Life Under Curfew

•

Karen Potts, ’64, was a first-year student who was eager to see then-Sen. John F. Kennedy the night he visited U-M during the 1960 presidential campaign. She and her date had found a good spot inside the Michigan Union where they could see and hear him through a window. But Kennedy was late. Very late. That wasn’t a problem for Potts’ date, but it was for her because the clock kept ticking ever closer to the women’s curfew.

Yes, in 1960, women at the University had a curfew.

Kennedy finally arrived after midnight on Oct. 14, and Potts did get to hear him. But she wasn’t able to stick around after his famous speech to try and get a closer look or shake his hand. Instead, she had to race across campus to get back to Stockwell Hall before the doors were locked.

“It was well past curfew, but women were able to stay there waiting because they kept announcing, over loudspeakers, that they were adding another half hour to the curfew,” Potts says. “We finally got to see him—well, I just saw the back of his head—but once he was through speaking, they didn’t extend curfew anymore. I remember running up the Hill to get to the dorm in time. I did make it.”

It has been 60 years since the University started to phase out the curfew, which wasn’t uncommon for women on college campuses in the 1960s. Plenty of schools— including Purdue University, the University of Nebraska, the University of Florida, the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and others—had curfews. Editions of The Michigan Daily from 1964 reference the curfew as midnight on weekdays and 1 a.m. or 1:30 a.m. on weekends, although many women interviewed for this article remember them earlier—10 p.m. on weekdays and midnight on weekends.

According to the Bentley Historical Library, it’s likely U-M’s formal curfew policy was implemented when Myra Jordan became dean of women in 1902. She began the League House system of coordinated boarding houses and instituted the policy of “in loco parentis,” which included a number of rules for women, voted on by the Women’s Judiciary Council.

While some female students took curfews in stride, others were seriously annoyed by it.

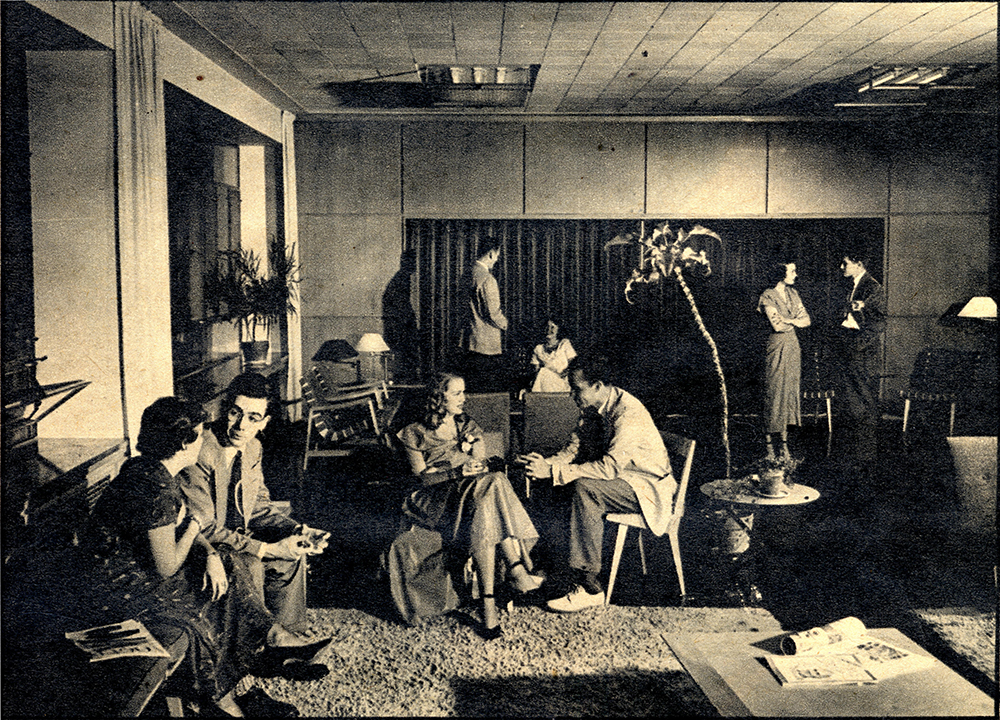

Photo courtesy of the U-M Bentley Historical Library

“It was incredibly irritating. I had more freedom in high school,” says Judith Murray Rollenhagen, ’70. “But nobody really fought it because those were the rules. It felt like tradition, so you just didn’t question it.”

Letty Silverberg, ’68, also remembers thinking how unfair the curfew was but being unable to do anything about it. “At that time, it was how women were treated. It was to protect you, they would say. It wasn’t the age of rebellion just yet. It didn’t cross our minds to do anything. We didn’t argue with authority. We were used to men doing one thing and women doing another.”

There were rules that went along with the curfew, enforced by housemothers who lived in dorms and sorority houses and stood guard at front doors as each night’s deadline neared so they could lock the front door. Women had to sign record books before leaving their residence hall or sorority at night, and they had to sign back in when they returned to show they made curfew. Some recall lenient housemothers, but others say rules were strictly enforced. Those who did not make it inside in time faced penalties, including staying in for extra time on weekends. If it happened too many times, they had to appear before the Women’s Judiciary Council.

The pressure to arrive in time resulted in many close calls as women raced across campus to make it home from movie theaters, parties, and other activities. Others, however, found a way around the rules. “You had to sign out and in, but the girls who didn’t want to do that simply didn’t sign out when they left at night,” Potts says. “It was that simple.”

Helen Hill, ’68, admits that she found a way around the curfew a few times when she and a friend decided to work late in a lab—as the male students were allowed to do before a big test.

“We didn’t like sneaking around in the dark. It was before there were lots of lights, so it was a little risky,” Hill says. “But we would wind up leaving the lab at like 2 in the morning because we wanted to study there, too. We would have to sneak back through campus, trying to avoid campus police. If they saw you, they wouldn’t have arrested you, but they would take you back to where you lived and get you in trouble with your housemother.”

Making a successful end run around the police on those few nights, Hill was able to sneak back into Henderson House, where she currently serves as chair of the board of governors. “When we got back to Henderson House, the door would be locked. But at that time, we had pingpong tables in the basement covered with typewriters, and that’s where people would work on term papers late into the night,” Hill says. “The windows were big, so when you knocked, somebody would let you in and you could slide inside. Meanwhile, the men could just go back to their dorms whenever they wanted to.”

For those who did return in time, curfew made for some crazy scenes in front of residence halls and sorority houses each night. “I just remember the long line of all of us outside Alice Lloyd as curfew approached,” says Silverberg. “Everyone was lined up kissing their boyfriends. The poor housemother had to stand at the door watching it all and waiting for it to end every night.”

Photo courtesy of the U-M Bentley Historical Library

In 1962, the curfew began to phase out, first being abolished for senior women. Rollenhagen remembers when that happened at her sorority house; seniors were given keys to come and go as they pleased. Younger women, including Rollenhagen, found that opened a door for them, too.

“You just had to make sure if you were going to be out late, that you were with a senior who had a key so you could always get in,” she explains with a laugh.

Curfews were abolished, bit by bit, throughout the 1960s. By 1968, the U-M board of regents decided to remove the curfew for women for one trial semester if parents sent a permission slip requesting it, which 86% did. In 1970, they officially abolished mandatory curfews in residence halls.

“That felt like real freedom once you had no curfew,” says Rollenhagen.

“I think it’s important to share these stories so everyone knows how far we’ve come and what other people have gone through,” Hill says. “There’s more progress to be made even today for women, but it’s just amazing how much change there has been in our lifetimes. When you talk to younger people, they almost always say, ‘You can’t really mean it. That didn’t really happen.’ But all of these things really did happen, and it wasn’t that long ago.”

Jennifer Davis, ’95, is a writer and communications coach who runs her own company, Jennifer Davis Media Group, based in Washington, D.C.

The Old Days

The curfew wasn’t the only policy that made life on the U-M campus quite different in the past. Three alumni share their recollections of just a few.

No Women Allowed

Women were not granted full and equal access to the Michigan Union until 1968. For many years, women were allowed in only through a side door and when escorted by a man.

Judith Murray Rollenhagen, ’70, remembers when things changed.

“My dad went to Michigan 30 years before me. I remember so clearly when he came to visit and we could finally walk up the front steps and into the Union together. He was so proud.”

The Marching Men of Michigan

The U-M Marching Band was all-male until 1972, when several women auditioned and 10 made it. Before that, the head of the band, George Cavender, was quoted in the Daily as saying, “It’s more violent physical activity than would be proper for a lady.”

Helen L. Hill, ’68, remembers how disheartening that was for many women, including a roommate named Chris who was a talented musician and got a letter inviting her to audition for the band when she first arrived on campus.

“She was so excited. But we all said to her, ‘We don’t think they take women. They must have been confused by your name.’ But she was convinced they wanted her. So she went to try out and was told ‘We don’t allow women in the band.’ When she came back to the room, she was in tears. She was devasted.”

Dressing Up

Dress codes weren’t dissolved on campus until the end of the 1960s. Before that, pantyhose were required for women attending Sunday sit-down dinners and jeans and Bermuda shorts were allowed only on weekends.

Ken Graham, ’57, JD’62, remembers men also bristling at dress requirements in some cases—and leaning into them in other cases when he lived in West Quad.

“In the dining room on the second floor, the men were constantly trying to get around the requirement that you had to wear a coat and tie for dinner by such stunts as wearing a lab coat and a shoestring around their neck,” he recalls. “But on the ground floor where the women ate, we did not have any of this nonsense. A lot of men did start wearing suits to dinner.”