Securing the Vote

•

Photo by LEVI HUTMACHER, MICHIGAN ENGINEERING

This story is part of a package of three democracy and voting articles published in the Fall 2024 issue of Michigan Alum. Click here to learn how U-M is preparing to support student voting and meet the alum who helps immigrants run for office.

J. Alex Halderman views theories about a “stolen” 2020 presidential election as something out of a novel or movie.

“I look at it really as science fiction. Which is interesting because science fiction always starts with some science fact — a little bit of real physics, a little bit of real possibility, and then just changes a few facts about the world,” he says. “To make science fiction credible, you need some scientific foundation. And that, unfortunately, is what the work of scientists like myself has been used for in this case of the 2020 election.”

Halderman is a professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Michigan, as well as the director of U-M’s Center for Computer Security and Society and Systems Laboratory. He is one of the nation’s foremost election security experts, having testified before Congress and authored numerous papers on the subject.

Halderman’s research is frequently taken out of context and used to support arguments that the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent, despite years of rigorous investigation that disprove alleged evidence.

“People who want to spread disinformation are going to try to do it regardless of anything that we can do as scientists,” Halderman says.

The core of Halderman’s election security research is aimed at identifying weaknesses in the system and helping shape improvements across the U.S. And while there was no evidence that there was anything wrong with the vote in 2020, he remains vigilant about concerns heading into this fall’s presidential election.

Casting Doubt

Voting security has always been a prevalent topic, especially in presidential election years. But it’s the public discourse surrounding the topic that has changed, Halderman says.

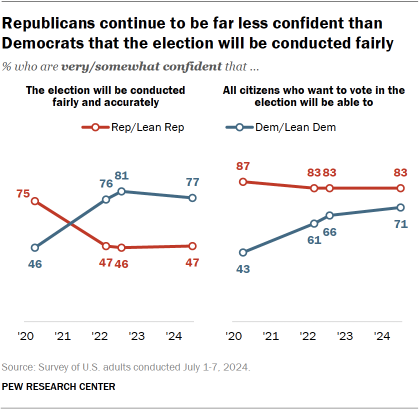

According to a July 2024 study from Pew Research, 77 percent of Democratic voters and 47 percent of Republican voters were “very” or “somewhat” confident that the 2024 election will be conducted fairly and accurately.

“I think what essentially everyone in the area did, both in government and in research and advocacy surrounding the topic, was we underestimated the threat of disinformation — that there would be attacks on the legitimacy of outcomes coming from people with domestic political interests,” he says.

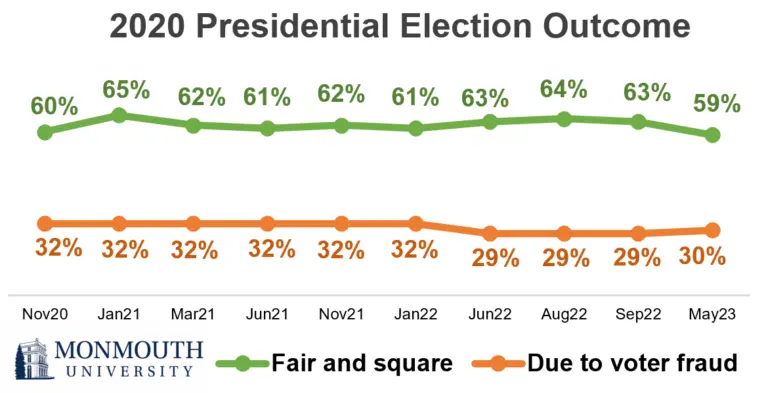

A 2023 Monmouth University poll found that 30 percent of Americans, including 68 percent of Republicans, believed that President Biden only won the presidency because of voter fraud.

Halderman has no qualms in speaking about the legitimacy of the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

“Despite years of scrutiny of the 2020 election, there is no good evidence whatsoever that the 2020 election in any state was stolen by technical means. There’s no good evidence whatsoever,” he says. “And it’s probably the most scrutinized election event in American history at this point, given the amount of public attention.”

The nuance in the conversation, Halderman says, is that there are real vulnerabilities in election systems.

“Yes, we need to be doing a better job as a country and as individual states and election organizations and preparing for attacks and security events,” he says. “But at the same time: no, there’s no good evidence that security problems altered in any way the outcome of the 2020 contest.”

A Vote of Confidence

Halderman is one of only a handful of election security researchers in the U.S. He works with government officials and agencies to offer solutions for everything from miscalibrated voting machines to faulty ballot anonymity algorithms. Ultimately, his research aims to identify and amend security risks before they can be taken advantage of by would-be hackers.

Electronic voting security improvements are continuously being made, but Halderman still has concerns about the 2024 presidential election, especially since it may be a close race.

“It looks like it’s going to be close. And that makes me extremely concerned because, although some states are well prepared, we’re, in fact, a patchwork of strengths and weaknesses still, going into 2024,” he says.

One of the best ways to keep election results secure, Halderman says, is to create a paper trail with hand-marked ballots that can be counted by a machine or by humans and audited, as is the process in Michigan. On the other end of the spectrum, one of the least secure methods of voting is online, where votes are tabulated in a database and can be digitally manipulated. Another potential security weakness, however, lies with ballot marking devices.

With ballot marking devices, voters enter their selections on a touch screen, and a ballot is printed with the voter’s selections filled in and a barcode that will reflect their choices when scanned. Or rather: should reflect their choices.

In 2021, Halderman demonstrated to a courtroom how he could gain administrative access to a ballot marking device within 30 seconds and change a ballot so the results generated by scanning the ballot’s barcode were different than what the voter selected, causing the votes to be counted for a different candidate than the voter expects.

That was part of an investigation into Georgia’s voting security specifically in relation to the 2020 election. The final report, which included Halderman’s research, concluded that “no evidence that any of the researcher’s proposed attacks, in whole or in part, have been attempted by any party in an election.” This conclusion was similarly reached in a separate investigation by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

“The mere fact that there were security risks doesn’t mean that anyone necessarily exploited those risks,” Halderman explains.

The company that makes the ballot marking devices, Dominion Voting Systems Corp., subsequently issued a software update to address these vulnerabilities. While states, including Michigan (which only offers ballot marking devices for accessibility accommodations), have installed the updated software, Georgia still has not.

“Fundamentally, that’s a question of resources, planning, and prioritization,” Halderman says. “If you’re going to operate a system that is subject to vulnerabilities like this, as a responsible public official, you need to price in and plan for keeping it up to date and patched.”

A judge could still order Georgia officials to update the systems before the election.

In the meantime, Halderman emphasizes that voters should actually be reassured by the investigations into the 2020 election, as each piece of reported evidence has been methodically debunked.

“The amount of scrutiny that’s happened with recounts, audits, and investigation of would-be attackers is much higher than any other election in American history with respect to cybersecurity and no good evidence has publicly emerged as a result of any of that, that the election result was wrong. It’s a stronger claim than merely that there is ‘no evidence,’” he says.

Moving Forward

There are things voters can do to support election security. Halderman’s first recommendation is to use a hand-marked paper ballot if one is available. His second is to encourage election officials to conduct a statistically rigorous audit.

“It’s our responsibility as citizens to be doing our part to ensure that elections are worthy of our trust.”

- J. Alex Halderman

“We know how to spot check rigorously election outcomes through what’s called a risk-limiting audit. That means you have people publicly inspect enough of the ballots to know that the outcome is almost certainly right. The closer the election, the more scrutiny you need to apply. But, in general, risk-limiting audits are a great way to establish affirmative evidence that that outcome was not affected by computer hacking.”

Halderman suggests performing these audits regularly would not only improve election security but also voter assurance.

“We need to normalize and depoliticize post-election audits. This is something that all states should just do as a matter of course, after every major election, in order to nip conspiracy theories and doubt in the bud, while also assuring everyone that the election outcome was not affected by computer-based fraud,” he says.

Halderman’s latest research includes risks and protections for voter privacy and robust methods for testing voting machine configurations, and he will continue to research election vulnerabilities in order to help make each election more secure than the last. He encourages voters to help in these efforts.

“Election security is something that needs [voters’] continued attention. It’s not a reason to panic. It’s certainly not a reason not to vote. But it should be an issue that voters continue to call on their public officials to attend to with the utmost diligence and care, and we need to keep providing more resources to election offices,” he says. “It’s too easy to forget about election mechanics and about this technology that’s fundamentally at the root of our democracy. But it’s our responsibility as citizens to be doing our part to ensure that elections are worthy of our trust.”

KATHERINE FIORILLO is the editor of Michigan Alum.