For more than 40 years, Holocaust survivor Irene Butter chose not to share her experiences in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where she overlapped for a period with Anne Frank. When Butter moved to the U.S. from Algeria in 1945 at age 15 — joined six months later by her mother and brother, who arrived from Switzerland — she did not discuss the horrors they experienced.

“Our well-meaning relatives told us to forget the past and never to speak about it again,” Butter recalls, adding it was “a message received by many survivors at that time.”

Then in the 1980s, she heard these words from a prominent Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel: “If you were in the camps, if you smelled the air and you heard the silence of the dead, then it’s your responsibility to be a witness, to provide testimony, and to tell your story.” His words made a deep impression on Butter, by then a professor at U-M’s School of Public Health, where she taught from 1962 to 1996.

“I decided that being a witness was going to be my responsibility.”

In 1976, she gave her first presentation at her daughter’s school. Since then, she has channeled her energies into raising awareness about the Holocaust, giving presentations at hundreds of schools and, in 1990, co-founding U-M’s Wallenberg Medal and Lecture. The event honors Raoul Wallenberg, ’35, a Swedish diplomat who rescued tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest, Hungary, during the closing months of World War II.

To this day, the Wallenberg Medal is awarded to humanitarians whose actions on behalf of the oppressed reflect his sacrifice. “I always felt I needed to do something like this to acknowledge the gift of being a survivor of the Holocaust,” Butter says. The first Wallenberg recipient was Elie Wiesel.

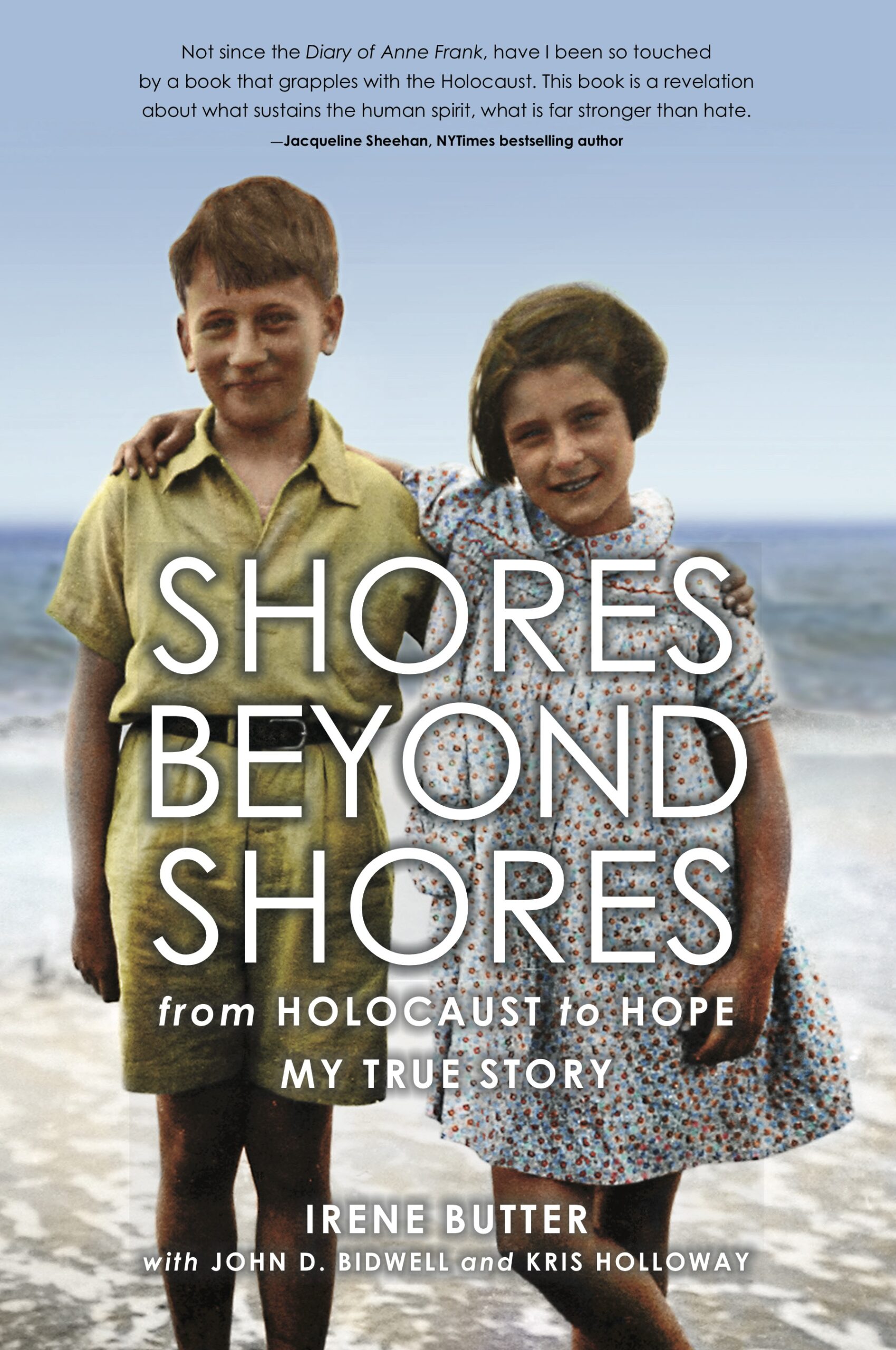

According to the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, 85,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors are currently alive in the U.S.; the youngest survivors are 75 years old. On Dec. 11, Butter turned 90. As survivors continue to die, she wanted to ensure there is a written record of her experience. To that end, she wrote “Shores Beyond Shores: from Holocaust to Hope, My True Story” (TSB, 2019).

Her book documents in precise detail her journey from a comfortable existence as a Jew living with her parents, brother, and grandparents in Berlin to her family fleeing persecution in 1937 to Amsterdam, leaving her grandparents behind. (They later died in the concentration camp Theresienstadt.) Six years later, her family was first sent to Westerbork, a transit camp in Holland, and then to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp when Butter was 12 years old.

While imprisoned there, she crossed paths with Anne Frank. Though she had not known her in Amsterdam, they lived in the same neighborhood and shared a mutual friend. “The friend would often tell stories about her because she was such an animated person,” Butter recalls.

At Bergen-Belsen, Butter and a friend of the Franks met Anne, who was then 16, at a barbwire fence that separated the women’s adjoining sections. “She was very thin and very pale, and she didn’t have clothing. She had a gray blanket wrapped around her,” remembers Butter. Frank asked her friend if they could get her some clothing. Butter and the friend gathered some and threw it over the fence, only to have someone quickly steal the bundle. Butter left the camp shortly after in 1945. “There was typhus all over. My guess is Anne died in late January or early February of 1945.”

Butter’s family was able to leave Bergen-Belsen for Switzerland as part of a prisoner exchange program for Jews who had passports to South American countries, which her father had obtained. Consuls in a number of European countries issued passports, even though they were not valid, in an attempt to save Jews. Germany had a foreign policy that intended to exchange Jews for German prisoners of war and German civilians who had immigrated to the Americas earlier in the 20th century. The exchange policy was meant to return human resources to Germany to help win the war, but it is unclear if that ever happened. All told, 103 people were allowed to leave Bergen-Belsen, mostly with South American passports. “It’s miraculous we were part of it,” Butter says.

En route to Switzerland, Butter’s father died. Because her mother and brother were too ill to travel, they were allowed to remain in Switzerland, while Butter was sent to Algeria. Eighteen months later, in 1946, the family reunited in the U.S. and moved to New York City. Butter says she then decided to try to “find a wonderful life like I’d had before.”

Butter’s book comes at a time of a rise in antisemitism. According to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the American Jewish community experienced the highest level ever of antisemitic incidents in 2018. The ADL began tracking incidents in 1979. Since then, more than 2,100 acts of assault, vandalism, and harassment have been reported across the United States. Butter sees parallels between the time leading up to the Holocaust and today’s environment, with certain groups targeted, alongside a rise in white supremacy and anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Butter’s former student Kris Holloway, MPH’96, encouraged her to write her memoir. The two became close in 1993, when Holloway found it challenging to head back to class just three weeks after giving birth to her first child. Butter, who was her adviser, refused to let her drop out and offered to babysit regularly.

Holloway and her husband, John Bidwell, had long broached the subject of Butter writing a book. In 2013, she agreed to let the couple co-author her memoir.

Says Butter of the experience, “It brought back memories I didn’t know I even had.”

Butter did indeed find the wonderful life she sought in the U.S. She met her husband, Charles Butter, at Duke University, where they were both graduate students. She married him in 1957 and three years later earned her Ph.D. in economics. In 1962, she and her husband, a psychology professor, moved to Ann Arbor to work at the University, where each is now a professor emeritus. The couple has two children, three grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

Butter hopes to encourage young people to become social activists “to trust their own values, rather than be persuaded by what other people think.” Not being a bystander to injustice is paramount, she says. “If we could practice that on a large scale, I think we’d have a better world.”

A Haunting Hunger

In her memoir “Shores Beyond Shores: from Holocaust to Hope, My True Story,” survivor Irene Butter vividly describes the struggles she faced in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where she also encountered Anne Frank. Since 1976, Butter has been telling her story at hundreds of schools to raise awareness about the Holocaust. It took five years to write her memoir. Following is a short excerpt.

“At first, hunger was a pesky neighbor, sometimes noisy at night, interrupting sleep. Then it was a nagging visitor who came rapping on the door more and more. Finally, it had the keys. Hunger marched in and settled down. As the spring months dragged on and the cold raced across the camp, through every crevasse, under every blanket, hunger went from a distant stranger to an annoying acquaintance to a constant companion. There was no place to escape, no room to retire to. It became an ever-present, day-after-day rumbling.”

Julie Halpert, ’84, is a freelance journalist for many national publications. She is a regular contributor to The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. She also co-teaches journalism in U-M’s Program in the Environment.