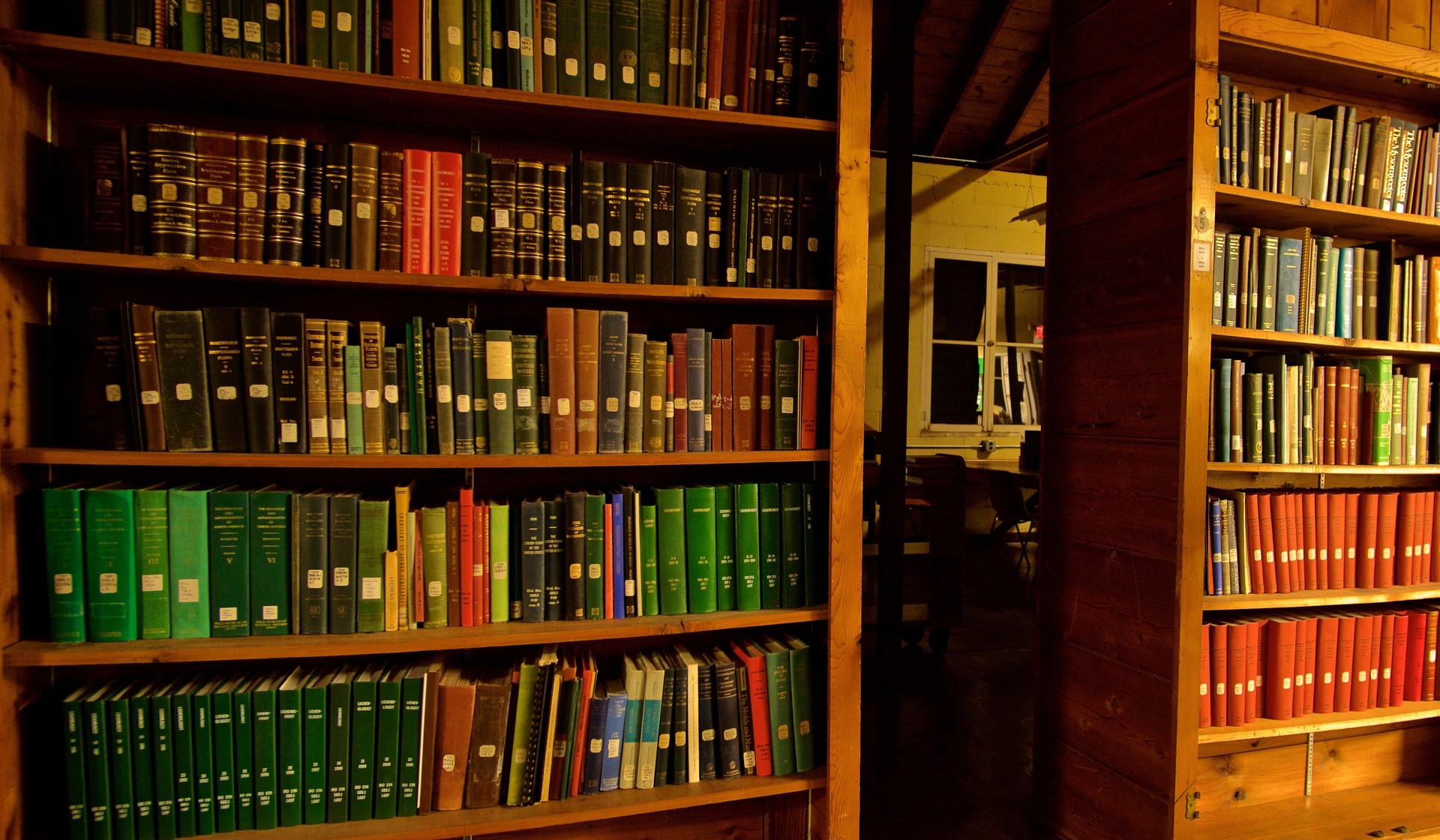

One of the most memorable traits of the two-story library at U-M’s Biological Station (UMBS) is its scent.

“The smell of the library encapsulates much of UMBS’s history,” says Jenny Kalejs, ’15, the UMBS recruitment and outreach coordinator. “You’ve got old books, containing a century of ecological research and discovery; traces of smoke from the woodstove on the main floor; and bits of detritus tracked in from patrons’ field boots.”

Since its founding in 1909, UMBS — part of LSA — has been a working research center during the spring and summer academic terms. Situated on 10,000 acres of land overlooking Douglas Lake in Pellston, Michigan, it brings students, faculty, and experts together to engage and learn about biology and environmental sciences, both in class and in the field. Not only do participants examine environmental changes, they also seek solutions to environmental problems.

It is a legacy dating back to the origins of UMBS. The University acquired the land from lumber barons, and the first researchers studied how land exploitation (the logging of trees and subsequent fires that cleared the property) affected the natural environment.

Beyond field, lab, and course work, the library — which is open 24 hours a day and houses roughly 18,000 books — is an important center for research.

“The library houses a working collection with a focus on natural history in Michigan and the Great Lakes region,” says Scott Martin, MSI’05, the UMBS librarian. “We have books on mammalogy, ecology, evolution, geology, and botany that all contextualize the region. You need these historic books to identify changes in species and ecology today. I don’t categorize myself as a hoarder, but I need a very good reason to take anything away.” He adds that exceptions include old print journals and out-of-date textbooks.

Martin says students and faculty often fill the library’s wooden tables and desks (the building has strong Wi-Fi), with one particularly coveted study spot being a nook upstairs with two wicker chairs and a large window overlooking the lake.

Given that the library has no heating beyond one small woodstove, one might wonder how the collection fares in the winter. “My preservation and conservation colleagues tell me the best way to prevent mold and insects — two problems you would have in northern Michigan — is for the building to freeze, as it has every year for decades,” says Martin.

While the pandemic closed the library in 2020, Martin looks forward to it being populated again. Though 75 students signed up to take fully remote UMBS courses during the month-long spring term that ends in mid-June, roughly 60 students are signed up for a hybrid summer term with 20 students at a time rotating through 12-day, in-person sessions in July and August. Additionally, many of the UMBS faculty (think microbiologists, ecologists, climatologists, geologists, and atmospheric scientists) plan to return, once again, with their families in tow to enjoy U-M’s northern campus.

“It is a wonderful place,” Martin says, “particularly when a breeze suddenly blows through one of the library’s lakeside windows.” Adds Kalejs, “The UMBS library inspires a sort of reverence for all the work that has been done here before.”

Jennifer Conlin, ’83, is the deputy editor of Michigan Alumnus.