Michigan’s Great Assets

•

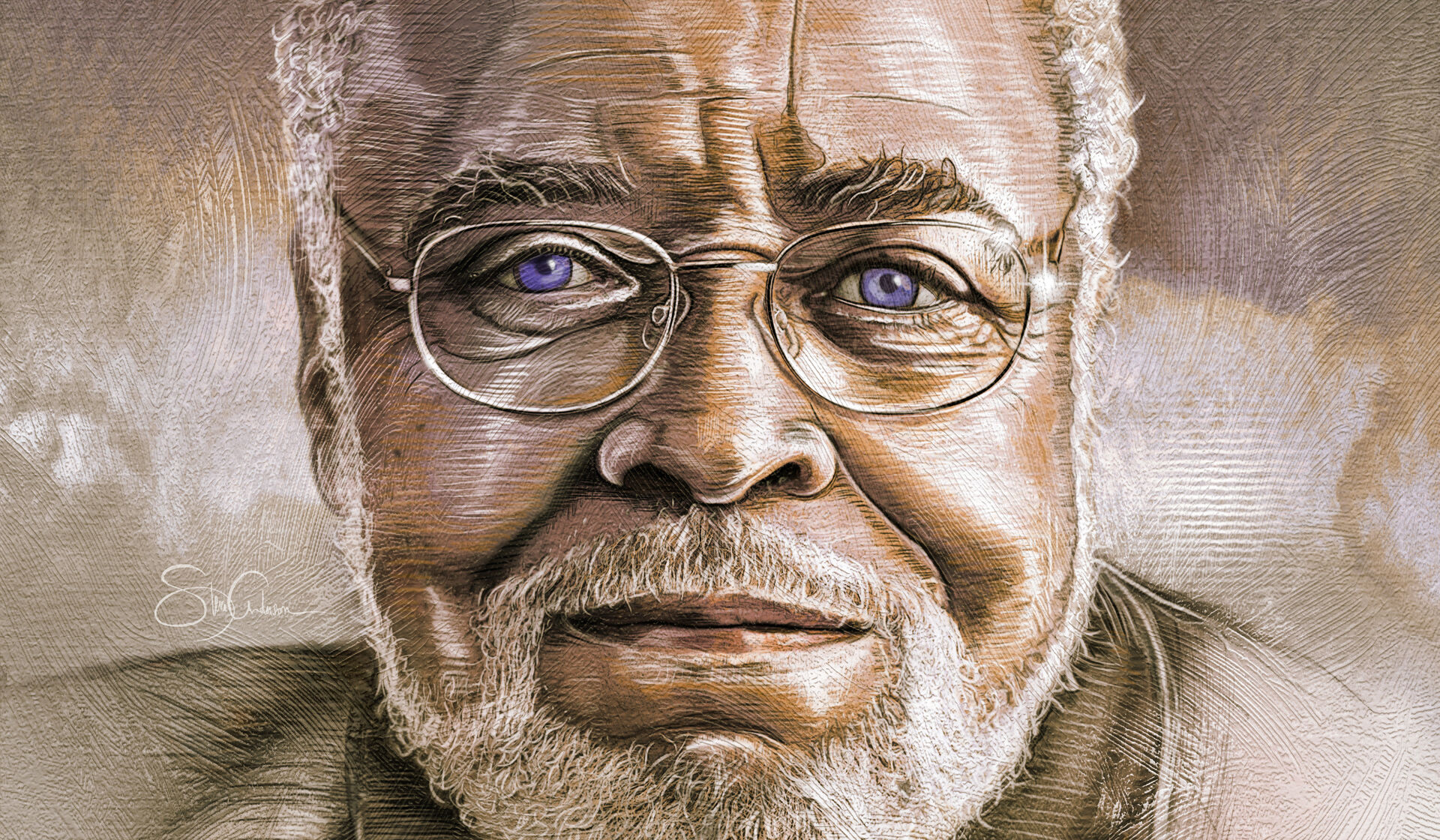

Photo by Todd Marsee, Michigan Sea GranT

Michigan boasts 3,000 miles of shoreline access to the Great Lakes, which house 20 percent of the Earth’s freshwater. It’s a resource that’s made the Great Lakes region popular amid climate change concerns, natural disasters, and water scarcity in other areas of the U.S., but the Great Lakes are still subject to serious vulnerabilities.

“I definitely think that there’s an impression that the Great Lakes take care of themselves. That if you’re not involved in any of the conservation or management, you would have no idea how many thousands of people’s job it is to make sure that there are fish out there when you want to go fishing. Keeping the Great Lakes safe, keeping the water quality good, is a multinational jurisdictional issue that thousands of people are working on any given moment,” says Silvia Santa Maria Newell, director of Michigan Sea Grant and professor at U-M’s School of Environment and Sustainability.

Michigan Sea Grant funds research, education, and outreach projects designed to foster science-based decisions about the use and conservation of Great Lakes resources. It’s one of many organizations across the region that supports Great Lakes sustainability and conservation, but as part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s national Sea Grant network, Michigan Sea Grant bridges federal funding and Michigan-specific solutions.

“Sea Grant is about bringing people together, but across communities. It funds sciences directly relevant to state priorities,” Newell says.

A Michigan Partnership

Michigan Sea Grant is a cooperative program of U-M and Michigan State University (MSU). Collaboration between schools allows Michigan Sea Grant to leverage U-M’s research strengths while accessing MSU’s vast connections through their MSU Extension programs. In 2023 alone, Michigan Sea Grant engaged nearly 16,000 people in informal education programs and nearly 9,000 K-12 students. The same year, more than $8.7 million in economic benefits were derived from Michigan Sea Grant activities.

The program offers programs such as a 4-H natural resources camp for K-12 students and Paddle Stewards training, which teaches kayakers and other paddlers to identify, report, and prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species. It houses the Center for Great Lakes Literacy, a repository of Great Lakes-focused lesson plans for and by educators, and funds research projects, such as a currently ongoing one to determine how the lakes are responding to our changing winters — recent data shows the Great Lakes are losing 14 days of winter per decade.

“When we fund research, we’re only funding things that are going to turn and answer a question that’s needed to make decisions in our state. I think that makes it really special, to know that the research that gets done here is something that’s going to help our state move forward in some way,” Newell says.

Complex Issues

A 2024 poll by the Great Lakes Water Quality Board found that 94 percent of U.S. and Canadian residents in the region support the lakes’ protection. But researchers like Mike Shriberg, MS’00, PhD’02, say it’s not as straightforward to get residents to support solutions.

“[People] assume because the lakes have made a very visible comeback and clean up that the issues that are out there aren’t as serious as they used to be. What’s actually happening is our issues are getting more complex. . . . A lot of the problems now are less visible, but no less serious,” Shriberg says.

Some of those problems include pollution, changing temperatures, and, Newell says, invasive species. The sea lamprey is an invasive, parasitic fish in the Great Lakes, capable of killing up to 40 pounds of fish during its juvenile stage. Sea lamprey control efforts were reduced by 75 percent in 2020 and 25 percent in 2021 due to COVID-19-related travel restrictions. The result of this reduction of sea lamprey control cost fisheries nearly $290 million worth of fish. Though it has since been ameliorated, recent federally mandated hiring freezes nearly threatened Michigan’s ability to hire the people who conduct the species control.

Shriberg is the director of engagement for Michigan Sea Grant, as well as the associate director of the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research (CIGLR), a research institute and a regional consortium hosted by U-M’s School for the Environment and Sustainability, where Shriberg is a professor. He’s currently part of the research team for the Michigan the Beautiful: Great Lakes project at Michigan Sea Grant, which is assessing how Michigan’s coastal and Great Lakes waters can contribute to the United Nations’ goal of ensuring 30 percent of Earth’s land, coast, and open waters are under effective conservation and management by 2030.

For those looking to support Great Lakes conservation, Shriberg says it’s important for people to keep sustainability in mind with the many choices they make.

“Individual actions do matter. It’s what you drive, where you live, what you eat, and all those things add up to big impacts. But then the other thing is, what do you support? What do you support with your vote? What do you support with your consumer dollars?” Shriberg says.

Newell reinforces the importance of prioritizing Great Lakes sustainability.

“I went into this field 20 years ago with the idea that water would be the next gold, that freshwater is our most important natural resource that we can possibly protect. And we are lucky to have the lion’s share of it right here in our backyard,” Newell says. “Freshwater is and will be the most scarce resource at some point going forward. Everything that we can do to protect it is everything that it deserves.”

Katherine Fiorillo is the senior editor of Michigan Alum.