To walk through the Michigan Union on any given day is to see the University community in full throttle. Professors discuss research in the café, students head to club meetings on the fourth floor, and alumni attend a luncheon in the ballroom.

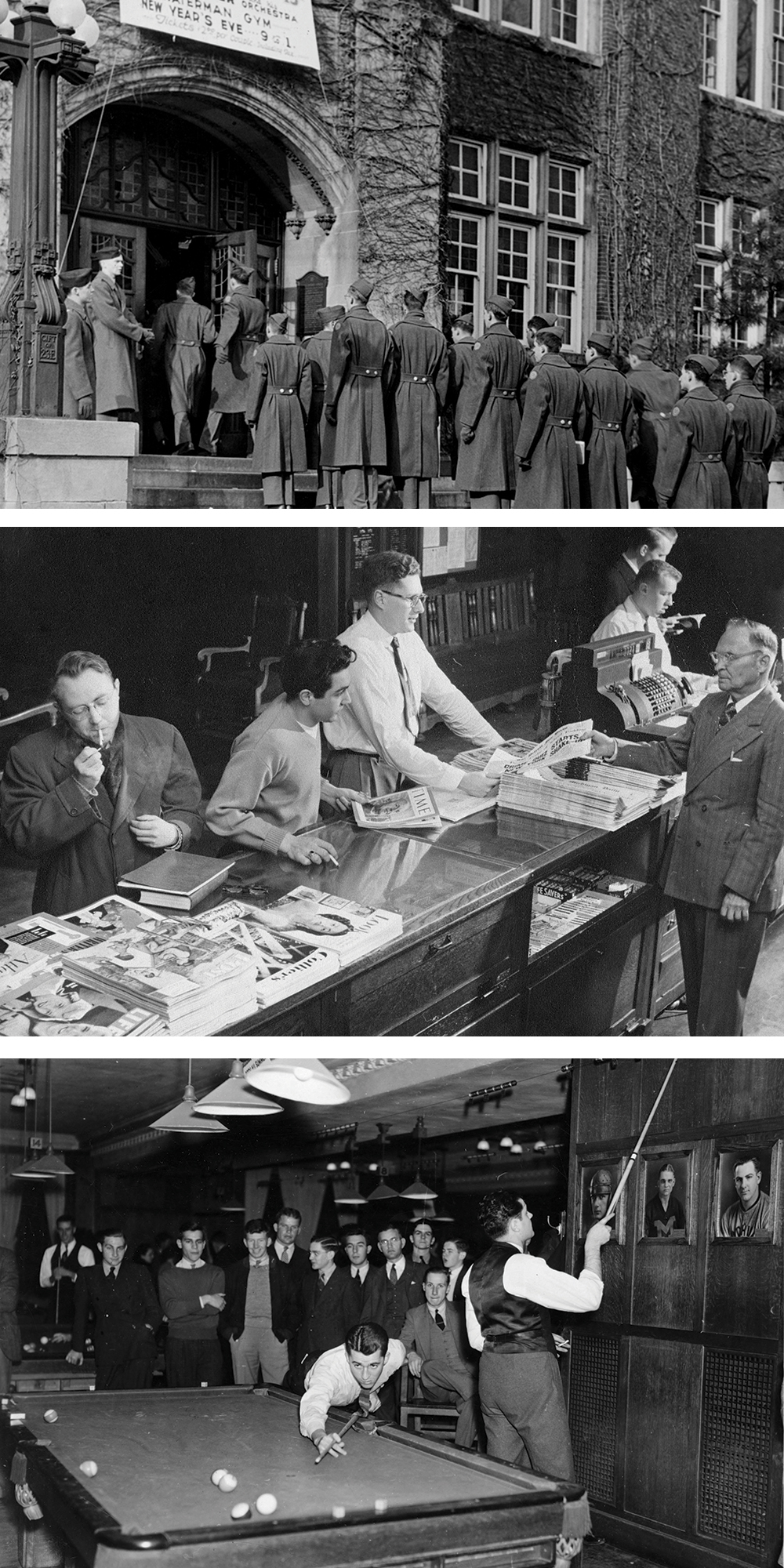

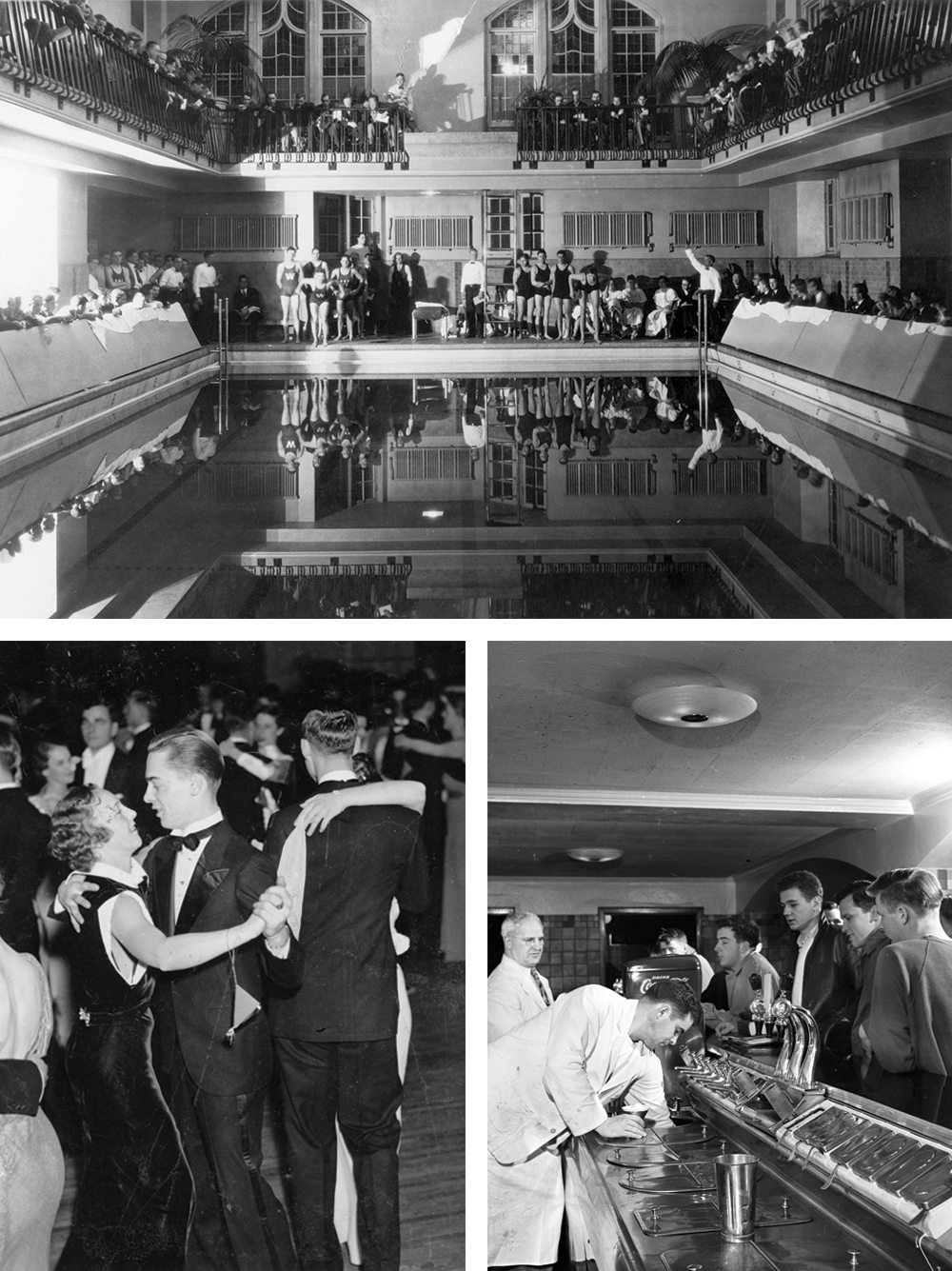

Now go back in history, say to the 1930s, and those same spaces would look different, but be equally busy. The café is the University Club, an elegant, two-story, faculty-only lounge and library. The student meeting rooms are alumni guest rooms. The ballroom—originally called the Assembly Hall—is the venue for an afternoon tea dance.

Often described as the University’s “living room,” the Union was formed in 1904 by student Edward “Bob” Parker, who imagined a unifying, democratic space for students, faculty, staff, and alumni. With no residence halls or other shared spaces, the only all-campus gatherings occurred at athletic events.

Since those early years, the Union has more than lived up to Parker’s ideal, serving as a town square on campus—a sort of indoor Diag with rooms of all sizes and amenities of all sorts—a common ground for people to convene and converse. Now on the verge of a major, $86 million renovation, the Union is about to usher in a new chapter, creating inclusive spaces for the future that will reflect enduring principles of the past, still inherent to the University community decades later. Though the Union began as a men’s club (see “The Forbidden Door” below), its original mission still resonates. Hanging on a wall in the basement of the building, the mission statement reads that the Union exists for “the primary purpose of enhancing the quality of campus life and favorably affecting the complete educational experience at the University of Michigan.”

To that end, the Union has always been about more than academia. It has been a space to discuss and engage in global challenges, progressive initiatives, cultural trends, and societal shifts. Through two world wars, the Union housed and fed soldiers and sailors in training. Then-Sen. John F. Kennedy announced the creation of the Peace Corps in 1960 on the steps of the Union, and two years later Martin Luther King Jr. chose a room there to discuss civil disobedience. Just over a decade after that, the nation’s first LGBT office, now called the Spectrum Center, was also established in the Union.

More than any other group on campus, the students have always been the biggest champions of its cause. In 1906, student minstrels sang to raise money for the Michigan Union’s first home (Cooley House). And in 2013, student leaders campaigned for the current building to be modernized—a project set to begin in May 2018.

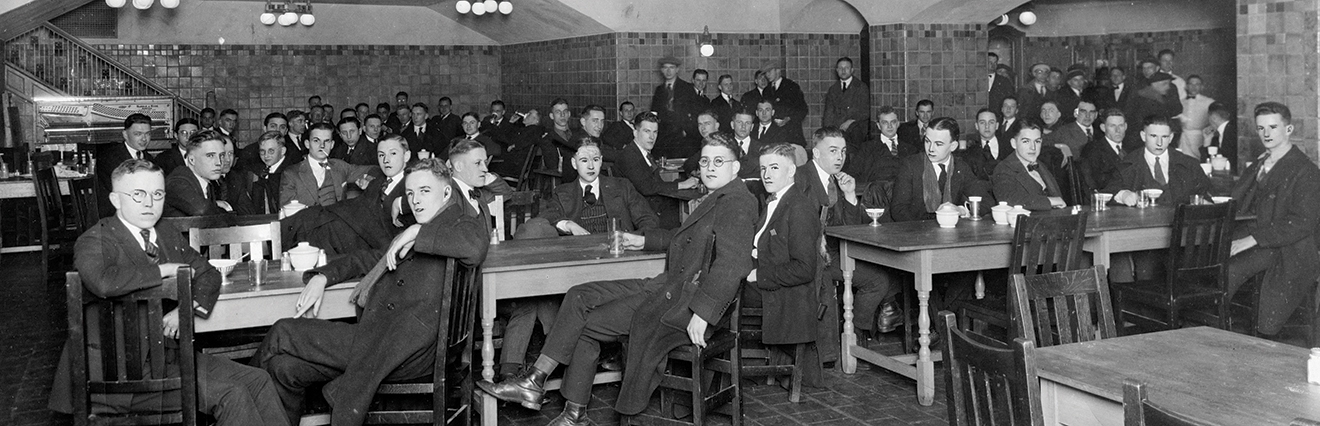

In turn, the campus community has benefited enormously. Jeffrey M. Rowe, ’93, writes in “The Michigan Union: 1904-2004, 100 Years of Student Life” how its creation had an instant effect on campus. “Almost immediately the Union established itself as the center of the University community,” he explains, citing early tallies of its usage. Records from the first academic year of operation (1920-21) show 1,437 meetings, dances, lunches, and dinners took place in the Union. The billiards room attracted 25,000 players and the bowling alley another 6,000. On the day of the Michigan-Chicago football game, an estimated 75,000 people came through its front doors to admire the roaring fireplaces, Tap Room, and barbershop.

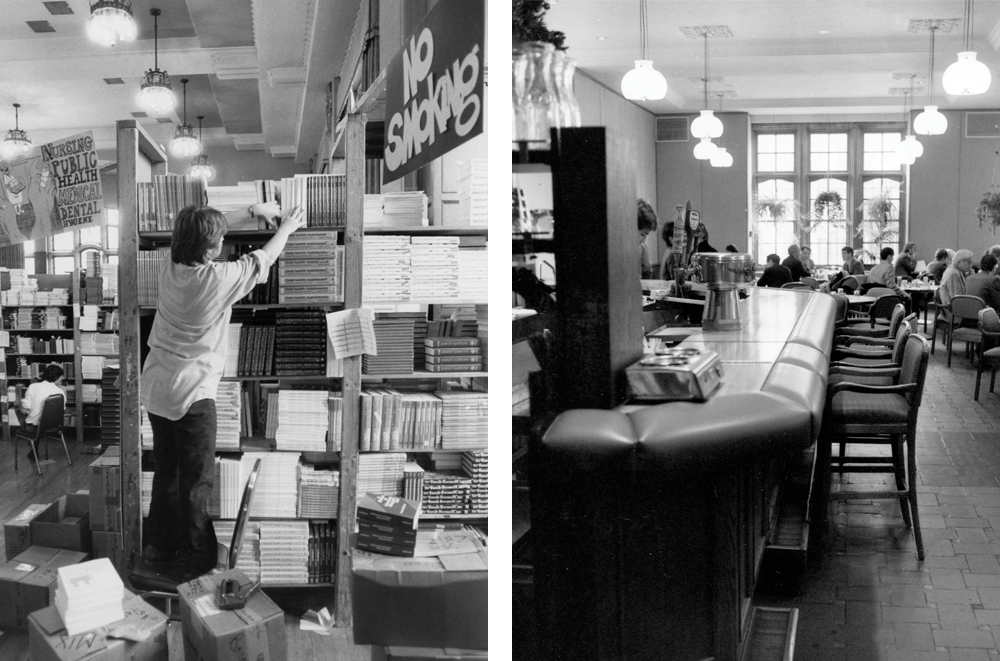

Today, while the guest rooms (later part of the Union Hotel) and the swimming pool (which opened in March 1925) are gone—along with a number of other recreational activities—the Union is still thriving.

Some 9,000 people visit the Union every day, whether to study, eat, or attend one of the 6,000 meetings or events that take place in the building annually, from concerts and lectures to dance marathons and movie nights.

Most impressive is how the original design of the Union, by Chicago-based architects and brothers Allen B., 1880, and Irving K. Pond, 1879, has held up over a century. In a Michigan Alumnus article published in 1920, one writer described the architecture as “Collegiate Gothic,” explaining that the design was meant to symbolize “the development of University education from its monastic origin to the modern time.”

With the 2018 renovation, the University hopes once again to bring the building into the “modern time,” while preserving its majesty, grace, and history. “We want to restore, repair, and refresh the Union,” says Loren Rullman, associate vice president for student life. “I like to think of it as a story arc. The purpose that existed at the very beginning—to create spaces and opportunities for people to understand each other—is the same purpose 100 years later. We want them to interact with people who are different from them. Then students are much more prepared to deal with the world or, frankly, to fix the world.”

In fact, it was the students who decided to fix the Union. In April 2013, two students from Building a Better Michigan (BBM)—a student organization formed in 2011 to advocate for improvements to U-M’s unions and recreation buildings—delivered a powerful presentation to the board of regents. “Today I come before you representing 17,000 LSA students that attend this University,” said Caroline Canning, ’13.

“I come before you representing the 96 percent of students who use the Union. We need to fix this building, where we come to work, play, study, lead, and live,” she added. “We need to provide the modern student with spaces that reflect our University’s institutions, values, spirits, and aspirations.”

Up next was fellow BBM student Louis Mirante, ’14. “Currently, students achieve in spite of, not because of, the spaces we have here,” Mirante said, adding that of the 1,400 student organizations on campus, only 40 have Union offices. Most are housed in small, converted hotel rooms.

The board of regents agreed with the students, thanks in large part to their willingness to help pay for the improvements with a $65-per-term student fee, the proceeds of which are also helping fund the renovation of other student-life building projects. (In 1919, the Union membership cost each male student $5 and was similarly built into tuition.)

The student fee—which includes a 20 percent allocation for financial aid to offset the costs for eligible students—covers more than half of the $86 million raised for the Union project. Of that designated sum, nearly half will go to much-needed infrastructure repair and restoration. (Outside masonry repairs have already been completed.) The remainder is for the construction of new interior spaces, designed to reflect the current needs of students and increase usability. To gather input, a study team led town hall meetings, listening sessions, surveys, and workshops involving more than 350 students, more than 500 alumni, and nearly 200 staff.

The plans include opening up the main-level lounge and restoring it to its original, more welcoming, size. The drawings also include the addition of a two-sided hearth, a place where the president of the University might give fireside chats. Also sketched out are plans to enclose the current courtyard with a glass roof to create a two-story, sunlit gathering-and-events space. An open plan “Idea Hub” is set for the second floor, creating co-working, inclusive spaces for student organizations and activities with the aim of people from different disciplines, faiths, and ethnicities engaging more.

Susan Pile, senior director of University Unions and Auxiliary Services, believes the community will feel an overwhelming gratitude toward the students who campaigned for the improvements when the building reopens in winter 2020. “This was truly a grassroots student movement,” she says.

“They called attention to their fellow students and said, ‘This building is integral to our experience. What happens in these spaces is part of our education. We need to fix the Union.’ And it resonated.”

The Forbidden Door

In early 1920, members of the newly built Michigan Union received copies of the House Rules. One of the rules—following the practice of traditional men’s clubs at the time—was that women could enter the building only through a side door.

What’s more, the only areas of the Union open to women at all times were the adjoining waiting room and the women’s dining room. Exceptions were made on dance nights, special occasions, and during brief windows of time, such as Saturdays and Sundays, when women could be escorted through all parts of the building, except the swimming pool.

One person incensed by this “stupid” rule was Margaret Towsley, ’28. Judy Towsley Rumelhart remembers her mother taking her and three of her sisters to the Union in the mid-1940s to board a bus for Detroit. The bus stop was located outside the Union, but upon learning the tickets were sold inside, Towsley took the most direct route with her offspring: through the front door. “We all followed her like little ducklings,” Rumelhart recalls. “We passed two guys coming out as we were going in, wondering what we were doing. They looked at us like we had just entered the men’s bathroom.”

Lee Price Arellano, ’57, MA’63, remembers her father dressing her as a boy and sneaking her through the door in the 1940s. “He took great delight having me dressed in long pants with my super curly hair confined under a cap,” she says. “He would take my hand and proudly walk up the steps and with a flourish wave me through the front door. We were never caught.”

These trespasses likely occurred after the death of Union door attendant George Johnson in 1946. Johnson faithfully guarded the front door against women for 26 years. When the University decided to eliminate his position, the no-women-through-the-front-door policy gradually relaxed.

In 1954, Suzanne Christy Collins, ’58, (on left in photo) was the first woman to cross the forbidden threshold officially. She was at the Michigan League when a photographer asked her and another woman if he could photograph them walking through the front door of the Union. As a newly arrived freshman, Collins says, “It was pretty exciting.” However, the opportunity existed not because the rule was changed but because a remodeling project had closed the side entrance.

While the rule officially changed in 1956, it was a year too late for Ruth “Terry” Meury, ’53. Meury worked at the Union all through junior high, high school, and for five years as a college student. “When I was married in June of 1955, I was not allowed to use the front door, even though my wedding dinner was held there.”

Two other restrictions, however, took longer to undo. It was not until 1968 that the rule forbidding women from using the billiards room unaccompanied by a man was abolished. Four years later, the last barrier was revoked prohibiting women from becoming life members of the Michigan Union.

Steve Rosoff, MA’87, is an Ann Arbor-based freelance writer who spent almost two decades writing copy for the J. Peterman catalog.

Jennifer Conlin, ’83, is the deputy editor of Michigan Alumnus magazine.