The voice on the answering machine was steady and measured: “This is grandmother. Grandfather and I will be there at 4 p.m.” She was rather formal in person, and the telephone seemed to make her more so.

My roommate laughed, “You have the most dignified grandparents.”

“I know,” I said. “Please, please, please, make your bed and hide the junk somewhere before they get here.”

I was anything but dignified — a messy, harried student in my first year at U-M and overwhelmed with a million things. I loved Ann Arbor and was doing my best to sample everything it had to offer. In the previous 24 hours, I’d been to Stucchi’s twice for ice cream in lieu of an actual meal, trimmed my own hair, gone to an informational meeting about performing in “The Big Show” (an improv comedy performance), called my parents for money, been to a party at West Quad, met up with friends at Dooley’s, and gotten about four hours of sleep.

On that particular afternoon, my grandparents’ visit was feeling more like a responsibility than a treat. Their pace was not my pace. Unlike me, they moved and talked calmly. In their middle 70s, they had figured out decades and decades ago that you could smell the roses one at a time, rather than tripping over yourself headfirst into the rosebush.

Michigan alums themselves, they lived only an hour away and liked to visit. They had only two grandchildren, and, for most of our lives, my sister and I had lived in another state. So it was a treat to have a granddaughter so close for a change. But at that moment, when I had a test to study for and a writing assignment due the next day, getting close with them wasn’t high on my priority list. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to see them; I just had so much to do.

I raced over to the UGLi with my books, desperate to make a little headway before they arrived. A few study breaks later, I found myself light on progress and having to run back to the dorm to be dressed in time. I threw on a random sweater and skirt.

There was a knock on the door: 3:59 p.m.

I shoved my bathroom caddy into the closet.

“Cheryl?”

I swept the contents of my desk into my book bag, pulled the comforter over the tangle of sheets on my bed, and then did the same with my roommate’s. I had just seconds until …

… a second knock.

I threw the dirty dishes into the mini-refrigerator and kicked my wet towel under the bed. I opened the door.

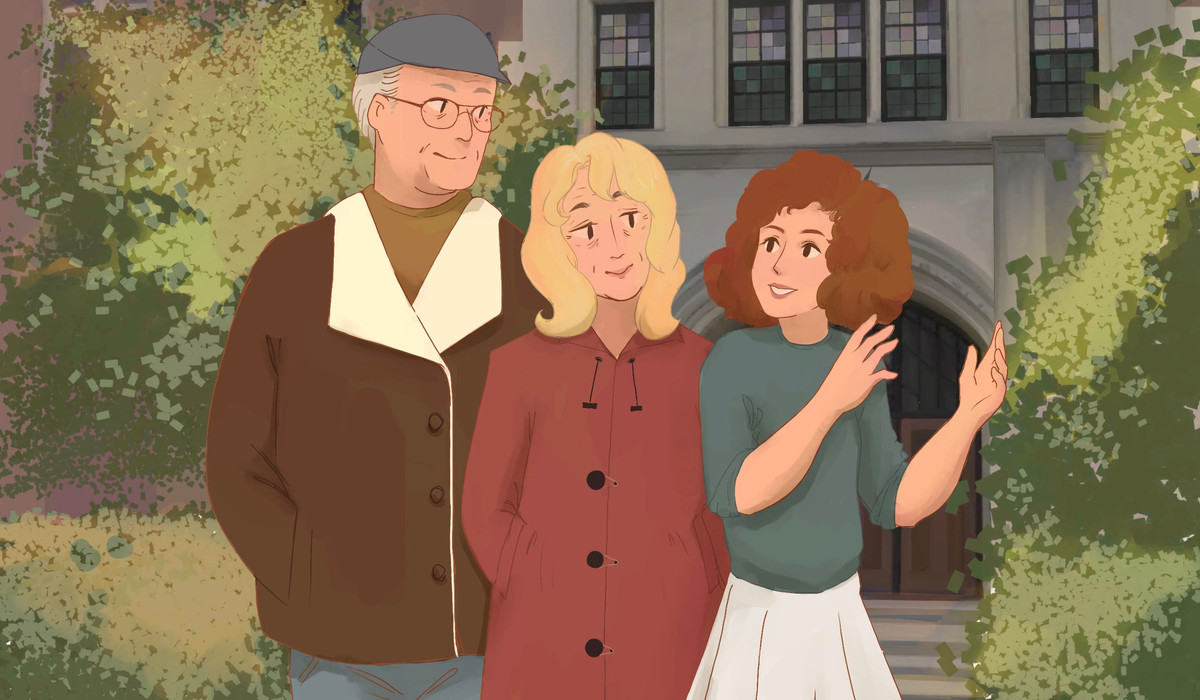

Natty as ever, my grandfather in his wool cap and my grandmother in her stylish raincoat hugged me, surveyed the room, and handed me a wicker tray of fruit.

“Shall we go?” I asked as if I’d been sitting around all afternoon waiting for them. I didn’t need them inspecting anything too closely. Plus, the sooner we left, the sooner I’d get to eat. They liked the Gandy Dancer and Weber’s, but what they loved was the Old German.

I ate a massive portion of beef rouladen with spaetzle as they marveled. “You just don’t know how bad the dorm food is,” I assured them and proceeded to describe my basic food groups as cereal, jello, and fries. I was certain to get even more fresh fruit the next time.

After our early dinner, we drove back to campus, a harrowing experience as I managed to get my grandfather to turn the wrong way down a one-way street not once, but twice. It would later become a bit of a joke between us. As a pedestrian, I could walk the sidewalks any direction I pleased. With time, I got better about not sending him into oncoming traffic and he got better at looking for himself before taking my direction.

We parked. My grandparents were spry and up for a walk around campus. Unlike my parents, also alumni, they didn’t point out every landmark from their days in Ann Arbor. They asked me questions and let me ramble on and on about everything going on in my life. They’d have been perfectly justified in talking away. My grandmother, a sharp woman with a bachelor’s degree, had learned flower arranging at Michigan from the visiting Japanese imperial court florist while my grandfather pursued his master’s degree in geography. I would ask them about it in the years to come, but on this day, they were content to simply walk and learn about me.

“We should head back before it gets dark,” my grandfather finally said.

“You let us know when you’d like us to visit again,” said my grandmother.

“You can come anytime,” I blurted. I didn’t want them to leave. I’d been hassled by their arrival, but then I didn’t want them to go. They were kin, a concept I was grasping deeply for the first time. As I raced about trying to find my place at Michigan, I had right in front of me the people to whom I would always belong. I hugged them tight, and when they drove away, I cried. We were the same. They had come to Ann Arbor many years ago. A couple decades later, my parents had. Now it was my turn. And they understood.

Cheryl McPhilimy, ’91, is principal and founder of McPhilimy Associates, a communications and strategy consulting firm in Chicago.