COVID’s Long Haul

•

Lead Photo by Leisa Thompson

PF Anderson, MILS’87, feels like they are on a roller coaster, but not the fun kind.

“Long COVID is what the doctors call a waxing/waning condition, and the patients describe that as a kind of corona-coaster, where you’re riding a roller coaster and that’s your COVID symptoms,” Anderson says. “You get better, you get worse. You get better, you get worse.”

Anderson, who uses they/them pronouns, got COVID-19 before they even knew it was COVID. Their first symptoms started on March 13, 2020, the day President Donald Trump declared a national emergency. Anderson hoped their symptoms would resolve after two weeks, but the illness continued to affect them.

“At the beginning, you think you’re starting to recover, and then you have a relapse, and your heart breaks,” Anderson says. “And this happens over and over, and after a while, you learn to stop hoping. You learn, even when you feel better, that it will happen again.”

Anderson has Long COVID, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least three months. For Anderson, fatigue is one of many persistent symptoms that continues to affect them.

“Before I got COVID, I was typically walking 7,000 to 12,000 steps a day. I walked everywhere. I was a martial artist. I was a dancer. I was very, very active physically,” Anderson says. “I get COVID, and it just plummets from 12,000 a day to 100. My functionality is at about half of what it was before.”

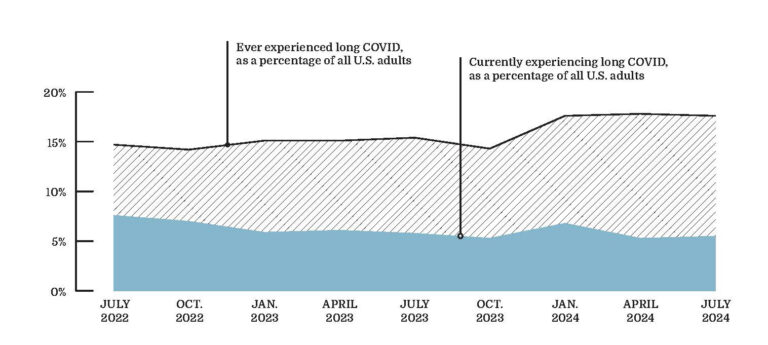

Estimates for how many people suffer from post-COVID conditions vary greatly and data is still emerging. Data from the Center for Disease Control’s Household Pulse Survey shows the prevalence of Long COVID among U.S. adults declined from 7.5 percent in June 2022 to 5.9 percent in January 2023, then increased to 6.8 percent in January 2024. In May 2024, 18.1 percent of U.S. adults reported ever experiencing Long COVID.

“It’s partly wishful thinking that people want to believe this can’t happen to them and that they will be immune,” Anderson says.

At the University of Michigan, the Post-COVID-19 Clinic provides care to adult patients experiencing prolonged symptoms following COVID-19. The clinic has treated more than 1,000 individual patients. Though researchers are still working to fully understand the illness, Michigan Medicine is helping improve the health and well-being of patients living with symptoms months or years after first getting COVID-19.

The Clinic

Michigan Medicine established its post-COVID clinic in April 2021 in the endocrinology department to treat patients experiencing lasting symptoms following COVID-19. Like other academic medical centers at the time, the early version of Michigan Medicine’s clinic included expert physicians from various specialties, from cardiologists to pulmonologists and beyond.

Dr. Katharine Seagly, co-director of the clinic, says that, like with many clinics of the time, much of the early research and tests “weren’t really showing anything” wrong, despite the patients’ prevalent symptoms.

“They know how to treat the things that they can find — but if they can’t find it, they don’t always know what to do,” Seagly says.

"We don’t have to have all the answers. It’s uncomfortable to move forward with uncertainty, but you don’t have to have all the answers to still help people.”

--Dr. Katharine Seagly, co-director of Michigan Medicine’s Post-COVID-19 Clinic

In December 2021, Michigan Medicine pivoted, creating a different model of care. The clinic transitioned to physical medicine and rehabilitation, focusing on the well-being of the whole person rather than specialized treatment for a particular organ system.

“In the face of not really having solid evidence for what was maintaining symptoms for many patients, the next logical step to continue to provide care for these patients, and to help improve their well-being and hopefully get them on a recovery trajectory, was to focus on improving function, even if we didn’t necessarily understand the etiology,” Seagly says.

Today, the clinic applies a biopsychosocial-ecological model of care, taking a wider look at the entire person to assess their health and well-being. This approach is unique, as providers assess each individual’s symptoms and create a customized care plan that considers the whole body, including potential underlying complications. “That’s really been a shift from the traditional medical model of care, which is just looking at medical tests and saying, ‘Here’s a pill to treat this thing that we can see on this blood test or imaging result,’” Seagly says. “Whereas biopsychosocial-ecological care really acknowledges that people are a lot more complex than that. It’s usually many factors that contribute to prolonged symptom experience.”

The Long Haul

Sometimes referred to as long haul COVID, the medical terminology is post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection or PASC. Michigan Medicine refers to any cluster of symptoms people may be experiencing after having contracted COVID-19 as post-COVID conditions.

According to the CDC, anyone can get PASC, including children and people who have had mild bouts of COVID-19 that did not initially require hospitalization. Each time a person is infected with COVID, there is a chance of developing PASC.

Common lingering symptoms may include fatigue, sleep challenges, brain fog, mental health and mood issues, headaches, dizziness, pain and tingling sensations, heart issues, taste and smell issues, and more.

“No patient has all the symptoms, and no one is alike,” says Krystal Martin, ’04, ’05, DPT’07, a physician’s assistant in the Post-COVID-19 clinic at Michigan Medicine.

Martin works with around 40 patients per week who experience a wide range of symptoms. Some patients even fell ill with COVID-19 in 2020 or 2021 and are just now finding their way to the clinic for support. She spends time with each patient, asking questions, listening, and trying to discover what other issues might be impacting their health.

“I’m like an investigator,” Martin says. “I’m looking for some of those underlying things that maybe the primary care [team] has not seen.” Even as research progresses, the medical condition proves hard to define.

“Nobody understands exactly what’s wrong. We have a lot of studies that have figured out what it isn’t, or at least have failed to find what it is,” Seagly says.

Small sample sizes, mixed results, or an inability to establish causality are several reasons why definite answers about the impact of COVID-19 on our health remain challenging, in addition to the fact that the disease is fairly new.

“It’s just an added layer of complexity that patients are navigating, practitioners are navigating, researchers are navigating, public health officials are navigating. … The global pandemic was unlike anything any currently living person has ever experienced before,” Seagly says.

In some cases, the patient’s symptoms are not overtly obvious. Symptoms like fatigue tend to be hidden and may be confused with other potential causes at first.

“We don’t have to have all the answers,” Seagly says. “It’s uncomfortable to move forward with uncertainty, but you don’t have to have all the answers to still help people.”

One of the key interventions the clinic uses is a post-COVID recovery group. Structured using a psychotherapy model, the six-week recovery group coaches patients suffering from symptoms on how to better engage in their own wellness.

“We use a lot of behavioral health strategies that we know are evidence-based and transdiagnostic. It doesn’t matter what the underlying disease is — we know that they help people improve their quality of life and increase function and participation in values-based activities,” Seagly says.

As COVID-19 and PASC research continues to develop, medical providers are helping patients move forward.

“Our society really puts importance on the bio aspects of the biopsychosocial model. And when those are less apparent, patients feel like they’re not being taken seriously,” Seagly says. “Our clinic tries to help patients see that we’re not ignoring that piece of the puzzle — that’s just the piece we know the least about. So, let’s put all of these other pieces in place in the interim, and regardless of whether or not that last piece ever falls into place, you’ll have made a lot of progress in your recovery.”

Holding Out Hope

Five years after the first case of COVID-19 was reported in China, COVID-19 continues to spread. The pandemic is still technically ongoing, but the World Health Organization announced an end to the Public Health Emergency of International Concern status in May 2023, meaning that the global crisis it caused has ended, but indicating that the disease is still a public health challenge.

The pandemic continues to be a topic of significant public and political debate in a way that is uncommon for other medical issues.

“Patients are navigating their symptom experience within the context of a very complex and sometimes hostile environment. … We see a lot of patients who feel invalidated and, to be honest, that only makes the symptoms worse,” Seagly says.

Patients often describe social pressure from family, friends, employers, or even primary care physicians who may doubt what they are experiencing.

“It impacts how patients perceive and process their symptoms. It impacts what sorts of interventions they may or may not be open to. It impacts how some providers approach them. Because of the politicization of the pandemic, it impacts the complexity of a patient’s recovery trajectory and experience of their post-COVID condition,” Seagly says.

With time, more solutions are sure to emerge, but they may not be straightforward.

“Post-COVID conditions are complex and nuanced, and every person’s experience is their own, and it’s different from the next person’s experience,” Seagly says.

“I think we will get to a point where we have more answers than we have now, but actually, there are very few fields in medicine and health care where we have absolute certainty. Expecting that is just setting ourselves up for disappointment,” she adds.

While there are still many unknowns about the lingering impact of COVID-19 on the human body, research and treatments continue.

“I tell patients there is hope. In our clinic, we really focus on the patient having a sense of control over their symptoms,” Martin says.

Nearly five years later, Anderson still struggles with debilitating symptoms. But even Anderson’s PASC experience is not all bleak.

“There is hope. … You can still keep recovering,” they say. “I’m at almost five years [post COVID-19] and they keep finding new things that work.”

Jessica Yurasek, ’04, is the senior director of communications for the Alumni Association of the University of Michigan.