This year marks the centennial of the founding of the U-M Stephen M. Ross School of Business. Originally opening its doors as the U-M School of Business Administration in 1924, the institution’s leaders set out to pioneer the scientific study of business theory, administration, marketing, and more fields. In honor of the occasion, Michigan Alum shares this chronicle of the school’s founding, provided by the school itself.

This article was originally published in January by Michigan Ross. It has been edited for length. For more information and stories, visit the school’s 100 Years of Impact page.

While serving as U-M’s president from 1871-1909, James B. Angell, HLLD1912, led massive population growth among students (enrollment grew from around 1,100 to 5,000) and faculty (35 to 250). He favored new ways of thinking and scientific investigation, paving the way for schools dedicated to dentistry, pharmacy, nursing, music, architecture, and urban planning. Seeking to extend this scholarly mindset to the realm of business — at the time seen as more of a basic trade than a true profession like medicine or law — Angell promoted Henry C. Adams, a virtuous young professor, to chair the newly created economics department. Like Angell’s beliefs, Adams thought that economic behavior could be studied and regulated to improve wider society.

While Adams set out to “supply business talent of a superior order,” he had to contend with naysayers. He noted that “there is no typewriting, no stenography, no bookkeeping, no play at banking … those things are left where they belong in the commercial courses of the high schools and business colleges.”

The first classes became available in the fall of 1900. Soon, the course catalog included accounting, finance, wholesale and retail trade, statistics, railway organization and operation, and investment. Additionally, a marketing class was considered the first of its kind nationwide.

Adams’ economics courses gained traction with students throughout the early 1900s. Enrollment in the department of economics grew from 950 in 1914 to nearly 1,400 in 1919. Outside the classroom, the public started to view business administration as being on par with other elite professional pursuits.

In 1920, U-M, and the rest of the U.S., were rebounding from the throes of World War I. The University’s enrollment was on the rise, surpassing 10,000 for the first time in the 1920-21 academic year, and Marion Leroy Burton, HLLD1920, was in his first year as U-M’s president. Adams died in 1921 while he was still department chair, but Burton saw the promise of Adams’ work and ventured east for another visionary who could lead U-M forward in business education: Edmund E. Day, HLLD’45.

Day, who taught economics at Harvard University and Dartmouth College and was the chief statistician of the Central Bureau of Planning and Statistics in Washington, D.C., during WWI, became chair of U-M’s department of economics upon his arrival in 1923. He worked with Burton to quickly establish a formal business school. At the Dec. 21, 1923, Board of Regents meeting, Day presented his plan for the School of Business Administration. The school would award a master of business administration (MBA) degree upon successful completion of two years of study. Admission required three years of work in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, or equivalent elsewhere.

Day, like Adams, was focused on shaping business leaders who could build relationships between business and community. His focus was to use research and analysis to guide the curriculum, telling The Detroit News, “Ours is the task of making business scientists.”

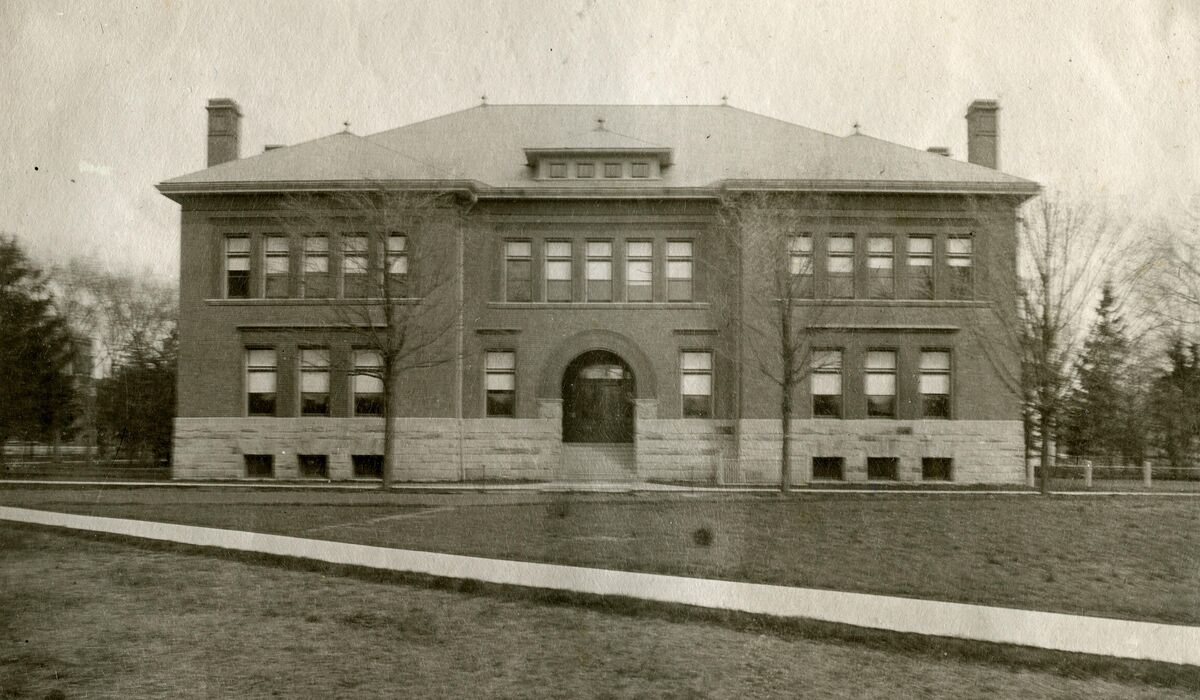

The U-M School of Business Administration opened its doors to students in September 1924, with Day serving as its first dean. Its first home was Tappan Hall, just west of the U-M president’s house on South University Avenue. There were 22 MBA students, 19 of whom completed the work for the year, and 14 faculty members.

Day’s vision of the school’s potential was evident in his first report to Burton: “Rapid development of the organization is necessary if it is to serve satisfactorily the student body, which it should attract in the immediate future.” Among other initiatives, Day cited the need for expanded faculty and facilities, a separate specialized library, and called for the establishment of a Bureau of Business Research to facilitate relationships more effectively between businesses and the school. The Bureau would open in October 1925.

“All of these needs must be met promptly if the school is to take its place among the ranking professional schools of Business Administration in this country,” concluded Day.

Ninety-nine years later, it’s safe to say that Dean Day’s year-one remarks were almost perfectly targeted in setting Michigan Ross up for a century of successfully training outstanding businesspeople.