As the Wolverines walk through the tunnel on their way into the Big House on football Saturdays, the players pass beneath a banner that some reach up to touch for good luck. It reads: “The team. The team. The team.”

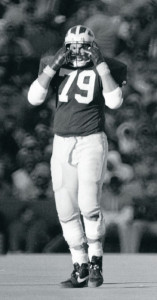

Warde Manuel remembers the first time he walked through that tunnel, as a freshman defensive tackle in 1986. “It was just an unbelievable experience, one I will never forget and one I’ll never take for granted,” he says. “When you’re around a team, you work hard for the benefit of your teammates.”

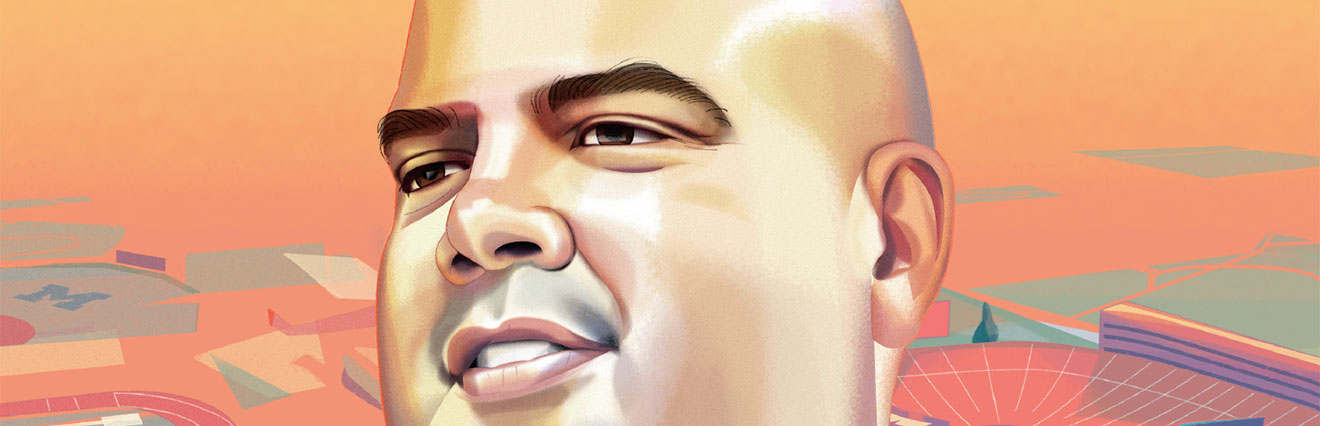

“He’s spent his entire professional life working toward this job.” — Nick Baumgardner, MLive, speaking about Warde Manuel

Manuel, ’90, MSW’93, MBA’05, a big guy with a young face, still looks like he could put on his pads and stride onto the field. But his playing days came to an abrupt end in 1989, when he suffered a neck injury that cost him his senior year and the life he expected to live.

“It was hard,” he admits. “There was a point when I was in tears, knowing my career here and my dream of playing professionally was going to end.” He could not have known it then, but the injury led him down a different path to athletic and administrative success.

In January, U-M President Mark Schlissel announced the appointment of Manuel as U-M’s new director of athletics. He succeeds interim athletic director Jim Hackett, ’77, and replaces Dave Brandon, ’74, who amped up Michigan’s marketing efforts, but became a lightning rod for criticism.

Manuel, who turned 48 in May, says his goals for the $153.6 million department are simple. He wants its athletes, male and female, to be successful both on the field of play and in the classroom.

“We are here, first and foremost, to have our students learn and grasp from the University of Michigan all the academic lessons you are taught to grow as young people,” Manuel says. “I want them to win, academically, to get the best grades and work hard and achieve great success in the classroom and graduate from Michigan.”

That ethic extends, of course, to athletic competition. “When we hit the field of play, or practice, I want them to want to be the best that they can be and the teams can be. We want to win championships, in the Big Ten, the national championships, for that was what was meaningful to me as well.”

Manuel returned to Michigan from the University of Connecticut, which won six NCAA championships during his three-year tenure as athletic director. UConn became the nation’s dominant power in women’s basketball and a perennial leader in men’s basketball, winning six NCAA championships.

He seemed like a natural pick, given his pedigree, and the hiring process went quickly from the time he was approached in December 2015 to the announcement of his appointment the following month. But there was plenty of competition. Michigan hired a search firm to consider 82 candidates for the job, including athletic personnel from major universities in the Big Ten and the Southeastern Conference. After all, Michigan athletic directors historically have remained in the job a decade or more. Fielding H. Yost, Fritz Crisler, and Don Canham all served for 20 years apiece. (See the sidebar below.)

“He was a top candidate from the beginning, no question,” says Nick Baumgardner, who covers Michigan athletics for MLive, a statewide media group. But Manuel “had to go through the same rigorous interview process everyone else did. And, if he wasn’t able to hold up against that process, the job would’ve gone to someone else.”

Baumgardner adds that Manuel’s status as an alumnus might have given him an edge, despite an already impressive resume.

“This isn’t just a guy who rolled through here as a football player 30 years ago and left with one degree. He has an MBA and a master’s in social work. He’s worked on a PhD in social work and psychology. And he became the first sitting athletic director hired by Michigan in its 150-year athletic history. He’s spent his entire professional life working toward this job.”

As much as Manuel is aligned professionally with Michigan, his personal roots are in New Orleans. He grew up in the Seventh Ward, attending Brother Martin High School, a rigorous all-boys Catholic academy. His father, now 81, worked three jobs, including as a waiter and a postal worker, while his late mother was an administrator in a middle school and for the New Orleans school system.

Although many young athletes there aim to land at Louisiana State University, his parents were impressed by both the athletic achievement and academic reputation at Michigan under head football coach Bo Schembechler. Manuel’s father, who had served in the U.S. Army, liked Schembechler’s no-nonsense style.

And his mother took a shine to him after the coach visited the Manuel household and ate her gumbo. When the meal was finished, Manuel recalls Schembechler saying, “’If Warde comes to Michigan, I hope he would share any of the gumbo that you would send.’ And my mom said, ‘Oh, Bo, I’ll send you gumbo any time.’”

She made good on her vow. During the fall of Manuel’s freshman year, a gallon of gumbo arrived at the Schembechlers’ home, and the coach invited Manuel and some of his teammates over to eat it. “It was very nice of him to share. He could certainly have eaten it by himself, but he had us over, and that was a memory I will never forget.”

Manuel says he’s determined to win national championships, but it’s not “win at all costs.”

Schembechler’s concern for him after his football-ending injury also stayed with Manuel, who says he strives to put the needs of his staff and players first. Manuel says he’s determined to win national championships, but it’s not “win at all costs.”

“I get my joy out of seeing the pride and the happiness in the students and the coaches and the staff who are working so hard,” Manuel says. “My joy is really not for me; it’s for them, to have that pride and that joy that comes with that sense of accomplishment.”

And while he respects the efforts of Michigan’s marketing staff, he doesn’t believe the University can simply rely on promotion to create its image. His approach is “allowing our success and the success of the University of Michigan to be the light that shines in terms of determining how Michigan is perceived in the greater world,” Manuel says. “We have a lot of great staff, faculty, and alumni who, by the work they do, market this school.”

One of Manuel’s biggest challenges will be in managing Michigan’s most-high profile football coach in decades, Jim Harbaugh, ’86, whose every quote and tweet seem to make headlines in the sports world. “Love it,” Manuel says, when asked about the vivacious coach.

But, Baumgardner says, Manuel already has had a few private words of guidance to Harbaugh, who, like everyone, needs an occasional reminder that he reports to someone.

“Harbaugh wants his boss to be a strong leader who has ideas and is willing to fight for them, just like he is with his football team,” Baumgardner says. “The best way to handle Harbaugh is to work with him. To engage in Harbaugh’s creative process and be willing to think outside the box, while also having the confidence to speak up when you don’t agree with something.”

Publicly, however, Manuel has Harbaugh’s back on the controversial topic of regional football camps. Michigan portrays them as a chance to teach skills to young athletes, but others see them as an effort to poach prospects from around the country.

Manuel takes issue with that: “Who has the right over territory? I came to the University of Michigan from New Orleans, LA. Nobody owns somebody in terms of where they can intend to play.” The NCAA, which initially banned the camps, later reversed its decision. As of press time, Michigan planned to conduct 38 such sessions in June, including one in Australia.

Manuel is equally impatient with people who thought it went too far in its splashy football signing day broadcast on Feb. 3. The event featured New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady, ’99, and baseball great Derek Jeter, who was offered a Michigan scholarship but decided to join the New York Yankees instead of attending college.

He says the telecast was a way of taking back the event from networks like ESPN, which have created programming around the young recruits. “What better way to introduce them to our fan base and the world than controlling the way of sharing our excitement?”

What about the expectations that the hoopla loads onto these players, who are barely old enough to vote? “Oh, as soon as you sign that letter of intent that says you are coming to Michigan, there are expectations,” Manuel says. “There are expectations they have for themselves, their family, this department, and our coaches.”

And, if Manuel has his way, his athletic descendants may some day walk under their own banners bearing the words that he would write for them: “Success. Success. Success.”

Michigan Athletic Directors

In 1898, Charles Baird became the University’s first athletic director. In the intervening years, a total of 12 men have served in that capacity. Here are a few notable athletic directors:

Fielding H. Yost, 1921-1941

- Coached Michigan football for 25 years, in addition to serving as athletic director.

- Was as popular in Ann Arbor as poet Robert Frost, who held appointments at U-M in the 1920s.

- Created the athletic campus, building Michigan Stadium, the golf course, the intramural athletics building, and the field house, now known as Yost Ice Arena.

FRITZ CRISLER, 1941-68

- Coached football for 10 years.

- Designed the winged football helmet.

- Was the namesake of Crisler Arena.

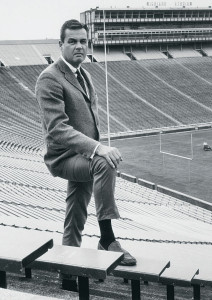

DON CANHAM, 1968-88

- Hired Bo Schembechler as head football coach on a handshake.

- Instituted marketing efforts to reverse dwindling attendance, which fell to 67,000 fans per game in 1967.

- Installed AstroTurf, leading announcer Bob Ufer to declare, “The hole that Yost dug, Crisler paid for, Canham carpeted, and Schembechler fills up every Saturday!”

BO SCHEMBECHLER 1988-90

- Served for two years as football coach and athletic director, despite pressure from the U-M board of regents to serve solely as athletic director.

- Remained as athletic director for a year after his retirement as football coach.

- Stepped down to join the Detroit Tigers.

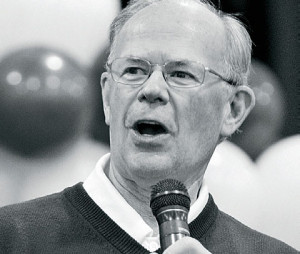

BILL MARTIN 2000-10

- Expanded the Big House, adding luxury suites and other amenities.

- Donated the first year of his salary back to the University.

Micheline Maynard is the senior editor of NPR’s “Here & Now,” the daily news program heard by 4 million listeners. She was Detroit bureau chief for The New York Times and a Knight-Wallace Fellow at Michigan in 1999-2000.