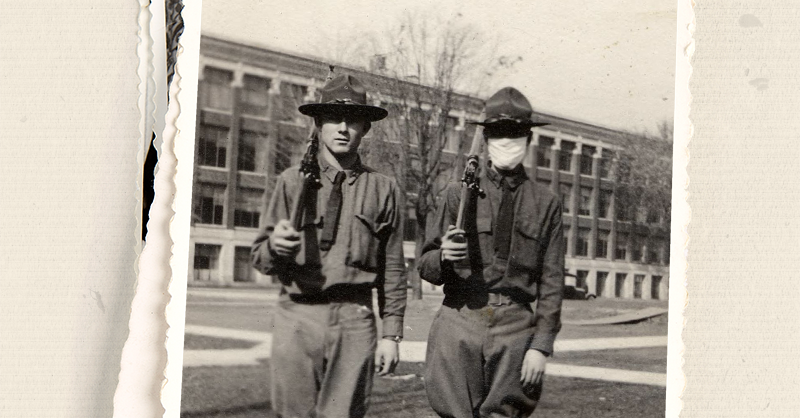

However, even as many people departed campus, others arrived. As at other universities across the country, soldiers came to U-M to train at the many facilities that had been repurposed for the war. Ferry Field, then home to the football team, and other open spaces were used for drills. The newly constructed Michigan Union was one of the facilities used as barracks and mess halls. Barbour Gymnasium and, later, Alumni Memorial Hall (former home of the Alumni Association and current location of the U-M Museum of Art) became the Hostess House, one of many around the country set up as a social space for soldiers and their female friends and relatives.

By April 1918, Michigan Alumnus noted the impact of the war on campus: “The University itself is rapidly bending all its energies, actual and potential, towards the task in hand. Every day almost finds a new avenue for effort opening. If the war continues for more than another year, it is safe to say that there will be no department of the University which will not find its field of usefulness and be upon a war basis.”

But the war did not continue “for more than another year,” ending later in 1918. Soon after that, buildings and grounds returned to their original purpose, soldiers in training departed, and students and faculty came home.

The magazine, however, continued to share stories of war, including a journal written by William B. Campbell, 1917, during his service in France with the U.S. Naval Railway Battery. In observance of the 100th anniversary of the end of the war, we share his journal entry dated Nov. 11, 1918 (below).

More digging. The clay is hard. The weather is fine,—that of the “golden November” of the popular song. At 9:30 A. M. a French sergeant came rapidly walking up the track. He said something to the Frenchmen working on the tracks; several of them shouted. The sergeant’s face was red from fast walking, but he looked happy. He came immediately to his lieutenant with a slip of paper. We crowded up and the latter read a brief announcement that the armistice would begin at eleven o’clock this morning and that the Allied armies would hold the lines attained at that time. Everybody whooped. The sergeant told me that the news had been received at 5:00 A. M. via radio.

In a few minutes Lieutenant Duckett came and ordered us to knock off and load all materials on the car. More whoops.—We had the afternoon off.—It seems that the fighting ceased for the first time in over four years, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of this year.

Evening: Arch (A. G. Wenley, ’20) and I walked over to the village. Bells have been ringing all day, and whistles blowing. The buvettes (bars) were crowded with poilus (French infantrymen). We found one where the beer wasn’t exhausted. There we met three Frenchmen with whom we talked and drank. We couldn’t pay for the first few bottles: they insisted. “Mais c’ est la Victoire, c’est la Victoire!” One tried to tell me how that without America, France would have been lost; then it was “Vive l’Amerique! Vive les Americains!”

Later a couple of our fellows came in, and one started singing a snatch of a tune. (The Frenchmen had all been talking, laughing, and singing). Then I heard a clamor and Pigott (the singer) leaned over to ask me what chanter meant. I told him. “They want me to chanter,” he said. Then the man opposite me at the table, who looked much like Professor Pillsbury, asked me what the English word for chanter was. I told him. “Sing, sing!” he cried to Piggott, and the rest took it up. Then all “sh-sh-” ed; he didn’t know what to sing. One suggested, “Teepairaree, Teepairaree!” So he sang Tipperary, amid wild applause. The French wanted more, so all of us sang “I was drunk last night” and “Glorious, glorious!” Then I got a poilu to sing “Madelon.”

We departed for the train, in the Forêt de Mondon, about 7:30 p. m. A half-moon through the misty heaven lit our way.

Sharon Morioka, ’84, MA’86, is the editor of Michigan Alumnus.