Imagine being able to take a few minutes between classes to relax with the University’s otters, turtles, bears, and wolverine. For over 30 years, this was a viable activity.

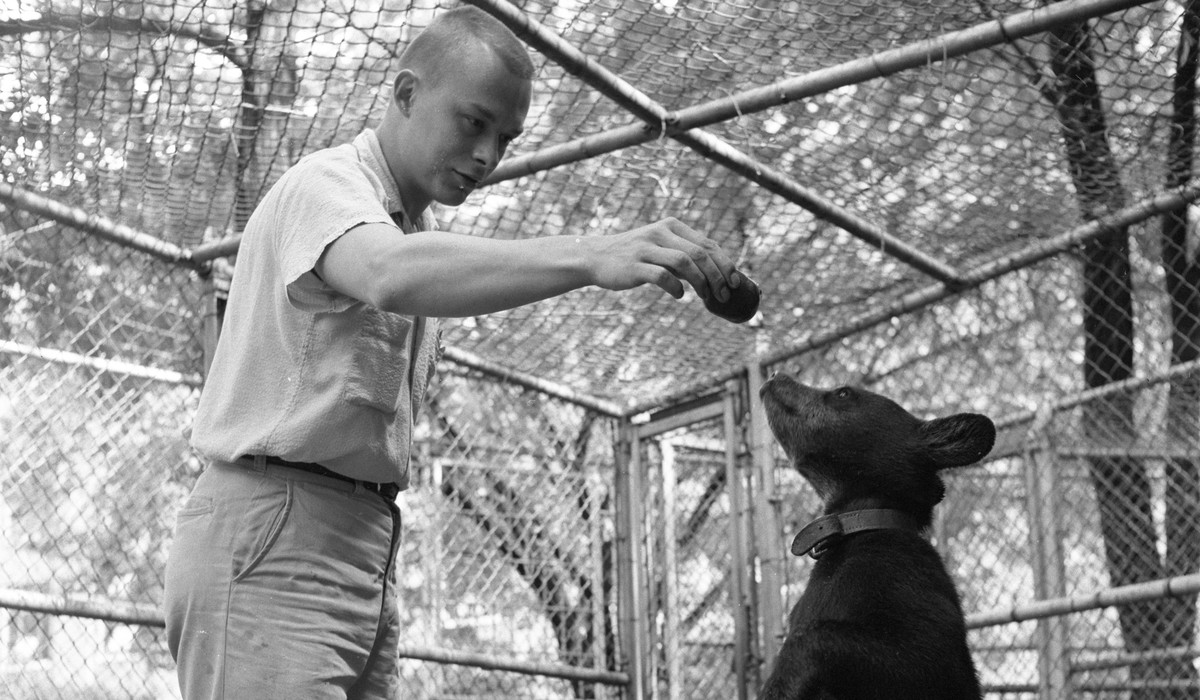

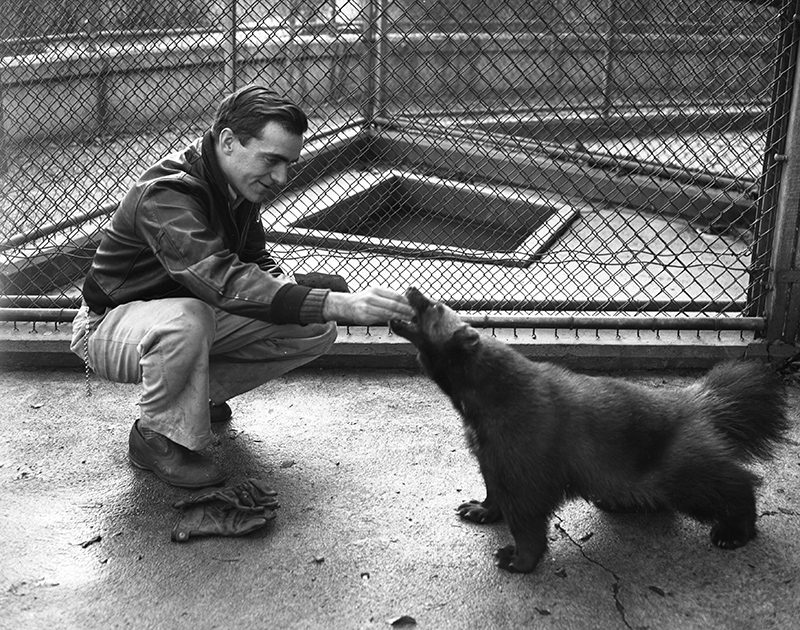

In 1929, an anonymous benefactor paid for the construction of a small zoo behind the Alexander G. Ruthven Museums Building on Washtenaw Avenue, which completed construction a year earlier. The benefits to general public and scientific interests were obvious, but the donor especially hoped it would bring comfort to the children in University Hospital across the street (now North Hall). The benefactor provided the initial collection of animals: a badger, a red fox, six raccoons, two porcupines, four skunks, and two black bears.

The hexagonal building and its pens proved an immediate hit. Students and families stopped by to watch the animals, while the zoo served as a teaching tool for the museums and researchers. By the next year, the “animal house” added a reptile pit to accommodate snakes and turtles. Over the years, the U-M zoo came to include opossums, otters, coyotes, and more.

Video by Rob Hess for LSA Magazine, footage from Bentley Historical Library.

By design, all of these species were native to the state. One exception was U-M’s mascot.

A few wolverines did reside at the U-M zoo. When football coach/athletic director Fielding Yost sought to rouse spirits by showing off live wolverines at games, he struck a deal to have two Alaskan imports residing at the Detroit Zoo—Bennie and Biff—transported in for big games, beginning with Michigan Stadium’s dedication in 1927. Inevitably, safety became a concern as the duo grew larger and too ornery to keep in the U-M zoo, never mind parading them on field in cages, and so they eventually returned to Detroit.

A final attempt at a live mascot was made in 1936 after Chevrolet Motor Co. gifted a wolverine to the athletic department. However, the animal’s run was limited to a single game as museum experts protested the practice. Treppy, short for Intrepidas, was apparently more approachable than his predecessors (for his species, at least) and lived a relatively long life at the U-M zoo until his death of natural causes in 1950.

After several years of operation, a much, much loftier vision for U-M’s zoological offerings emerged. C.B. Troedson, an architect and visiting professor from the University of Southern California, spearheaded a 1938 initiative to turn 40 acres, near the present location of Nichols Arboretum, into an outdoor museum/zoological garden.

Inspired by the Detroit Zoo, the layout would house the animals, U-M’s zoo residents included, in cage-free, moat-encircled enclosures—beaver dams on the Huron River here, a bear mound there. Pedestrian trails, a railway system, and picnic spaces would complete the visitor experience. At least some U-M faculty and administration were on board; the thinking was that the Works Progress Administration would provide funding. But the plans never came to fruition for unknown reasons.

Although the zoo was still popular by the early 1960s, U-M’s campus was evolving. A $1 million expansion to the Ruthven Museums Building included the zoo’s grounds. Members of the Ann Arbor City Council and community pushed for the zoo to be saved or moved, but it was not to be. The animals were relocated to other vetted zoos, and the facility was razed in September 1962.

But, as the song goes, it’s the circle of life. Maize and Blue, a pair of brown bears that came to U-M as cubs in 1957, landed in a zoo south of Battle Creek, Michigan. The two birthed a cub in 1964.

Gregory Lucas-Myers, ’10, is senior assistant editor of Michigan Alumnus.