From the mid-1800s until the late 1950s, large-scale dances, banquets, balls, and hops were the landmarks of many U-M students’ social calendars. The practice began in the 1860s with the Palladium — U-M’s original nine fraternities — organizing a big mid-year Society Hop at available area venues. The junior class was tasked with the tactical details, thus giving rise to the Junior Hop name. Though juniors were not always in charge, the “J-Hop” moniker persisted.

The dynamic and nature of the event began to change in the 1890s, however, when a larger, on-campus venue became available: Waterman Gymnasium (formerly located where the Dow Laboratory now stands). Later, the ballroom of the Michigan Union and the Intramural Building would become common options.

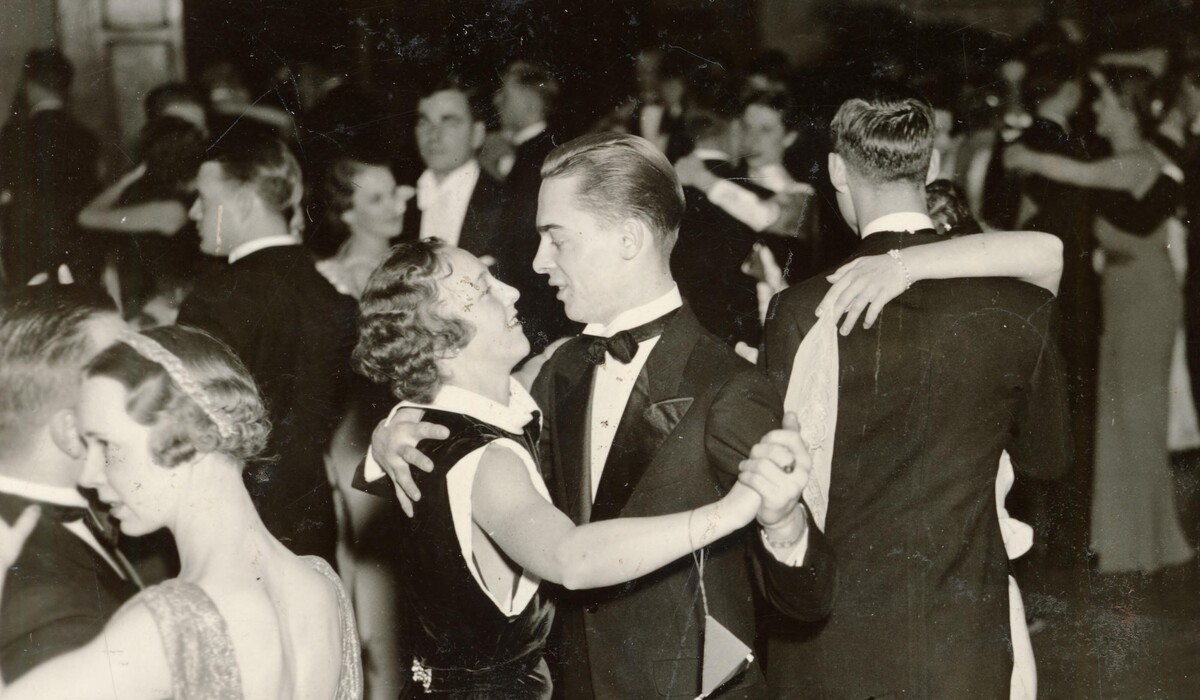

With the larger space and ever-growing student population, J-Hop’s scope and notoriety began to grow. What was once a one-night affair evolved into an entire weekend of satellite parties, customs, thematic decoration, and fashion.

Other dances sprang up as well, such as the Freshman Frolic, Soph Prom, and Senior Ball; college-specific events like the Architects Ball; and the Panhellenic Ball.

Whatever the year, though, dances being held on University property came with University oversight and approval. The J-Hop served as both a night of celebration and a gem in U-M’s public image, if not an outright attraction for prospective students. J-Hop was large enough for thousands to vie for tickets every year, and for iconic musicians to perform, including Duke Ellington and Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey.

Naturally, the oversight came with rough spots over the decades. Jazz and swinging big band acts took over from more formal orchestral music. The dances changed accordingly, going from the likes of the waltz to the more sensual tango. The generational headbutting was inevitable, with chaperones admonishing attendees or sitting them down. A few short-lived bans were implemented for fear of the University’s image.

But J-Hop and other dances persisted through the Great Depression, world wars, and other world events.

What these dances couldn’t withstand were twin factors: the University’s exponentially growing student population and the changing times. More and more students were attending U-M every year, and they were being given more options for a social life as the University expanded (including the addition of the Dearborn and Flint campuses) and the city of Ann Arbor developed.

The other factor was the prevailing attitude shift as students came of age in the late 1950s and into the 1960s. They were growing more aware of economic and civil injustices, more aware of world events like the Vietnam War, and more wary of establishment traditions like J-Hop.

A 1959 Michigan Daily editorial, ruminating broadly on how contemporary students navigate ever-shifting social group cues, piled on the J-Hop as being “so OUT even the OUT people won’t touch it.”

Attendance of J-Hop cratered after 1955, down to the mere hundreds by 1960. On May 11, 1960, the members of the Student Government Council voted 9-7 to not put J-Hop on the 1961 calendar, marking its end.

For more information on J-Hop, read “J-Hop’s Rise and Fall” by James Tobin for the U-M Heritage Project.

Gregory Lucas-Myers, ’10, is the senior associate editor of Michigan Alum.