Feed People, Not Landfills

•

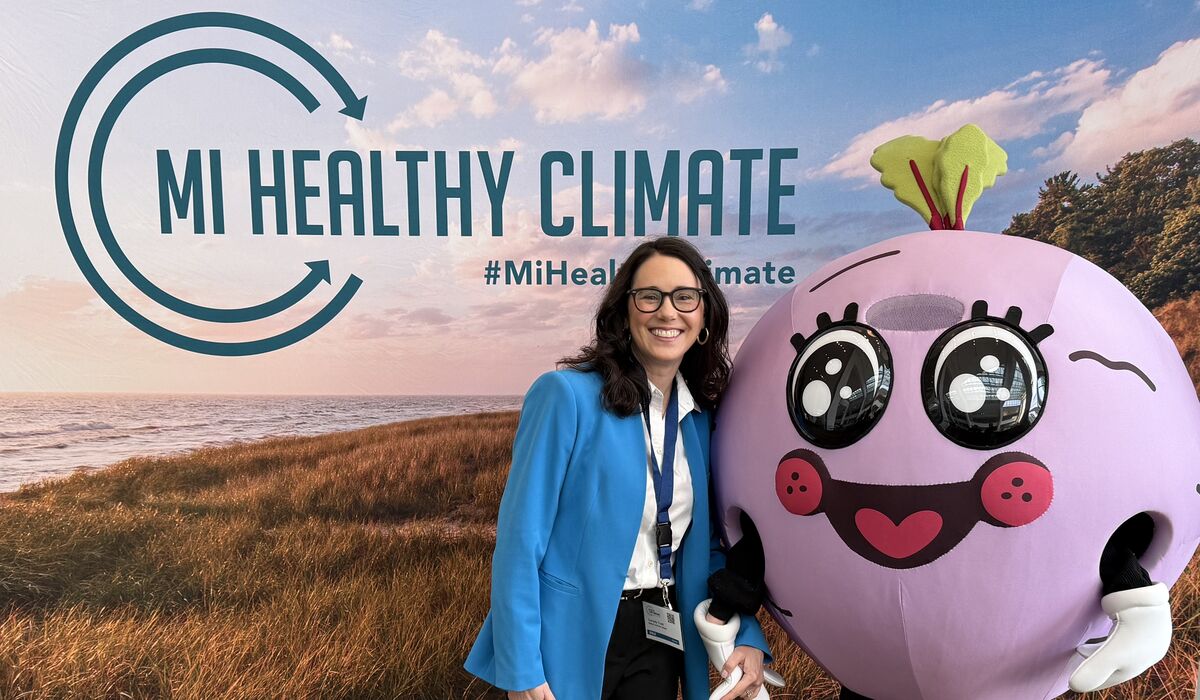

Photos courtesy of Make Food Not Waste

Propped against the back wall of Danielle Todd’s, ’94, home office is the new costume for Make Food Not Waste’s grinning spokes-vegetable, Sweet Beet. “We’re dealing with some really heavy issues of climate change and food insecurity, but we all have fun doing it,” Todd says, acknowledging the smiling purple beet mascot visible behind her. “People want to be part of what we’re doing because it is joyful. We’re not lecturing people; we’re not wagging our fingers at them. We’re not doom and gloom.”

Todd is the founder and executive director of Make Food Not Waste (MFNW), a Detroit-based nonprofit applying long-term solutions to Michigan’s food waste problem. Thousands of partners and volunteers have embraced MFNW’s approach even as stats about food waste raise alarms. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), food waste accounts for 58 percent of methane emissions from municipal landfills in the U.S., contributing to accelerated global warming.

“There is a direct relationship between landfilled food and a hotter planet,” a MFNW document notes. “Because we landfill more than 2 billion pounds of food every year in Michigan, we unnecessarily pump billions of pounds of methane into the atmosphere that in turn traps heat and brings extreme weather, wildfires, and polluted air.”

Methane Moonshot

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and EPA announced the United States’ first-ever food loss and waste reduction goal, calling for a 50 percent reduction in food waste to landfills by 2030. Instead of 328 pounds of food wasted per person, just five years from now each American should produce approximately 164 pounds a year.

MFNW and partners published the Michigan Food System Waste Reduction Roadmap which offers strategies for the state of Michigan to get there. Food waste annually creates an estimated 11.1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions and $11.9 billion in lost revenue across Michigan, more waste per capita than any other state.

Zoom out on the map and the issue remains. A study published in January by the University of California, Davis found that the U.S. still generates almost exactly what was being produced when the reduction goal was announced in 2015.

Todd sees findings like these and suggests that the best course of action is, well, action.

“There are many ways to make a difference for the environment, but food waste reduction is something we can all be a part of, and achieved relatively easily, inexpensively, and quickly,” Todd says.

MFNW board president Matthew Naud, MS’85, MPP’90, says bold solutions are needed.

“We need to think different and big and kind of in a very non-traditional way if we’re going to do this in the next five years, and that’s what Make Food Not Waste is doing.”

Prevention

Naud said one of MFNW’s slogans is “feed people, not landfills” because preventing food waste altogether by eating food is more effective than partial solutions like recycling and composting. Two of the organization’s core initiatives for doing so are Upcycling Kitchens and Every Bit Counts.

Located in areas with noted food insecurity, skilled chefs transform edible food scraps into nutritious meals for anyone who wants one through Upcycling Kitchens. Since the first kitchen opened in January 2021, MFNW chefs have made 250,000 meals, and kept roughly 300,000 pounds of food out of landfills.

Dishes served include herb-roasted turkey using surplus meat from Kroger, a vegan curry vegetable stew and rice pilaf using vegetables from Metro Food Rescue, and a fruit cobbler made with leftover dough from Detroit’s Eastern Market’s Pietrzyk Pierogi.

“We always want people to look at the food and say, ‘oh my, I can’t believe that was going to be thrown away,’ which is wonderful, but the kitchens are a short-term response to the fact that food is going to waste,” Todd says. “It’s never going to solve the problem permanently; you also need initiatives like Every Bit Counts.”

In Every Bit Counts, MFNW coordinates with partners across sectors to combat food waste in the 15 most populated cities in the state. It starts in Southfield, Michigan, where an estimated 15,000 tons of food is wasted annually. The plan estimates an average four-person household in the city could save $2,500 per year if all edible food was eaten rather than discarded.

“Reducing food waste saves families money, and that money is invested in the local economy. It’s economic development,” Naud says.

Changing Culture

Todd says that food waste is a cultural issue in the U.S., and MFNW is embedding itself in cities across Michigan to change that culture. She credits her U-M education with helping her believe social change is possible.

“I have always believed you could influence people for good, and I never really found a way to do that until starting Make Food Not Waste,” Todd says. “A lot of our work goes back to what I learned in psychology at U-M in terms of the power of influence, how to use peer pressure for good, and how to change cultural norms.”

One way MFNW is influencing people’s ideas about food waste is social media, with cooking tips and demos on TikTok and Instagram.

@makefooddetroit Did you know there’s a better way to cut a bell pepper? 🫑✨ A simple technique can help you get the most out of your produce, reduce food waste, and even save money in the long run. By cutting smarter, you’re making sure every piece serves a purpose—because why let any of it go to waste? Small changes in how we prep our food can make a big difference, and this method is all about maximizing what you have. More pepper on your plate, less in the trash! 🌱♻️ Watch and learn, then try it yourself! #makefoodnotwaste ♬ Little fresh love - I like you rabbit much - 福林斯通

“Did you know there’s a better way to cut a bell pepper?” a recent caption on a MFNW TikTok video asked. “A simple technique can help you get the most out of your produce, reduce food waste, and even save money in the long run. By cutting smarter, you’re making sure every piece serves a purpose — because why let any of it go to waste?”

Todd said both education and motivation are essential ingredients to the recipe of reducing food waste.

“Education is the start, but research shows people who know that food waste is a problem, do not behave any differently than people who do,” Todd says. “You must be inspired. Maybe you see these videos and think about trying to reduce waste at home, but need more information, support, and motivation. That’s where we come in.”

Steve Zoski, ’13, is a freelance writer based in Dearborn, Michigan.