James Hathaway was not pleased. He had harbored high hopes for a September meeting of governments at the United Nations regarding refugees and migrants. Given the chaos across Europe in recent years involving the flood of Syrian refugees, he thought the world’s wealthiest nations were ready to revise a broken international asylum system.

Instead, the event “was a near-unmitigated disaster,” as he told those gathered at a late-October luncheon of the U-M Law School student organization Human Rights Advocates. Rather than make the system better, fairer, and a lot less costly, he said, officials from the U.N. High Commissioner on Refugees, which oversaw the proceedings, paid lip service to the need for reforms. UNHCR then called for another meeting—two years hence—to discuss the matter more.

“That,” Hathaway told his audience, “is not going to work. That is not what refugees deserve, and that’s not what countries like Lebanon and Turkey deserve. It’s not what anyone deserves in terms of a system that works functionally and dependably for refugee protection without imposing security costs.”

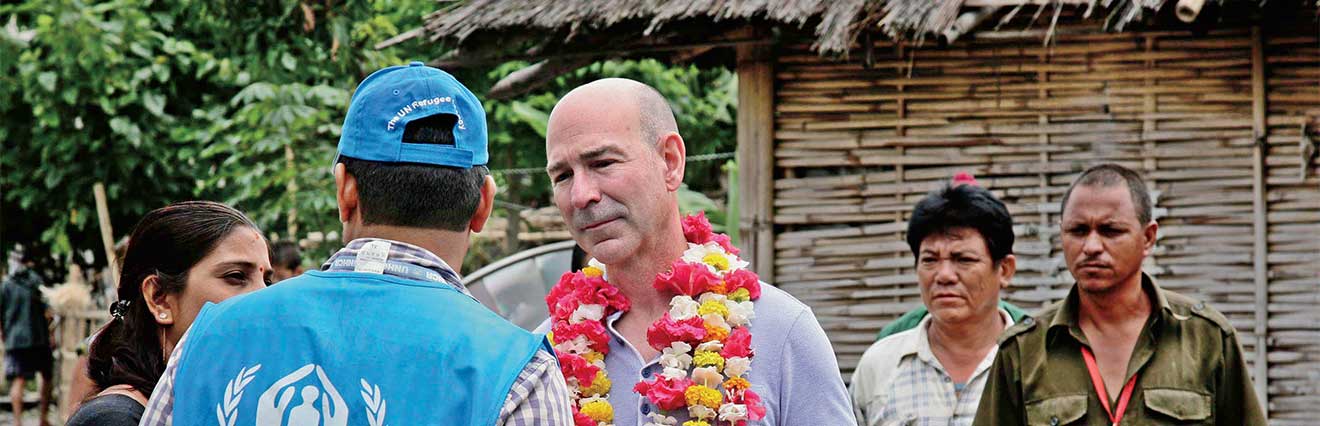

As it became clear to the luncheon audience, Hathaway is not merely an academic. He has been circling the globe for years advocating a new approach to the treatment of the 20 million people who risk their lives and abandon their homes and belongings to flee persecution. His perch as founder of U-M’s Program in Refugee and Asylum Law gives him an important soapbox. He also has been a singular figure on the international stage in this area since he emerged from graduate school at Columbia University and later authored “The Law of Refugee Status.” The 1991 book became the standard-bearing tome on the topic.

The solution Hathaway advocates would centralize the decisions on destinations and definitions of refugees within the U.N. Commission on Human Rights.

“It’s hard to understand just how important he is,” says Kelsey Van- Overloop, JD’15, who clerks for the District of Columbia Court of Appeals. “When you start reading case law on asylum from all around the world, it’s pretty amazing how many times he gets cited. It’s kind of mind-blowing that I got to sit in a classroom with him two or three times a week for many, many weeks and argue about refugee law.”

Hathaway, 60, first encountered this niche in the mid-1970s, when he worked for a semester in a legal clinic in a low-income Toronto neighborhood while getting his degree from Osgoode Hall Law School. A native of Canada, he had spent part of his childhood in Texas, thanks to his father’s job as an oil executive, where he learned to speak Spanish. Because of his fluency, Hathaway was assigned to handle the cases of Chilean refugees.

“My first refugee client was a 16-year-old from Chile who had been tortured by the secret police,” Hathaway says during an interview in his sparse, ninth-floor corner office in Hutchins Hall. “(A)s the head of the local football club, they assumed he was a leader of young men who were opposing Pinochet, which, in fact, he wasn’t.”

As an undergraduate at McGill University, he aspired to become a diplomat, so refugee law seemed like an appealing blend of foreign and legal affairs. “I loved the human connection with these clients, and I loved the ability to feel useful to people whose lives had been so miserable.” Hathaway spent the first part of the 1980s back at law school—this time at Columbia, where he received a doctor of the science of law and a master of laws degree—then in Canada teaching at a law school before working in the Canadian Department of Justice as a consultant. In 1984, he began a 14-year stint teaching law at Osgoode. But ever since his time at Columbia (where he had chosen to focus his dissertation on “the only thing that excited me, refugees”), he had been infuriated by what he had learned.

The 1951 U.N. Refugee Convention—an international treaty signed by 148 countries—obligates those countries to find solutions for the millions of people worldwide who have escaped homeland perils. However, most of those people festered in squalid conditions as stateless residents with no prospects of being able to work or move on; nearly half of refugees wait 20 years for a solution. While all signatories have technically agreed to the same broad definition of what qualifies as a refugee, Hathaway realized that “every country can decide for itself how to interpret that definition.” Wealthy, remote nations could afford to create complex, expensive systems to decide who receives asylum, while poor nations—often abutting the countries from which oppressed or endangered peoples flee—simply face an onslaught of human need that they are ill-equipped to handle.

By the time Hathaway was recruited to come to U-M in 1998 and start the program in refugee and asylum law, his 1991 book had made him an international star of this realm. His groundbreaking argument in the book seems obvious today: nations are obligated to define persecution that deserves asylum by “core human rights standards.” The theory sent shock waves through the world’s asylum courts, which began to adjudicate cases on that basis.

Hathaway started traveling the world, training refugee lawyers and lecturing to judges, thus positioning himself as the go-to authority on how laws are interpreted. He routinely addresses the International Association of Refugee Law Judges, a group whose members influence one another even when they don’t formally cite each other’s opinions.

To explain how his work bears fruit, he gave an example: “An American court wrote an opinion about what defines a refugee that I thought had a good theory, so I put it in my book. The Supreme Court of Canada found it in my book and said they thought it was a good idea. Then the British House of Lords cited the Canadian Supreme Court in making law. I was just an interlocutor.”

U-M students involved in his program see something more. Each year, about 40 of them take his collection of refugee and asylum classes, and, of those, 10 are chosen to plan and participate in the biennial Colloquium on Challenges in International Refugee Law. The colloquium, the eighth of which takes place next spring, brings 10 of the world’s most important lawyers and judges in the field to Ann Arbor for a weekend to mull a specific question and, afterward, to publish what are known as the Michigan Guidelines on the Protection of Refugees. Courts throughout the world cite them. The spring colloquium’s question focuses on how to interpret the 1951 U.N. Refugee Convention’s promise to refugees of “freedom of movement.”

H. Emad Ansari, ’10, MPP’15, JD’15, now a law professor in his native Lahore, Pakistan, recalls his own experience at the 2015 colloquium. “It was us studying refugee law in a classroom,” he says via Skype, “and then us talking in the same room with practitioners about what refugee law can become.”

In addition to teaching, Hathaway keeps up a busy travel schedule. In the past couple of years, he spoke in Japan, Germany, Malaysia, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Scandinavian countries and trained asylum judges in Ecuador and South Korea. In January, he heads to the Netherlands to accept an honorary doctorate from the University of Amsterdam.

Everywhere he goes, he preaches about his proposal to fix the world’s refugee system. He reminds the West, namely Europe and the United States, that their piece of the Syrian refugee wave is tiny compared with the millions who have alighted in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. Yet he also believes that the infrastructure, security, and humanitarian issues that arise from the Syrian migrant crisis may wake up the developed world to the fact that 10 countries, all poor, host 60 percent of the world’s refugees.

The solution Hathaway advocates, which he helped develop with a team of other experts, would centralize the decisions on destinations and definitions of refugees with the U.N. Commission on Human Rights. The approach would save wealthy nations the millions they spend assessing asylum matters in their court systems, freeing up money to administer this process. It also would require all signatories to accept a fair share of refugees. And refugees would no longer choose where they land, how long they stay, or where they permanently end up if they’re not able to return to their country of origin—even though refugee and state preferences would be taken into account under a preference-matching formula.

“We should be treating refugee law like an emergency room where we do triage and make sure people are safe rather than thinking about it as a convalescent home where we’re going to stay forever or for a long time,” Hathaway says. “The idea is to get people who are in trouble the remedy they need quickly.”

The U.N.’s decision to delay serious consideration of these matters, therefore, stung Hathaway. After the September meeting, he took to the U-M refugee program’s blog, RefLAW.org, to express his exasperation with the international community. Weeks later, he remained angry. “They turn refugees into penned-up animals,” he says. “I will keep trying to change that.”

Steve Friess is an Ann Arbor-based freelance journalist whose work appears regularly in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Playboy, BusinessWeek, and many others.