For the Good of the Community

•

Head photo courtesy of Jeremy Moghtader

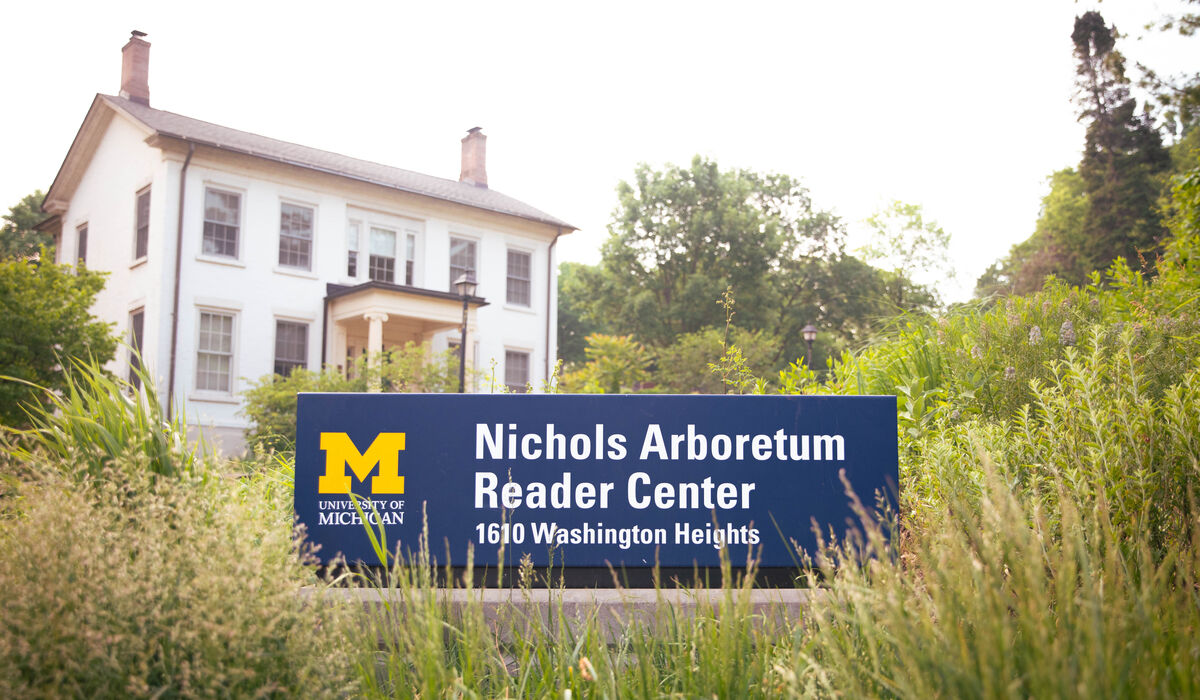

Many people know the Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum simply for the peony garden and indoor conservatory. But Anthony Kolenic, the director of the beloved space, says that’s like seeing a big, beautiful house and only marveling at the front door.

Kolenic is proud that the space is known for its undeniable beauty, drawing in more than 525,000 visitors every year — the most-visited University of Michigan entity besides the hospital and football stadium.

The botanical gardens boast an indoor conservatory, outdoor gardens, and three miles of trails. The Nichols Arboretum’s famous peony garden blooms in May, but trails and outdoor collections keep the space bustling year-round. However, the Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum (MBGNA) also encompasses the Horner-McLaughlin Woods, a 90-acre sanctuary site preserving native plants and wildflowers; the Mud Lake Bog, a 260-acre research site of diverse ecosystems; and Campus Farm, a student-driven farm promoting carbon neutrality, sustainable food systems, and diversity, equity, inclusivity, and justice (DEIJ) initiatives.

“A lot of people’s initial knowledge of the space is through the beautiful things that are on the properties that are managed here,” says Jeremy Moghtader, ’98, MS’04, the Campus Farm program manager. “But in addition to all of that aesthetic beauty, I think there’s a lot of deep and rich, thought-provoking interactions that people can have that help them understand the relationships between humans and society and nature and how to navigate our relationships to those things and each other in ways that are sustainable and just and — in the case of the farm — hopefully, delicious.”

Kolenic says that the gardens and the arboretum are “place-based, but not place-bound,” meaning they aren’t confined to their physical spaces and are positioned to use the land for wider impact. So when MBGNA underwent a strategic planning process in 2021, Kolenic used key questions (such as: “Within a university context, where and how can MBGNA yield — not wield — power toward decolonial and co-liberatory action?”) to develop goals that utilize their physical structures, land, and other spaces for restorative justice.

Backed by a profound sense of responsibility and a unique position between the University and community, programs and initiatives facilitated through MBGNA are leveraging land and spaces for community good.

Urban Agriculture Resilience Program

Among the growing programs within MBGNA is an internship program through Campus Farm.

Started in 2017, the Urban Agriculture Resilience Program tapped U-M students to intern at D-Town Farm in Detroit to learn hands-on about urban agriculture and food systems.

Now, Campus Farm co-leads the internship with four farms in southeast Michigan: Cadillac Urban Gardens, Oakland Avenue Urban Farm, Growing Hope, and Detroit Black Community Food Sovereignty Network’s D-Town Farm. The program funds three interns a year who rotate through the four partner farms during their internship period, which lasts more than three months during the summer term.

Campus Farm facilitates coordination of the program, including processing applications and providing the funding that pays the students for their work. But everything they learn happens on the farms.

“When you’re on-site with those farms, you are there to do what they need doing,” Moghtader explains. “It might be weeding. It might be running to set up a pop-up market. It might be digging a ditch — literally.” But this hands-on experience shows students the work that needs to be done to make all the farms accomplish possible.

And these are not massive, industrial farms — they’re organizations dedicated to community development, food security, and food sovereignty. Cadillac Urban Gardens (co-founded by alum Sarah Clark, MUP’15) provides culturally relevant produce for free to Detroit residents. Growing Hope in Ypsilanti supports food entrepreneurs with free workshops, an Incubator Kitchen, and community connections.

“We have students working in collaboration with us, with community members, to go out and do hands-on, real-world things in a way that isn’t just about the student learning but is also about community-led and community-driven effort and impact. In that way, everybody wins: students get experiences that are directed by the organizations that utilize their assistance,” Moghtader says.

The internship is only half of the program, however. Campus Farm also grows seedlings for some partners, utilizing greenhouse space to grow transplants.

“They are little seeds that sprout and build resiliency here with us before they’re taken to farms in Detroit and across southeast Michigan that are doing the good work in their own communities and neighborhoods. … We think of ourselves as a silent partner in that way,” Kolenic says.

Some partner farms don’t have the expensive infrastructure or greenhouse space to get a head-start on planting season, so approximately 14,000 plants build resiliency at U-M before being transplanted to partner farms in the spring. Campus Farm often provides specific starts they know the farms need, but also offers leftover plants from the annual plant sale that would otherwise end up being composted.

“I think the beauty of it and why it works so well is that it’s relationship-based. What we do together grew organically out of those relationships and us thinking about how we can do this in a way together that is synergistic and powerful,” Moghtader says.

Refugee Agricultural Partnership Program

Refugees are learning local farming practices, engaging in professional development, and connecting to the land at MBGNA.

Through a partnership with Jewish Family Services in Ann Arbor and funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, participants attend small classes where they learn about the seasons, soil, and water in Michigan and use community garden-style plots to grow local or culturally relevant seedlings, find community, and learn entrepreneurial skills they can use to begin a career in local food production.

The Refugee Agricultural Partnership Program began in 2022 and hosted three cohorts last year and will host two this year, with the first cohort already underway for Michigan’s first planting season. The participants come from all over the world including Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, El Salvador, Syria, and more.

Kolenic says the program is a land-based community development and humanitarian services platform, but it’s also much more than that for the participants.

“People who have been ripped from their homelands and are now part of this community can gain a sense of place and relationship to the land. That is inherently healing. We’re just trying to make something that can be dehumanizing more human,” he says.

The program lasts about eight weeks and participants have transportation and access to the 20,000-square-foot space whenever they need. There are about 75 plots in the space, so participants can continue to use them throughout the summer or even into a second year if needed. Though participants can’t currently sell what they grow in the Freedom Garden, Jewish Family Services may one day be able to secure land to support small business growth.

For now, the land, programming, and community support provide a starting point for refugees to find stability and a new connection to the land thousands of miles from home.

Heritage Seeds and the Indigenous Collaborative Garden

MBGNA is aiming to reunite important seeds with their original Indigenous owners. More than 3,000 seed lots (a labeled batch of seeds, often collected from a specific place) rest at the U-M Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, though it’s been decades since they’ve been intensely studied. All were collected from tribal growers, including a relatively small set from Anishinaabec nations in Michigan and Ontario, Canada.

“It’s our call to be good stewards. That also means helping the tribal colleagues, who have been displaced from here, find which of their relationships are still here, whether it’s seeds in a museum, botanicals in a museum, [or] native plants on the ground,” says David Michener, a MBGNA curator.

The effort, the Heritage Seeds project, was funded by the Graham Sustainability Institute.

“It’s no living person’s fault, but it is our responsibility to reunite those seeds with their peoples,” Kolenic says.

The seeds are living things, and U-M’s general counsel worked with the Michigan Anishinaabek Cultural Preservation and Repatriation Alliance, which represents all 14 tribes in Michigan, to establish a renewable agreement that frames the way U-M and the tribes can work together.

As the legal agreement was being established, MBGNA began the Indigenous Collaborative Garden with tribal partners to demonstrate how tribal communities and University leaders could work together despite historical challenges. Different selections of corn or a Three Sisters Garden (comprised of corn, beans, and squash) are grown in a secure space to ensure physical safety from animals and virtually eliminate the potential genetic contamination through cross-pollination.

One set of seeds has come out of the museum as part of the Heritage Seeds project, but they aren’t being grown on U-M land.

“The community decided that they wanted the seeds to ‘taste the soil of home’ for their homecoming rather than be grown here. And that’s the community’s decision,” Michener says.

Accessibility

With many buildings established decades before accessibility became a priority, some spaces at MBGNA are due for accessibility upgrades. But Kolenic wants to ensure MBGNA isn’t just thinking about accessibility in terms of compliance.

“[It’s about] making really positive experiences for all ways of being in the world, regardless of one’s body or cognitive development, or gender or ethnicity, all of which can be understood as forms of accessibility,” he says.

MBGNA has partnered with a student group at the School for Environment and Sustainability to survey the arboretum’s slopes and material choices and make recommendations on how to alter them. But accessibility for rustic, outdoor spaces like the arboretum also includes setting accurate expectations for visitors. They plan to update trail wayfinding signage and mechanisms, based on tools developed by the local disability community.

“Utilizing the tools that are emerging out of disability studies, occupational therapy, activist organizations, and our local tri-county disability network is the way to address, over time, those inherited ableist spaces and systems,” Kolenic says.

Some trails may not be able to be adapted for mobility devices but visitors can reserve a trail chair — a hybrid between a wheelchair and a mountain bike that can traverse uneven and hilly terrain — and they can still be made more accessible for people with vision or hearing impairments. Soon, there will be quieter, sensory-friendly hours available for visitors too.

In Bloom

MBGNA’s commitments to equity, justice, and biocultural diversity; research, teaching, and experience-making; and organizational evolution will continue to blossom over the next several years.

Kolenic hopes that MBGNA’s unique position between the University and the community not only promotes a deeper connection between the two, but opens up a unique “third space” where the barrier between University and community is at its lowest.

“An organization like ours, with assets that drive relationships with and through the natural world at a time that is most urgent, has to open that third space to create a better and new relationship between universities and their publics,” Kolenic says. “Land is a tool to do that.”

Katherine Fiorillo is the editor of Michigan Alum.