My family has long had an affection for The Michigan Daily, as my mother and her two brothers had all been reporters on The Daily staff while attending the University of Michigan in the years just prior to World War II. Curiously, I knew very few other details of this family experience, except that my uncle, Carl Petersen, had been the managing editor of The Daily in 1940, and that he had died in Germany in 1945, in the last days of the war.

Looking for more information (and with plenty of time on my hands as a recently retired U-M professor), I decided to visit the Student Publications building, the same building where Carl would have had an office more than 80 years earlier, looking for perhaps a few more details about his experience.

What I found was a story which became more tragic, yet more fascinating, the more I uncovered.

I quickly learned that there existed a Carl Petersen and Mel Fineberg Scholarship for promising Daily journalists, to honor the two Daily staff members killed in World War II. I found a beautiful wood-paneled conference room, evidently a hub of The Daily’s activity, named after my uncle.

More investigation, using the excellent and recently redone Daily digital archives, allowed me to put together Carl’s editorial take on the swirling pre-war events, which included some very energetic back-and-forth communications between Carl and several prominent U-M professors — not all of them complimentary.

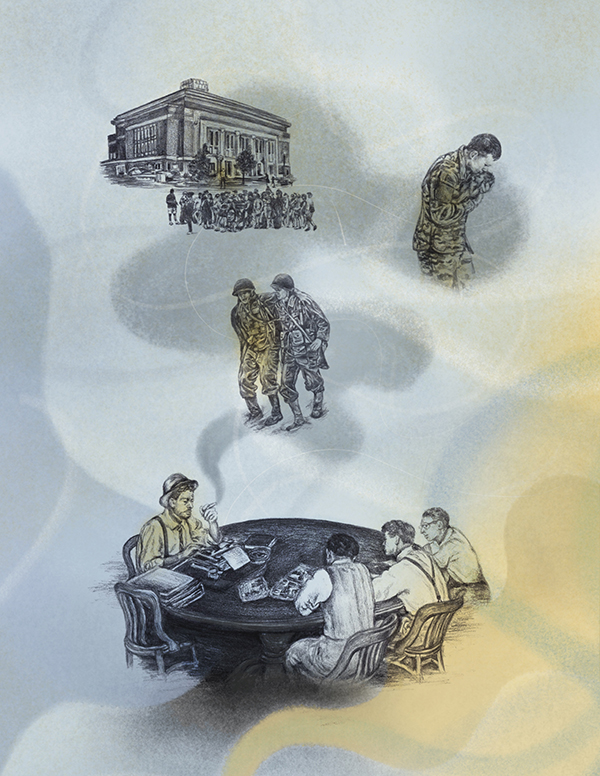

A tall, skinny, and gregarious person, Carl was sometimes referred to by colleagues at The Daily as a “vibrating broomstick,” referencing his thin frame and boundless energy. From his editorial position, Carl supported an isolationist plan that saw Europe settling its disputes overseas before direct U.S. intervention, advocating instead a plan to use the vast American resources for post-war reconstruction. In one momentous rally on the U-M campus, Carl gave the keynote anti-war address on the steps of Hill Auditorium, attended by more than 3,000 enthusiastic U-M students and faculty.

Although Carl was an isolationist, his younger brother Pat, a freshman at U-M and also on The Daily staff, felt differently, and entered a campus Navy program designed to train new pilots. He died on his first solo flight at Selfridge Air Force Base, at age 19.

Although Carl was an isolationist, his younger brother Pat, a freshman at U-M and also on The Daily staff, felt differently, and entered a campus Navy program designed to train new pilots. He died on his first solo flight at Selfridge Air Force Base, at age 19.

When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, circumstances changed immediately, including Carl’s philosophy. He faced four choices: ask a famous uncle, then the president of General Motors and head of the War Production Board, to provide him a safe administrative job; continue on as a noncombatant war reporter for The Associated Press; apply for the “sole surviving son” policy, exempting him from military service after his brother’s death; or the fourth (and most unpopular with his family) option, which was to immediately enlist in the Army infantry, insisting that he be assigned as a combatant in the field.

Carl soon left for the Army’s officer training school and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the infantry. While training in a remote Army base in Wyoming, he met his wife, Donnie, and they had their son, Pete.

Carl was deployed overseas in early 1945, leading his infantry team as a second lieutenant, operating near Düsseldorf, Germany, in the final weeks of the war. He wrote Donnie love letters constantly, expressing the importance of duty to his country, but also, understandably, his ardent desire to get home. He had last seen his son Pete as a newborn baby.

On May 1, 1945, one week before the formal end of World War II and just two days after his last letter to Donnie, Carl volunteered to lead a night patrol aimed at flushing out recalcitrant Germans from a nearby position. He and three others ran into small arms gunfire, and Carl sustained a fatal gunshot wound to the head.

I later presented this story to the collective Daily staff during their annual awards ceremony, and presented the Petersen and Fineberg Scholarship award to two very promising Daily reporters. But more than attaching an unfamiliar name to a monetary award, this time I was able to put considerable detail into Carl’s gut-wrenching story, which I know made a big impact on the awardees.

Carl’s story was largely unknown to his son, in addition to so many of my siblings, grandkids, and their cousins, all of whom will perhaps now have an even greater appreciation for their family’s U-M legacy.

After I made my awards day presentation, I managed to slip into the second-floor Daily staff room, and, with some help, found my way to what would have been Carl’s office, complete with well-worn armchairs (probably the same as was in use at that time), with desks for various associate editors as well. I imagined the serious discussions taking place in a smoke-filled room, but also the comic relief that I learned was a constant feature of Carl’s outgoing personality. I left feeling that had it not been for the tragedy of the war, mixed with Carl’s sense of duty and courage, my uncle would have gone on to be a fantastic father, a nationally prominent journalist, and, of course, an enthusiastic lifelong Wolverine.

Darrell A. Campbell Jr., MDRES’78, is a professor emeritus of transplant surgery at U-M.