The University of Michigan may have put the city of Ann Arbor on the map, but its origins are in Detroit, the city that put the world on wheels.

In 1817, Detroit was the territorial capital, but it was still a long way from being a bustling metropolis or fount of knowledge. Indeed, of the 1,200 or so people who called Detroit home at the time, most were old French settlers more interested in catching beavers than catching up on their Plato. Few of them could even read.

Nevertheless, four Detroit luminaries decided to give it the old college try and attempted to carve an institution of higher learning out of the wilderness. On Aug. 26, 1817, the Territorial Legislature of Michigan passed an act authorizing the school’s creation.

One of the men who inked that founding document was William Woodbridge, secretary of the Michigan Territory and acting governor. A big proponent of public education and the pursuit of knowledge, he would go on to become the state’s second governor.

Another was Augustus Brevoort Woodward, best known today for the avenue bearing his name, but at the time he was known as dominant figure in Detroit politics. Woodward was the presiding judge of the Supreme Court of the Michigan Territory, sent to Detroit by President Thomas Jefferson in 1805 to help whip Michigan into shape for statehood. He arrived shortly after a fire had leveled Detroit and dedicated himself to planning and rebuilding the village. Woodward would be the driving force behind the creation of what would later become U-M.

Now, Woodward was a tad overzealous in his passion for classical learning. In fact, he believed the English language didn’t do justice to defining the classifications of human knowledge—so he coined words of his own. “University” didn’t quite cut it, so the school was christened the “Catholepistemiad,” or “University of Michigania.” His professors? They would be “didactors,” teaching “didaxum,” not “subjects.”

Likewise, the Catholepistemiad’s 13 areas of study also would take on Greek-flavored names:

• Catholepistemia (universal science)

• Anthropoglossica (“embracing all the epistemum or sciences relative to language” and literature)

• Mathematica (mathematics)

• Physiognostica (natural history)

• Physiosophica (natural philosophy)

• Astronomia (astronomy)

• Chymia (chemistry)

• Iatuca (medical science)

• Æconomia (economics)

• Ethica (ethics)

• Polemitactica (military science)

• Degitica (historical sciences)

• Ennœica (intellectual sciences, including religion and psychology)

Woodward’s intent was likely to emphasize the importance placed upon the classical tradition at the Catholepistemiad, but his extravagant coining of words likely didn’t play well with Detroit’s fur trappers.

Indeed, “there was an intense distrust throughout Michigan of the institution,” the Rev. Andrew Ten Brook wrote in 1895, recalling the University’s first years. Ten Brook, one of U-M’s first faculty members and librarians, continued: “Most of the religious people had no confidence in its management by the state. A much larger class … feared that the university would merely nourish an intellectual aristocracy.”

Woodward’s contrived verbiage also didn’t sit well with Lewis Cass, Michigan’s territorial governor from 1813 to 1831. Woodward had given the school “such a pedantic and uncouth name,” Cass said, “we always refused to adopt it and called it the ‘College of Detroit.’” Most accounts indicate that nobody, save for Woodward, ever used the fantastical lingo.

The “education for all” belief was coupled with the University being one of the country’s first educational institutions to be paid for by public, not private, money.

But amid all of the talk of “didaxia” and “instructixes” was some pretty game-changing stuff. The act said that if you lived in Michigan and wanted to attend the University, you could, even if you were unable to afford the tuition. This “education for all” belief was coupled with the University being one of the country’s first educational institutions to be paid for by public, not private, money. To pay for it, taxes were hiked 15 percent, all of which was earmarked for the Catholepistemiad.

On Sept. 8, 1817, the University was organized by divvying all 13 of Woodward’s professorships between U-M’s other two founding fathers: Father Gabriel Richard and the Rev. John Monteith.

Monteith, a 29-year-old Scotch Presbyterian minister who formed the first Protestant Society in Michigan, became the Catholepistemiad’s first president. Richard, a refugee of the French Revolution who had come to the city nearly two decades earlier, would serve as vice president. The priest of Ste. Anne’s Catholic Church had run schools for Native Americans and long championed the creation of a university in Michigan.

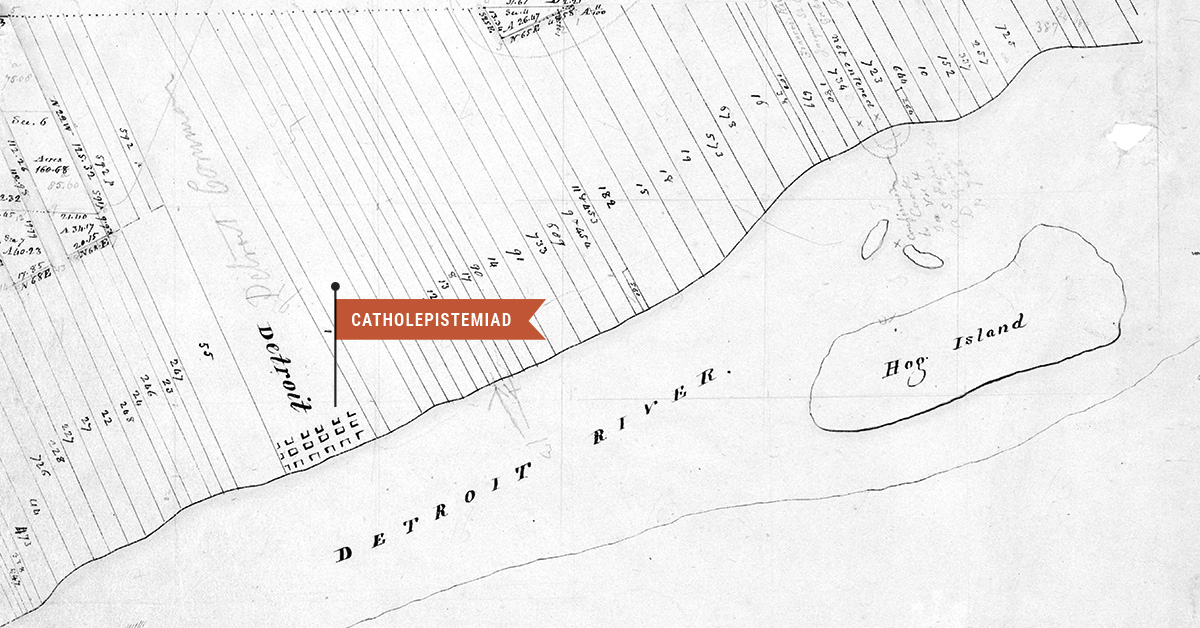

On Sept. 24 of that year, Woodward led the cornerstone-laying ceremony for the University’s home on the west side of Bates Street, near Congress Avenue, in what is now the heart of downtown Detroit. It was a small, two-story building, 24 feet by 50 feet. It more closely resembled an old schoolhouse than any current U-M building.

Though the Catholepistemiad was the forerunner of the University of Michigan, it never hosted a collegiate-level class in Detroit. That’s because it soon became apparent that what Detroit needed was not a university with subjects no one could pronounce, but “common schools,” similar to high schools. One of its instructors later wrote that there were likely only “13 or 14 liberally educated men” in the entire town when the school opened. Two departments were quickly established to bring Detroiters up to speed: The Classical Academy opened in rented space inside a private residence in February 1818 (the Catholepistemiad’s building was still under construction), and the Primary School followed that August. It was a democratic place, with the children of Gen. Alexander Macomb and Cass seated next to those of tradesmen and shop owners.

On April 30, 1821, the original charter was amended and the school reorganized. Woodward’s archaic language was ditched in favor of plain English, and the Catholepistemiad gave way to the University of Michigan. A board of trustees would now govern the University.

On March 18, 1837, the state gave the University permission to leave Detroit and take Ann Arbor up on its offer for free land. Those first 40 acres in Ann Arbor were bounded by State Street and North, South, and East University avenues. U-M’s first classes there were held in 1841; six freshmen and one sophomore were instructed by two professors.

The old Catholepistemiad building was torn down in 1858. Today, a state historical marker is placed near its original location, 44 miles and many years removed from the University’s humble beginnings.

Dan Austin is the author of three books on Detroit history and runs the online architectural resource HistoricDetroit.org. He is a former reporter, columnist, and editor at the Detroit Free Press and Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan’s former deputy communications director.