On any given home-game Saturday in fall, the press box at Michigan Stadium attracts big personalities. Locally and nationally prominent journalists mingle and observe the play on the field, great pro athletes pop in to hobnob, and beloved former coaches stop by to offer analysis.

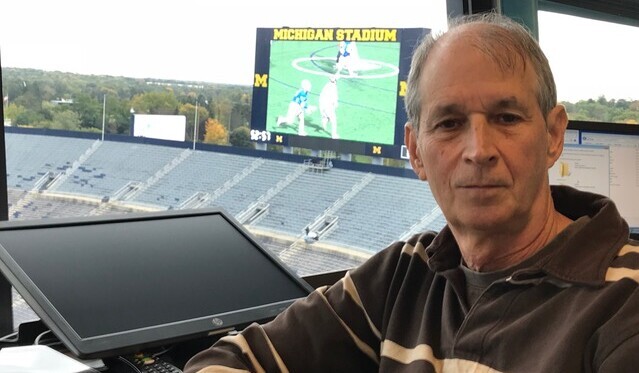

So even though he has sat up there for 252 home games as the 2022 season kicks off, it’s easy to overlook a bookish computer programmer behind his console who revolutionized how sports statistics are tabulated and reported.

But Jim Meyer, ’73, doesn’t mind.

The 72-year-old software engineer has been a deliberately quiet presence at the Big House since 1984 when he may have been the first to use a computer to collect the official data from a live college football game on behalf of a team. That season opener was notable at the time as a clash between future NFL quarterbacks Bernie Kosar of the University of Miami and, in his first start for the Wolverines, a sophomore named Jim Harbaugh.

Little noticed at the time — and largely undocumented by media ever since — was the fact that Meyer and his spotter, local lawyer Dan Landman, ’80, used a Texas Instruments personal computer running on MS-DOS and writing on 5.25-inch floppy disks to record the rushing and passing yardage, interceptions, sacks, fumbles, touchdowns, and more metrics unfolding in that 22-14 Michigan win.

“I can’t prove it, but I think that was the first [football] game of any level, college or pro, that was done on a computer,” Meyer says. “I think so. I don’t know of any other.”

His boss at the time, now-retired U-M sports information director Bruce Madej, agrees the moment was a turning point.

“We were the first ones to have statistics done by computer in the NCAA Division I that I know of,” he says. “A few years later, there were all sorts of companies doing it.”

A New Way

It may be difficult to imagine now, but until Meyer wrote his software, the standard stats for all college sports were taken down by hand by a team that often required more than six people.

“People sat there with these grids and filled in numbers and add them up as they went,” Meyer recalls. “I had this idea. I called up the athletic department and sports information department specifically and I said, ‘Is anybody doing this on a computer? And would you have any interest?’”

Madej had an early version of a computer stat program given to him when he took over the director position, but the computer stats took more time to enter than doing it by hand. He quickly deep-sixed that program. After that, would-be computer tinkerers would walk into the office with their plans. He always replied: “Go back and find a way to have the play-by-play entered to create the official stats for the game.”

“Jim [Meyer] walks into my office and he says, ‘Well, here it is,’” Madej says. “And I go, ‘Here’s what?’ I had told so many people that I needed this and nobody came back; I couldn’t even remember Jim coming in the first time.

“I said, ‘Wow, this data is good.’ I said, ‘OK, we’re gonna blow holes in this.’ And we did. I gave it to my stats guru, Jim Schneider, and we blew all the holes in it. We said, ‘If you can fix this, we’ll use it.’ Of course, I never thought he could do it because nobody could.

“Next thing I know, he walks back in, and he says, ‘Here it is again.’ We just had to clean it up a little and we started to use it. And it was amazing.”

Meyer and Landman — whom Madej knew through his brother, Larry, ’82, a student assistant in the sports information department — did a successful trial run at the spring intra-squad game and received the green light to “unofficially” start with the home opener against Miami in September. They were given full approval to join the U-M stat crew later in the season.

Getting In The Game

At the time, Meyer was 11 years out of his U-M undergrad life, living in Ann Arbor, and working first as an auto exhaust systems engineer and then for a bicycle accessory manufacturer. He was a self-taught freelance computer programmer and die-hard football fan with season tickets.

“I wasn’t a great athlete, so this is a way to be involved, to contribute, to watch a game and be somewhat of a participant,” he says. “I couldn’t run fast enough or jump high enough, but I could do this. I am a geek who likes sports, so I married the two. It was kind of a logical thing for me.”

As a software challenge, Meyer says, scoring a football game wasn’t that difficult. He had to program the computer to keep track of where the ball was on the field starting with the coin toss and kickoff, and then it was largely a matter of relying on Landman to watch through binoculars and report the numbers of players involved in downs and what happened. Some of the trickier elements of football — how to teach a computer to understand a play in which a first down is erased by a penalty or keeping track of players of the same team who use duplicate numbers — presented complications. He figured those out, too.

“When we started in ’84, it was purely experimental,” Landman says. “We didn’t know how the software was going to react or how the computer was going to react if there had been bad weather or power failure or something along that line. We were sort of in uncharted territory. The fact is that Jim wrote a phenomenal program. Halfway through that season, we were the official stat crew. The group that had been doing it by hand had done it for years and years and years, probably going back to the ’60s and maybe even the ’50s.”

Quick, Accurate Stats

To Madej, computerized data was gold.

With instant, computerized tabulations, he could give the coaches and journalists statistics on the game significantly faster. A dot-matrix printer in the locker room chugged out stats at halftime, which was a revolution.

“He’s made me look real good,” Madej says. “You want to be able to tell as many stories as accurately and quickly as you can do it. That is what Jim’s material was able to do for us.”

Despite Madej’s urging, Meyer never sold the software he wrote to track football, and later basketball, games. He did eventually sell software tracking ice hockey to other schools. Meyer customized his program to U-M’s needs, and it was used into the late 1990s, but he never profited in any serious way from the work he pioneered.

“There’s a huge difference between writing software for yourself and writing it for commercial use,” says Meyer, who co-founded a software company in 1989 that wrote unrelated programs. “If you write it for commercial use and anybody can use it, it’s got to be a lot more robust and a lot more error-proof and much more intuitive. You write it for yourself, you can skirt some of that. I don’t have to have a user manual. I don’t have to do training.”

In the early days, the crew that took down stats by hand continued to do so as a backup system, but Landman and Meyer quickly developed ways to prevent errors.

TV monitors in the press box were on a slight delay from the live action, so Landman could look up to see the play from a TV angle if there was ambiguity. Eventually, they would have the ability to rewind the video on their own monitors to check. As the NCAA charged the home team with gathering the official stats, occasionally the opponent would request modest fixes — a tackle attributed to a different player or a missed rushing yard here or there — in the days after the game.

But Meyer says Landman’s impressive accuracy has been key to their success.

“He was critical, because if I don’t get the right information, and if I have somebody there that’s giving me the wrong numbers and the wrong yardage or they get flustered or behind or confused, I’m screwed, the whole thing falls apart,” Meyer says. “Dan was and is superb.”

Every Saturday

Nearly 40 years later, Meyer hasn’t skipped a home football game even he’s what he calls “emeritus” status now, mostly serving as an advisor and accuracy-checker in the process. He’s married and spends most winters at his home in Costa Rica.

He’s rubbed shoulders for decades with football and journalistic royalty, but they never paid him much mind.

“It was a little surrealistic for me having been a fan, having sat in the fans’ stands for years, that here’s Joe Falls sitting in front of me. Brent Musburger walks by. There’s Lynn Swann. It’s pretty interesting,” Meyer says. “I’ve met Harbaugh a couple of times — the first time as a player in Bruce’s office. I’m sure he doesn’t even remember. Some of the coaches that have retired I kinda know, because they’ll be up in the press box. And that’s fine. We don’t want to get pressured. We have to be totally unbiased.”

As dispassionately as they try to watch the games to protect the integrity of the data, Meyer and Landman do have moments when they remember they’re U-M fans.

One such time came in September 1994 with the “Miracle at Michigan.” University of Colorado Buffaloes quarterback Kordell Stewart chucked a 64-yard Hail Mary pass, with time expiring, that was caught to win the game 27-26.

“We sat there looking at ourselves like, ‘What the hell just happened?’” Landman says. “But then, of course, we had to jump into stat mode and figure out how many yards the play was and so forth, figure out if there was going to be an extra point or not.”

STEVE FRIESS is a Michigan-based contributor to Newsweek and a 2011-12 Knight-Wallace Fellow at U-M.